Just mental humming of your favorite tune, a mental reconstruction of your favorite yoga move, or focusing on your favorite color could soon unlock your computer.

Say you were wearing that computer — as you might if you owned Google Glass. A "passthought" reader that decoded your EEGs would be way more convenient than typing in a password on a real or virtual keyboard.

"You can see all these pictures of Sergey Brin wearing this Google Glass," John Chuang, a professor at theSchool of Information at UC Berkeley, told NBC News. "What if he puts down his Google Glass, and someone else picks it up? Does that mean that someone else can access his photos, start messaging his friends?"

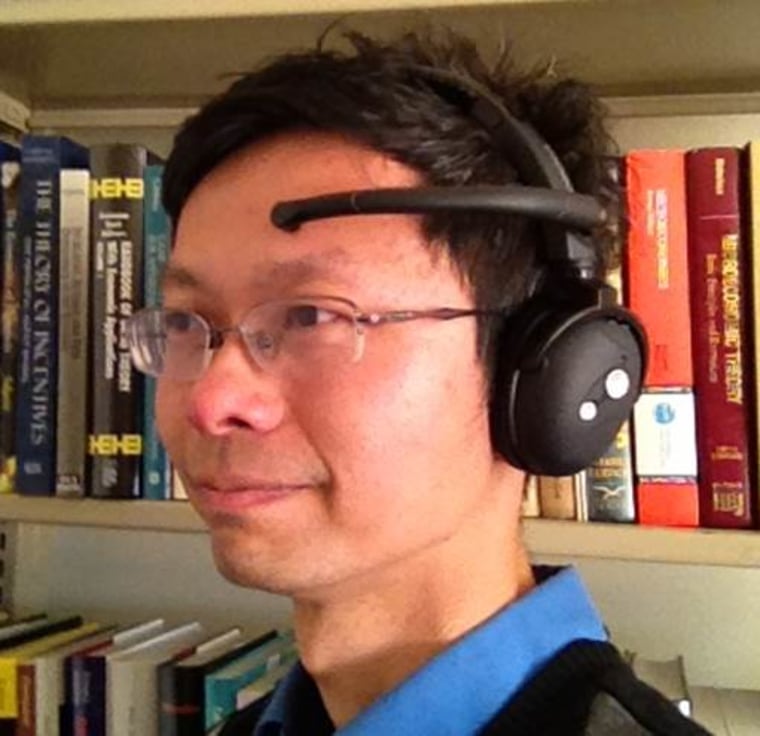

Chuang and a group of researchers at the School of Information ran a series of experiments in which they tested how user-friendly an EEG authenticator would be. The headset they used, a MindSet made by NeuroSky, looks like a pair of Bluetooth headphones and costs about $200, and has one electrode that picks up EEG signals from your forehead and wirelessly transmits that data to a computer.

The volunteers trialled seven different "passthoughts." Among those, they thought about humming their favorite tunes, mentally re-enacted a favorite athletic stance, even just closed their eyes and breathed in deeply. Altogether, and with several repetitions, the scientists collected 1,050 brainwave samples, and were able to reliably match them to the person who made them with an accuracy of 99 percent.

Researchers have been investigating multi-channel EEGs as authenticators since 2005, but this is the first study to show that an affordable, non-medical EEG reader can pick up a reliable signal. More than that, the test subjects seemed to enjoy using a brainwave reader potentially in place of a password.

So what if someone wanted to break into your device by reproducing your passthought? Or, as Chuang described it: "If I knew your song and how you sang you song, how easy or difficult would it be to log in as you?" Chuang said their recent study hasn't tested passthought impersonators, but that's next on the list.

If it turns out others can reproduce your EEG by thinking the same thought, then, like your passwords, you'd have to keep them secret, and keep them safe. "No [form of] security is secure unless people want to use it," Chuang said.

Nidhi Subbaraman writes about technology and science. Follow her on Twitter and Google+.