Corporate America is increasingly wading into social and political issues, taking positions on thorny subjects like voting rights in ways that would have been unheard of a generation ago.

Despite calls on social media for boycotts, analysts and corporate branding experts say there is little chance that the companies whose CEOs are speaking out against repressive voting laws will lose sales. The issue took on new urgency this week when hundreds of corporate and celebrity signatories put their names to a statement titled, “We Stand for Democracy” that ran in the New York Times and the Washington Post on Wednesday.

“This is an enormous cross section of businesses… and they're stepping up during a window of jeopardy we’re facing as a country,” said Mark Cohen, director of retail studies and adjunct professor at Columbia Business School.

“They’re feeling like they have to take a stand,” said Matt Kleinschmit, CEO of Reach3 Insights, a market research firm for brands. “If you’re a CEO today, you have a balancing act, making sure you're living up to the expectations of your future consumers, without being over the line in areas where your older customers don’t really expect you, as a private company, to be involved in.”

Walker Smith, knowledge lead in the global consulting division of Kantar, says the current moment might be new, but marks the next stage in a long-running evolution of how Americans interact with and respond to brands. In the first half of the 20th century, Smith said, brand messaging focused heavily on the product. After World War II, that started to shift to an emphasis on the buyer, which had evolved to a celebration of individualism and personalization by the end of the 1990s.

Then, after a generation of looking inward, society turned its gaze outward. “The idea of purpose as something that companies should embrace is not a new idea… but purpose has a new edge to it lately,” Smith said.

“There’s a new era of expectations about social values — we call this the era of the public. People expect brands to contribute more to society,” Smith said. As a result, “It’s much more salient to business leaders today than it was before.”

People expect brands to contribute more to society — and, as a result, it is much more salient to business leaders today than it was before.

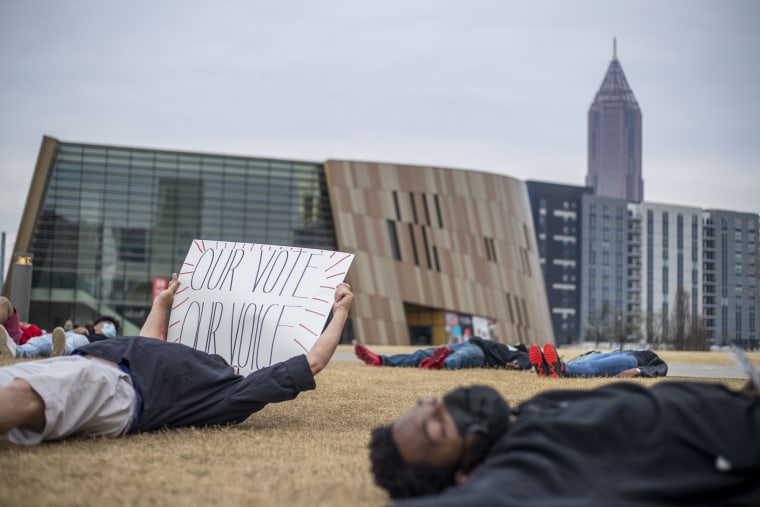

That means that more brands are willing to address thorny political issues, even when that means provoking the ire of a former president. In a rambling statement that included baseless claims of a stolen election and an excoriation of “woke” politics issued in response to Major League Baseball’s decision to move the All-Star game from Atlanta to Denver, former President Donald Trump called for a boycott of the League, along with “Coca-Cola, Delta Airlines, JPMorgan Chase, ViacomCBS, Citigroup, Cisco, UPS, and Merck” — all companies that had made statements supporting voting rights or opposing Georgia’s newly implemented law.

But threats to boycott major companies don’t pack the same punch they once did.

“I think the Nike incident with Colin Kapernick emboldened a lot of companies,” said David Bahnsen, chief investment officer at The Bahnsen Group. When it became clear that the sneaker manufacturer — which tapped the former NFL player to be the face of its “Just Do It” campaign in 2018 — had plugged in to a cause much of its customer base supported, that paved the way for others.

The magnitude of the repudiation of state laws that restrict voting is significant, and there is certainly safety in numbers for the businesses that put their names to Wednesday’s statement. “Americans do not have the attention span for 100 companies,” Bahnsen said.

In addition, boycotts that demand big changes to basic consumer habits — say, shopping at Amazon or searching the web with Google — face long odds, Smith pointed out. “Nothing much happens, largely because it’s kind of hard to change people's buying habits. Convenience is a pretty big driver of brand choice, and habit is the way a lot of brands are purchased,” he said.

Bahnsen noted that some major companies — such as Walmart — are still wary and remaining on the sidelines of the debate. “Nike knew their audience… I’m not sure every company in the Fortune 100 is Nike,” he said.

Corporate chiefs have their personal convictions, of course, but branding experts say it would be naive to believe that there aren’t other factors contributing to this capitalistic calculus. They are canny enough to read the tea leaves and decide that ruffling the feathers of some of their older, more conservative customers will be less disruptive to their bottom line over the long term than alienating the next burgeoning wave of consumers.

“If you're a CEO today, you're walking a tightrope, in many respects. You have increasingly vocal expectations from younger consumers that are rapidly gaining economic power. The Generation Z generation, so to speak, is the largest generation since the Baby Boomers, and they're really starting to enter the market from a consumption perspective,” Kleinschmit said. “If you’re a CEO of a major corporation, you're trying to think about the expectations of that generation and balance that with the expectations of your older customers [who] have lower expectations about the role of the corporate community to bring change.”

A sense of civic duty might also be a motivation. Cohen suggested that CEOs are stepping up because of a lack of leadership from elected officials.

“They’re filling a vacuum. They’re taking the palace of reasonable leaders on the political side,” he said, characterizing corporate resistance to laws that would restrict voting as an explicit repudiation of Trump.

“Most CEOs are intelligent enough, regardless of their predisposition politically, to know damn well this election wasn’t stolen,” Cohen said.