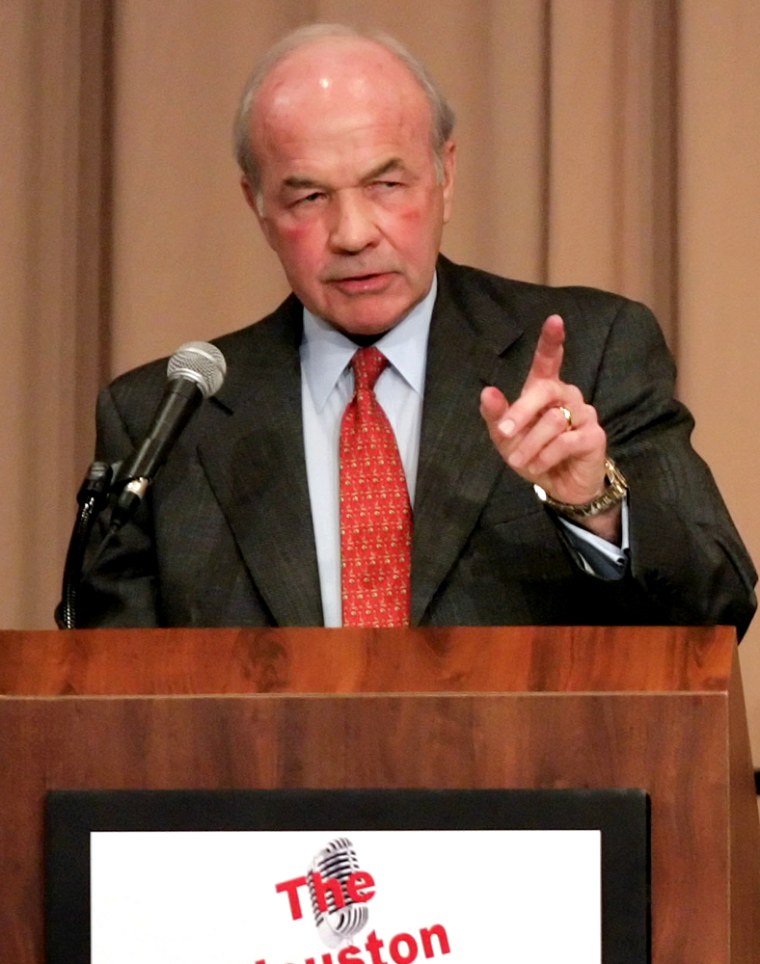

Enron Corp. founder Kenneth Lay launched an impassioned plea Tuesday for former employees of the bankrupt energy company to defy a “wave of terror” by federal prosecutors and help him battle criminal charges.

“It will only take a few brave individuals who are willing to stand up and say it’s time for the truth to come out,” Lay told the Houston Forum a month before he faces trial on fraud and conspiracy counts.

In a speech to about 500 business and academic leaders, Lay repeated his insistence that he committed no crimes related to Enron’s 2001 crash. He accused the government of bullying potential witnesses who could help him and promised to testify in his own defense.

“Truth is a great rock,” he said, quoting Winston Churchill. “Whether it will continue to be submerged by a wave — a wave of terror by the Enron Task Force — will be determined by former Enron employees.”

Lay and his co-defendants — former Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling and former top accountant Richard Causey — have repeatedly alleged that critical witnesses are afraid to talk to them because prosecutors threaten them with possible indictments or harsh sentences for those who have already pleaded guilty. Prosecutors have denied intimidating anyone.

U.S. District Judge Sim Lake, who will preside over the trial slated to begin Jan. 17, said this month that the defense has failed to show any prosecutorial misconduct. The judge also sent letters to potential witnesses saying they can speak to defense teams without fear of government retaliation.

Lay’s speech appeared to be a direct call to those witnesses.

“In this trial, apparently unlike most criminal defense cases, defendants are trying to get the truth in, and the prosecutors — The Enron Task Force — are trying to keep it out,” he said. “They know that is the only way they can win, and I agree.”

Prosecutors declined to respond to Lay’s comments. “The Justice Department will say what it has to in court,” spokesman Bryan Sierra said.

Lay also insisted that Enron was strong until former finance chief Andrew Fastow hatched schemes that fueled financial rot, and that he didn’t know he had entrusted company finances to a crook. Fastow pleaded guilty to two counts of conspiracy in January 2004 and is expected to be the government’s key witness at Lay’s trial.

Tuesday’s speech, which the Forum invited Lay to give, was not the first time Lay has spoken publicly. On the day he was indicted in July 2004, Lay proclaimed his innocence at a lengthy news conference. He then continued to make his case in a high-profile round of media interviews.

But his latest attempt, coming only weeks before the start of the trial, could backfire, experts said.

“This is the kind of speech that can really raise the ire of judges if it can in any way be perceived as an attempt to influence the jury pool,” said Jacob Frenkel, a former federal prosecutor. “Getting up and speaking at this point is treading in dangerous territory.”

Lake has considered issuing a gag order on defendants, their lawyers and prosecutors. The government supports a gag order, but defense lawyers do not. The judge said earlier this month he would monitor public statements and perhaps revisit the issue.

Michael Ramsey, Lay’s lead lawyer, said he hoped his client’s speech would not prompt a gag order.

Lay also blasted the government for prosecuting former Enron auditor Arthur Andersen LLP. The Supreme Court this year overturned Andersen’s 2002 conviction of obstruction for destroying Enron-related documents before the energy company failed in 2001. But that ruling came years after Andersen had effectively gone out of business because of the taint of its indictment and conviction.

Houston Forum chairman Willie Alexander, a longtime friend of Lay’s, told attendees that Lay’s speech may be emotional for some of them given that Enron’s demise left thousands out of work and cost investors billions of dollars.

Skilling and Causey each face more than 30 counts of fraud, conspiracy, insider trading, lying to auditors and others for allegedly knowing about or being in on various schemes to fool investors into believing Enron’s facade of success in the years before the company crashed.

The narrower case against Lay involves seven counts of fraud and conspiracy for allegedly taking over the ruse upon Skilling’s abrupt resignation in August 2001. Lay also faces a separate trial before Lake without a jury on charges of fraud and lying to banks about his intention to use loans to buy Enron stock on margin.

All three have pleaded not guilty.