For all the hand-wringing and nervous forecasts, this week's Federal Reserve decision to raise interest rates may be a sign of better things to come.

History rarely repeats itself exactly. But a CNBC analysis of six rate-hike cycles over the last three decades shows that rising rates were often accompanied by falling unemployment, rising stock prices and solid economic growth.

That's not what many Fed watchers have been forecasting. Conventional wisdom holds that central bankers raise interest rates to put a damper on the economy and head off the risk of inflation. The move is like "taking away the punch bowl just when the party's getting started," a quip coined by William McChesney Martin, Fed chairman from 1951 to 1970.

That was certainly the case in the early 1980s, when the Paul Volcker Fed attacked a protracted period of double-digit inflation with back-to-back interest rate spikes that sent the economy into a "double-dip" recession. The cure worked, and interest rates had been on a downward path since.

Examining the results of decades-old monetary policies, though, may have limited value in comparisons with current economic conditions and investment risks.

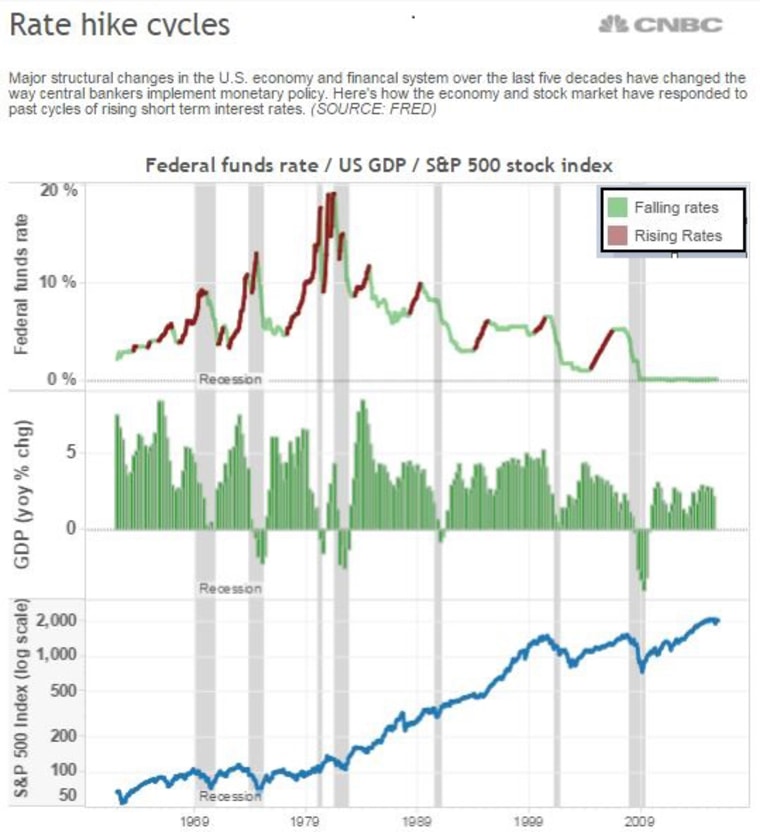

For one thing, major structural changes in the U.S. economy and financial system over the last five decades have changed the way central bankers implement monetary policy. Under the 1960s' Martin Fed, for example, the financial system was still heavily regulated, the economy was in the early stages of a shift from manufacturing to services, and globalization of the credit markets had not yet complicated the U.S. central bank’s job of managing the domestic supply of money and cost of credit.

The latest rate-hike cycle also follows a period unlike any in the Fed's 100-year history, when a global financial collapse forced U.S. central bankers to deploy extreme, untested measures — including a move to slash interest rates to zero and hold them there for seven years to revive a badly broken economy and severely damaged credit market.

Relax, Fed Watchers: Everything’s Going to be OK

Now, after a recovery in both the U.S. job market and financial system — and months of warnings that higher rates were coming — Fed officials this week boosted short-term rates by a quarter-percent and said they expect that "economic conditions will evolve in a manner that will warrant only gradual increases" in this rate in the future.

If past rate hikes are any guide, the odds are the job market will continue to improve and the financial markets will take the hike in stride.

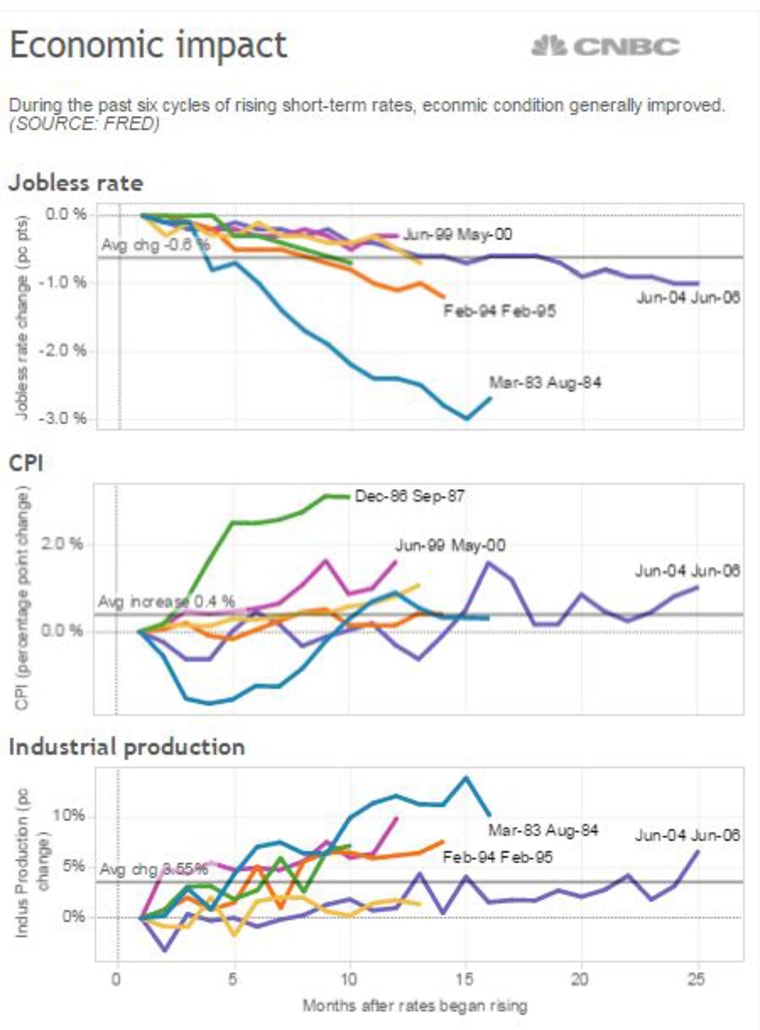

In the months following the last six moves to raise rates, the jobless rate continued to fall — with the biggest job improvements coming in the recovery from the 1981 recession. On average, the jobless rate fell by another six-tenths percent during the last six rate-hike cycles.

Inflation also ticked higher — up four-tenths percent on average — and industrial production bumped up 3.5 percent.

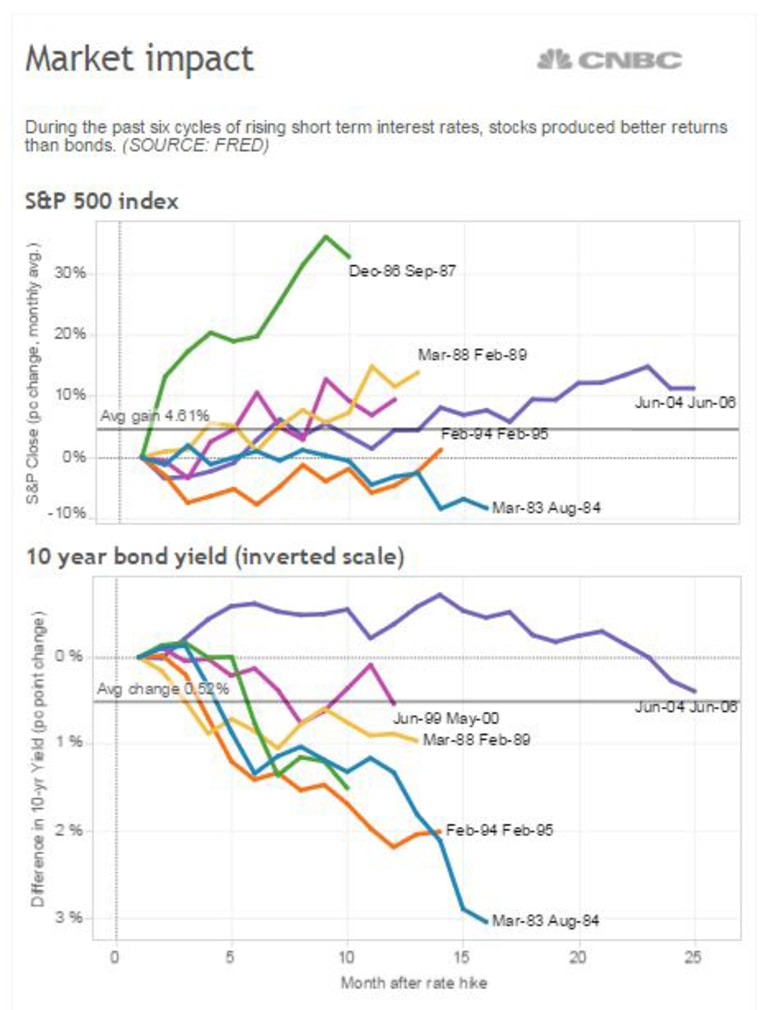

Past rising rate cycles have also helped boost stock prices — up 4.6 percent, on average, based on the S&P 500 index.

Not surprisingly, the results for bond investors weren't as positive. Rising interest rates push bond prices somewhat lower because bonds that were issued with lower yields pay smaller returns than freshly issued bonds paying higher rates. On average, the yield on the 10-year bond rose by 0.5 percent, though the results varied widely during the six rate-hike cycles.

That's just one indication of the perils of comparing past rate cycles to the current one. A lot depends, for example, on how well businesses and investors were prepared for the move to higher rates. The 12-month run of rate increases in 1994, for example, produced the biggest losses for bond investors and left stock prices virtually flat.

That's hardly the case this time around — after months of public statements from the Fed warning of their latest move, no one could argue that the latest rate increase was a surprise.

But while this week's move came with assurances that future increases will be "gradual," it remains to be seen just how quickly — and how far — interest rates rise from here.

"In the end, the pace will be determined by the data and financial markets developments," Jim O'Sullivan, a Fed watcher at High Frequency Economics, said in a note to clients. "We remain skeptical that the pace will be as gradual as is being suggested."

A lot will depend on whether inflation continues to track within the central bank's "target" range, or whether a tightening job market begins to put upward pressure on wages and overall inflation.

History offers little guidance on that score.