Beyonce releases an album, with videos for every track, on a random midnight in December. Wu-Tang Clan announces there will be only one copy of their upcoming album. Thom Yorke releases his album on Bittorrent, eschewing, as he put it, that "cloud malarkey." What do all these have in common?

Simply that in an age when music has become a commodity, they stood out from the rest. It's a strange era for musicians, and many are realizing how the digitized world offers an unprecedented opportunity to forge new links with their fans.

But it isn't bottled lightning: Even for the biggest acts in the industry, an Internet-forward release strategy might not work, or could backfire completely.

"The music industry and entertainment as a whole has changed," Wu-Tang Clan executive producer Oliver "Power" Grant, who has brought the hip-hop group through two decades of success, explained in an email to NBC News. "Out with the old industry business models ... and in with the independent creativity of musicians, artists, creatives and techies."

For decades the general rule was: record, send out singles, promote a music video or two, then release the full album a month or two later. That worked pretty well for a long time, but the innovations of the Internet and smartphones were, as music self-publishing site Bandcamp's Andrew Jervis put it, explosive:

"Five years ago, the music industry blew up," he said in a phone interview. "And some of the pieces are still in the air."

If you didn't get hit by the flaming wreckage (as many brick and mortar music stores did), the resulting landscape is full of possibilities. Sure, smaller bands have more reach, getting fans across the world to listen to and buy their tracks on Bandcamp and Soundcloud. But the big artists have been affected even more.

"This is an industry that likes to shock and surprise and delight," said David Bakula, VP of Analytics at Nielsen. "We have no idea what's going to happen next. Tech is being built on the back of entertainment, and entertainment is benefiting from the advances in tech."

The gold, or rather, platinum standard for crazy release strategies is Beyonce's "surprise" album. After she recorded it and struck deals with Apple and Facebook in complete secrecy, it appeared with no warning last Dec. 13 — and sold 1.4 million copies in just four weeks, triple what her last album did.

The music industry was electrified by this phenomenal success, and other artists attempted to replicate it.

"Since the surprise album it's become almost a weekly guessing game," jokes Keith Caulfield, associate director of charts and sales at Billboard. "Who can top Beyonce?"

But, he continues: "Nothing is ever really going to be like Beyonce's thing. Not just anyone can do this."

A recent article by Nielsen shows this to be the truth; other A-list musicians, from Jay-Z to Skrillex, have tried various forms of dropping albums without warning. Via apps, bundled with popular phones, and by other means, all-digital rollouts have tried, and failed, to do what Queen Bey did.

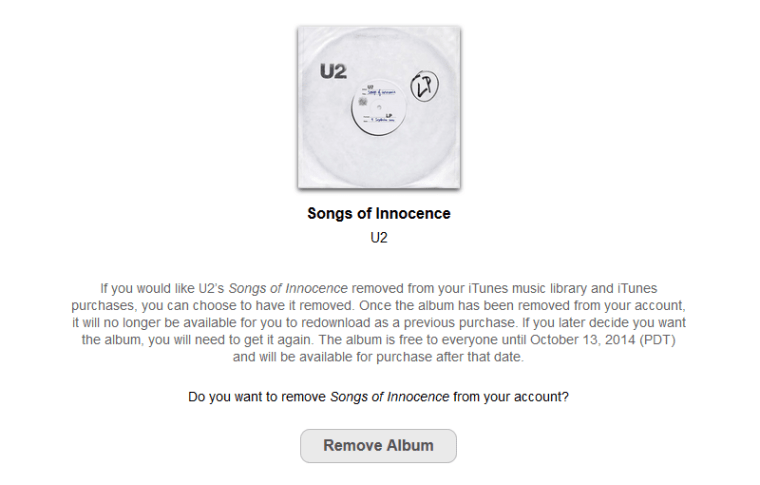

The biggest backfire had to be the now-infamous launch of U2's "Songs of Innocence." Apple and the band's plan to inject the album into every iTunes library in the world may have set records, and millions surely enjoyed the freebie, but enough consumers were put out at having the music forced on them that Apple had to issue a special U2 removal page.

The problem may have been a failure to really engage with the fan. Nowadays, Caulfield points out, "You can be on Twitter with Lady Gaga, and maybe she tweets you and it makes your life." That's an experience fans clamor for. Where's the "experience" in suddenly owning a record you perhaps never wanted?

Musicians and marketers should understand there's more to it than just putting the product out there, suggested Wu-Tang's Power: "It's a new way of thinking, with smartphones, Internet, apps, social media and such. The way consumers are experiencing, finding, getting and sharing music and content is different today as a result."

Artists, he said, are having to work harder to attract the notice of increasingly distracted consumers and find ways to retain shortened attention spans. Several recent musical events act as evidence.

Wu-Tang's own "Once Upon a Time in Shaolin" will exist only as a single copy, intended as a museum piece (their other new album, "A Better Tomorrow," is undergoing a more traditional release). This seemingly insane strategy electrified the Internet as people speculated on ways to get around the limitation, passed rumors of million-dollar bids for the record, and scrambled to catch up on the Wu-Tang discography. The least shareable album conceivable is an unqualified digital success — and no one outside the group has yet heard the finished product!

Thom Yorke, who has for years been critical of the industry's recording and distribution models, released his latest album using peer-to-peer file-sharing software Bittorrent, saying, "If it works well it could be an effective way of handing some control of Internet commerce back to the people who are creating the work." And boy did it work well: at this moment the album and its free single have seen 2.5 million downloads.

Electronic artist Boards of Canada, instead of simply announcing its 2013 album "Tomorrow's Harvest," seeded cryptic codes among websites, in a music video, and on a quietly released vinyl record. The Internet, puzzled and intrigued, scoured the Web for the codes, eventually finding they could be used to unlock pre-ordering the album.

Jack White, embracing analog rather than digital, put out "Lazaretto" on a limited "Ultra LP" with tracks hidden under labels, an embedded hologram, and other trickery. "It's the biggest selling vinyl album in, I don't know, decades," enthused Caulfield. "He found a way to make people purchase something, a tangible item. That's hard to do!"

It would be easy to dismiss these rule-breaking releases as mere gimmicks, but each weird new idea has its roots not just in selling more records, but in improving and personalizing the fan's experience. It's part of a large-scale movement away from music as product, toward music as community.

"How do you reach your fans? That's where tech has been a huge benefit," said Bakula. "If you're at all socially active online, it's impossible not to know what's going on with your favorite artist. You're hearing what they say, you're pre-ordering, you're seeing their shows, you're connecting."

Bandcamp's Jervis agreed: "Our success is because fans feel like they're interacting directly with the bands."

The ability to connect directly, and the freedom to make and promote records with full creative license — these are powerful tools, and what we're seeing is just the first wave. It could be a renaissance for musicians and the industry at large.

"Digital sales are down. Sales as a whole are down. But that doesn't mean music as a whole is in trouble," said Bakula. "They're doing things which five years ago people wouldn't even try, and 10 years ago wouldn't even have been possible — and 10 years from now we'll be having the same conversation."

He concluded: "Things are going to get crazy."