Every day, Roger Goodell is reminded of the importance of conviction. Hanging on the wall of the National Football League Commissioner's Park Avenue office is a framed letter that his late father, Sen. Charles Goodell (R-N.Y.), sent to President Richard Nixon denouncing the war in Vietnam. Few Republican lawmakers at the time came out against the conflict, and Sen. Goodell's stance would eventually cost him his political career.

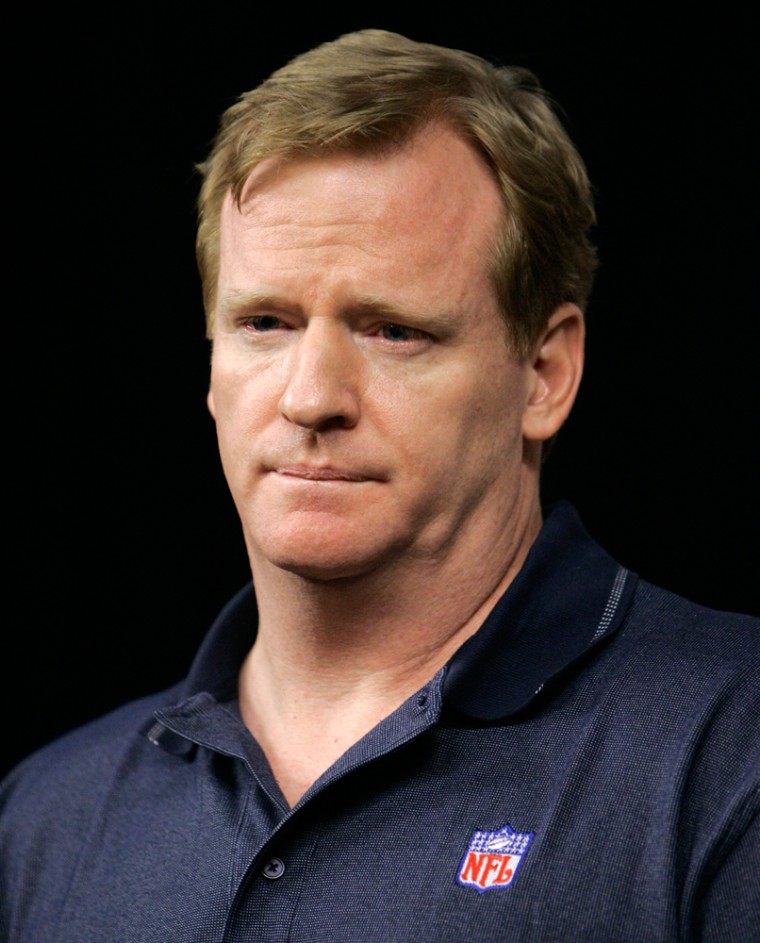

In his second season running the NFL, Goodell is every bit as unbowed as his father when it comes to managing one of the most sprawling, complex businesses in sports. Quick and forceful decisions about quarterback Michael Vick's dog-fighting escapades, Patriots Coach Bill Belichick's spying on an opposing team, and new policies to protect players who suffer concussions are helping to define Goodell as the kind of executive who goes with his gut. That management style sets him apart from his predecessors: the cerebral, lawyerly Paul Tagliabue and the smooth-talking marketer Pete Rozelle.

But the 48-year-old former high school jock (he lettered in three sports) will need all the conviction he can muster if he is to protect the NFL's stellar brand and push the league, whose yearly revenues top $6 billion, to the next level. "It's an awesome responsibility," says Goodell, "not only to maintain the level of success the NFL has, but to build on that." He adds with a laugh, "I am awake a lot of nights."

Goodell isn't especially communicative, but you can imagine what keeps him up: A larger global presence remains elusive, the game's violence and impact on players' health faces greater scrutiny, and off-the-field shenanigans pose potential risks to the league's integrity.

Goodell inherited a league he helped build from a collection of largely mom-and-pop operations into a sophisticated entertainment business requiring consensus among 32 teams and leaders of the players' union. He has spent his entire career at the NFL, starting out in 1982 as an intern in the league's public relations department. A quick learner, Goodell caught the attention of Commissioner Rozelle and became a key deputy to Tagliabue. He credits both for where he is today. "They taught me the important aspects of the job," he says. "And that was my MBA. That was my opportunity to learn about how you can do this job as well as possible, and do it your own way." Goodell was put in charge of initiatives that drove the NFL's growth over the past decade — billions of dollars in TV rights deals, corporate sponsorships, and new-stadium construction. That's why even though some 185 names were floated initially as possible successors to Tagliabue two years ago, including Condoleezza Rice and Jeb Bush, the job was always considered Goodell's to lose.

Goodell tends to view the NFL as a large corporation with 32 divisions. The fans are his customers. "We operate at a very high level," he says. "I talk to CEOs that run Fortune 500 companies about what they do to be successful. And we apply some of the same principles." Among his confidants are Bob Iger of Walt Disney, Jeff Immelt of General Electric, and Sam Palmisano of IBM.

At the league, Goodell's inner circle of advisers includes a team of executive vice-presidents: Eric Grubman, a former Goldman Sachs banker; Jeff Pash, who once worked at the same law firm as did Tagliabue; Joe Browne, longtime public relations chief who started at the league as a high schooler; and Steve Bornstein, the former head of ESPN who oversees the league's cable channel, NFL Network. Among the issues about which Goodell has sought advice: preparing a disciplinary conduct policy for players; bringing the operation of NFL.com in-house (it had been outsourced to CBS SportsLine.com); and shutting down the money-losing NFL Europa. The league's international strategy will now center on hosting up to two regular games abroad — a move Goodell hopes will win over new fans as the sports of baseball and basketball are now doing.

Goodell also has been talking a lot about bringing more innovation to pro football. For example, he is considering putting Motorola transmitters in the helmets of offensive linemen so they can hear the quarterback. That would help keep players from jumping offside, meaning fewer penalties and a faster game. And while he sees TV as the best way to reach fans — after all, the networks, ESPN, and DirecTV pay the NFL $3.7 billion a year for the rights to air games — he is constantly assessing the changing media landscape. "There's a whole new generation coming up," he says. "We have to be responsive to that."

What worries Goodell most, though, is complacency, allowing the years of success as a brand and a business to convince the NFL it is unassailable entertainment. Making the tough calls on Vick and Belichick was the easy stuff. Staying No. 1 is something else altogether.