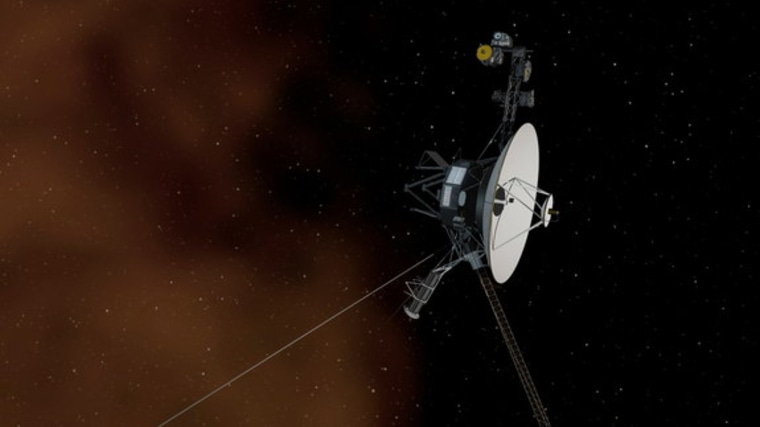

Thanks to NASA's far-flung Voyager 1 spacecraft, now exploring the final frontier beyond our solar system, humanity can tune into the sounds of interstellar space.

Scientists announced Thursday that Voyager 1 left the solar system in August 2012 after 35 years of spaceflight, making it the first craft ever to reach interstellar space. No other man-made object has ever traveled so far away from its home planet.

To mark the occasion, NASA unveiled the first Voyager 1 recording of the sound of interstellar space, offering the probe's strange, otherworldly take on its new frontier. The sounds are produced by the vibration of dense plasma, or ionized gas; they were captured by the probe's plasma wave instrument, NASA officials wrote in a video description. [Voyager 1's Journey to Interstellar Space: A Photo Tour]

"When you hear this recording, please recognize that this is an historic event. It's the first time that we've ever made a recording of sounds in interstellar space," Don Gurnett, principle investigator for the Voyager plasma wave investigation, said in a news conference.

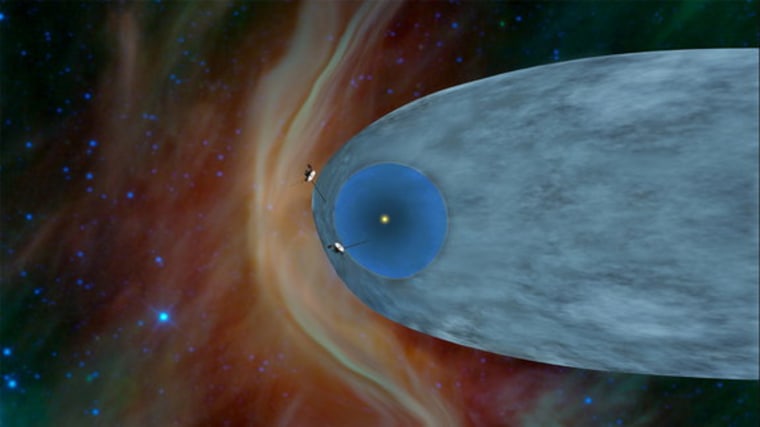

Researchers used the plasma data to infer that Voyager 1 first came into contact with the interstellar medium, effectively taking humanity between the stars, on or around Aug. 25, 2012.

"There were two times the instrument heard these vibrations: October to November 2012 and April to May 2013," NASA officials wrote. "Scientists noticed that each occurrence involved a rising tone. The dashed line indicates that the rising tones follow the same slope. This means a continuously increasing density."

Voyager 1's plasma sensor broke in 1980, so scientists had to get creative, and a little lucky, to figure this out. A massive solar eruption in March 2012 arrived at the location of Voyager 1 about 13 months later, making the plasma around the probe vibrate, NASA officials said.

That vibration helped researchers understand the density of the plasma, determining that it was 40 times more dense than measurements taken in the outer layer of the heliosphere, the bubble of charged particles and magnetic fields that the sun puffs out around itself.

The observed density matched up very well with what researchers expected to find in interstellar space.

"Now that we have new, key data, we believe this is mankind's historic leap into interstellar space," Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist based at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. "The Voyager team needed time to analyze those observations and make sense of them. But we can now answer the question we've all been asking — 'Are we there yet?' Yes, we are."

Voyager 1 launched on Sept. 5, 1977, about two weeks after its twin Voyager 2. The two spacecraft made it through their "grand tour" of the solar system, taking close-up looks at the Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune systems. Their original mission ended in 1989, but the probes soldiered on, streaking through the unexplored regions at the outer reaches of the solar system.

The Voyager team still communicates with the two spacecraft every day, but the probes' extreme distances pose a challenge. At the speed of light, it takes about 17 hours for a message to reach Earth from Voyager 1, which is currently about 12 billion miles (19 billion kilometers) from the sun.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramerand Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

- Voyager 1 Records 'Sounds' From Interstellar Space | Video

- Voyager Welcomed To Interstellar Space | Video

- How the Voyager Space Probes Work (Infographic)

- Solar System Explored: Today's Deep-Space Spacecraft (Gallery)