Thousands of volunteers are lining up to help fight cancer, map faraway planets and record the drama of war. They don't need Ph.Ds or specialized equipment to do it. Instead, crowdsourcing is letting ordinary people solve big problems with a few spare minutes and a Web browser.

At the University of Iowa, volunteers for the DIY History project have transcribed nearly 50,000 documents ranging from intimate wartime diary entries to recipes written in the 1600s.

"Twenty years ago, none of this would have been recorded," Gregory Prickman, head of special collections at the University of Iowa Libraries, told NBC News. To actually look at these documents before 2011 — when DIY History launched in anticipation of the sesquicentennial anniversary of the American Civil War — people would have had to visit Iowa City and dig through the archives.

Now, anyone with an Internet connection can access them. Projects from other institutions appeal to bird-watchers, people willing to analyze cancer slides and history buffs who want to transcribe some very, very old documents — as in papyri from Greco-Roman Egypt.

The potential pool of volunteers? It reaches across the globe.

Exploring space from your couch

"Back when I was a kid, I usually read about Galileo and Herschel discovering moons and planets and I never thought I'd be doing similar work as those giants," Arvin Tan, 25, of Naga City in the Philippines, told NBC News.

He is part of Planet Hunters, a Yale-led project that has attracted more than 300,000 volunteers to look for alien worlds.

Searching outer space for planets is a lot less glamorous than it sounds. Basically, it involves spotting outliers on a big graph which represent a planet moving in front of a star, dimming the amount of light that reaches NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope.

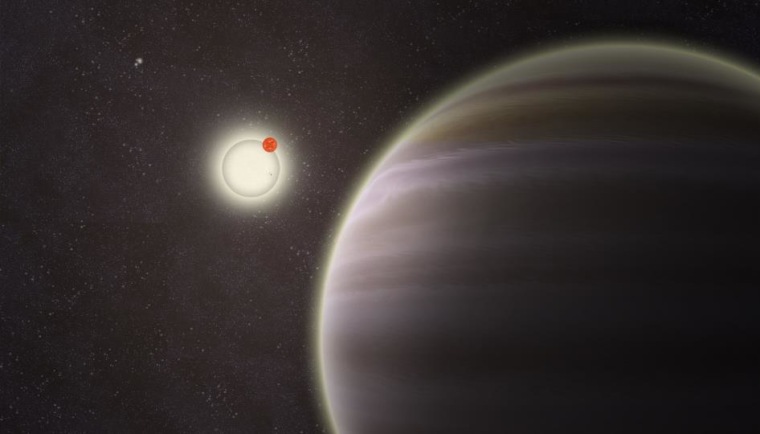

But that doesn't mean it can't be exciting. In 2012, scientists confirmed the existence of what the project's volunteers had initially discovered — a gas giant called PH1 that orbits two stars, like Tatooine from "Star Wars." Even more bizarre: those two stars were orbited by two other stars, making a four-star planetary system, the first of its kind ever discovered.

Those kind of discoveries are what make Tan, an undergraduate studying electrical engineering, commit three to four hours a day studying graphs of starlight.

"I do so not only because it's fun and addictive but also because it increases the chances of finding a new planet," he said. "It actually feels good to spend free time doing real work, knowing I'm not wasting time."

Beyond the history books

History projects can be a little more personal, like rifling through someone's possessions. Volunteers dutifully transcribe government documents, private journals and letters filled with drama.

World War I army nurse Louise Marie Liers (pictured at the top) is just one of the women profiled in the DIY History project. Her volunteer-transcribed letters, originally sent from Nevers, France, to her family in Iowa, mostly implore her parents not to worry about her. Occasionally, however, the horrors of war make their way through.

"When I see their horrible wounds or worse still their mustard gas burns or the gassed patients who will never again be able to do a whole day's work — I lose every spark of sympathy for the beasts who devised such tortures and called it warfare," she wrote.

The Smithsonian is another institution trying to make history more accessible. Siobhan Leachman, 34, would need to take a 22-hour flight to get from her home in Wellington, New Zealand, to Washington, D.C., home of the Smithsonian. She visited the museum once, when she was living a little closer in London as a 20-something.

Now she gets to work with the Smithsonian for two to three hours every day, helping categorize its massive bumblebee collection and transcribe the diaries of naturalists Vernon and Florence Bailey, who trekked across the Western United States in the late 19th century and early 20th century observing plants and animals.

"I love Vernon and Florence Bailey," she told NBC News. "You really get to know people when you're working with their diaries. They were never intended to be transcribed and put out there, so you get to know the real person behind them, and they are lovely, just lovely people."

It's one thing to read an encyclopedia entry about a historical figure like Florence Bailey. It's another to discover intimate moments she recorded while visiting Los Angeles in the fall of 1907, like experiencing a sunset while walking on the beach.

"As the sun came thru low under the clouds, it lit up the Santa Monica cliffs," she wrote. "Another night a few people watch the sun go down in the Pacific — a red ball — then a red disc as it went out in the clouds."

Leachman, like Tan, described the process as "addictive." It's something that Prickman, at Iowa, has also heard that from volunteers, including one who said he felt "a loss" when he realized that the author of a Civil War diary he had transcribed from front to back had died shortly after the last entry.

"It's really the narratives that hook people," he said.

Their enthusiasm makes life easier for the university's academics, who can search for dates and specific terms instead of poring through endless documents, Prickman said. It has also drummed up publicity for the school's library collections and has even prompted a few people to send in their own historical documents.

Eventually, he said, this kind of transcription could be common practice for research institutions across the country — which the University of Iowa is trying to hurry along by making the code for its DIY History project available to everyone.

"If you are doing this, you are a scientist, because you are contributing," said Leachman, who has convinced her mother to start transcribing as well. "People don't realize how much stuff is in museums around the world, just sitting there and waiting for someone."