It took less than an hour for JPMorgan Chase's CEO Jamie Dimon to dispatch a relatively tame group of shareholders at the bank’s annual meeting in Tampa on Tuesday.

That was the easy part.

Now, the bank’s combative CEO faces two government inquiries and a substantial legal liability from angry investors who have lost more than $20 billion after a series of risky bets inflicted at least $2 billion in losses on the nation’s largest – and once most-admired - bank.

On Tuesday, the New York office of the FBI opened an investigation into JPMorgan’s ill-fated trading scheme, a source familiar with the probe told Reuters. The source, who requested anonymity because the investigation is ongoing, said the probe was in a "preliminary" stage.

The investigation follows a separate inquiry by regulators at the Securities and Exchange Commission, first reported in early April, into JPMorgan's accounting practices. When JPMorgan reported its quarterly earnings on April 13, Dimon dismissed those reports as “a tempest in a teapot.”

Investigators will likely be looking into how well Dimon was briefed on the losses, which began mounting weeks before they were disclosed on May 10. Securities laws require public companies to disclose in a timely manner material information that could affect shareholders’ investments.

With some 850 million shares traded between April 13 and May 10, the bank faces “substantial liability" from shareholders who lost money based on Dimon’s initial assurances, according to Dennis Kelleher, a securities lawyer who heads a Better Markets, nonprofit shareholder advocacy group.

“This is supposed to be a well-managed bank with a CEO who sweats the details with a gold-plated risk management team,” he said. “The lawsuits will be a mile high by the time they’re all filed.”

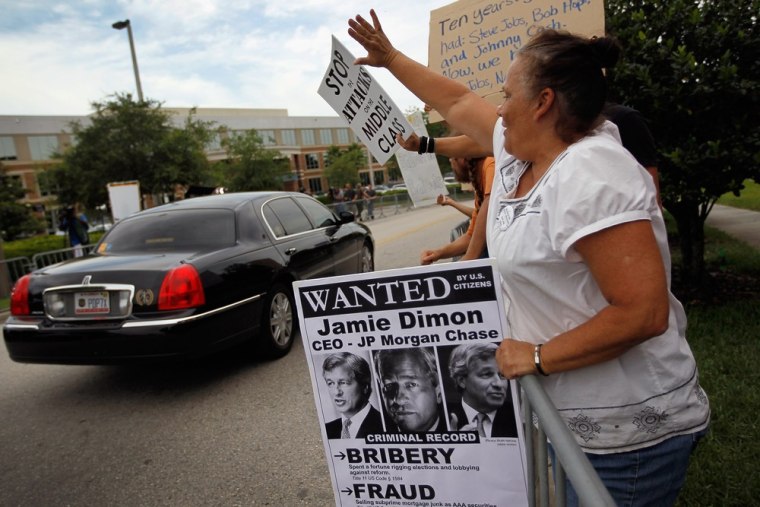

Several hundred of those shareholders gathered Tuesday at a suburban office park in Tampa, Fla., under tight security that had been arranged for a protest that never really materialized. After rushing through his prepared remarks, Dimon listened patiently to series of mild scoldings.

"We heard the same refrain: We have learned from our mistakes. This will never be allowed to happen again," said Rev. Seamus Finn, representing shareholders from Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. "I can't help wondering if you are listening."

Among the shareholder proposals under consideration was a provision to force Dimon to abandon his dual role as chairman and CEO. The move won only 40 percent approval despite the backing of large institutional investors such as the California Public Employees' Retirement System, which argued that a separate board chairman would provide stronger management oversight.

Some shareholders also pressed Dimon on the bank’s failure to provide greater assistance to families facing foreclosure,

“If Chase can afford to gamble with $2 billion without an impact on its bottom line, why can’t it reduce principal for borrowers. We’re talking about real people. They’re not just dollar signs,” Laura Johns, a former housing counselor, told Dimon at the annual meeting.

Dimon and JPMorgan face an even tougher round of questioning from Congress, regulators, federal prosecutors and shareholders.

On Monday, Sen. Tim Johnson, D-S.D., chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, announced hearings in the next few weeks on financial regulation that will include the JPMorgan loss. The hearings are expected to address the question of whether the loss-making trades were “hedges” against wider financial risk – or outright bets with depositors' and shareholders' money.

“Nobody actually knows what was going on because JPM has decided not to disclose what was going on,” said Kelleher. "So you basically have only speculation so far."

Until last week, Dimon had been an outspoken critic of new regulations aimed at restricting so-called proprietary trading that Congress has sought to outlaw since the financial collapse of 2008. He had led his industry’s effort to water down some provisions of the Dodd-Frank regulations enacted in 2009 to curb speculative trading.

The bank’s spectacular trading blunder – the final loss is still been tallied – has bolstered the case for tougher rules to prevent a repeat of the risky strategies that brought down the financial system in 2008. On Tuesday, U.S. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner said JPMorgan's losses strengthened the case for reform.

"The test of reform is not whether you can prevent banks from making mistakes ... the test of reform should be: Do those mistakes put at risk the broader economy, the financial system or the taxpayer?" Geithner said in Washington.

At Tuesday’s shareholders meeting, Dimon struck a more conciliatory tone on the subject of regulating the financial system,

“Our interest is the same as yours: to make it strong and sound,” he told shareholders. “We believe in strong simple good regulations. It’s not simply a question of more or less. We supported an awful lot of what is in Dodd-Frank."

Dimon also faces calls to resign as a member of the board of the New York Federal Reserve, one of JPMorgan’s chief regulators.

Having bankers on the boards of regional Fed banks “is a problem, period,” Sheila Bair, senior adviser at Pew Charitable Trusts and a former chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. told Bloomberg news. “Why the regional banks have members of the industry that they regulate on their boards is beyond me.”