In the months after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, government officials and industry leaders talked excitedly about how they expected technology to plug many of the gaps in airport security.

They envisioned machines that would quickly detect explosives hidden in luggage, spot plastic explosives or other weapons through people's clothing, identify a flicker in the eye of a suspicious character.

But six years later, little has changed at airport checkpoints. Screeners still use X-ray machines to scan carry-on bags, and passengers still pass through magnetometers that cannot detect plastic or liquid explosives. The Transportation Security Administration has yet to deploy a machine that can efficiently detect liquid bombs, forcing millions of air passengers to check bags or pare down their toiletries to three-ounce containers in carry-on baggies.

Delays could have consequences

The sluggish pace of technological innovation and deployment has left holes in checkpoint security that could easily be exploited by terrorists, according to government officials and outside experts. Congressional investigators reported last year that they were able to smuggle bomb components through checkpoints despite new security measures. Other investigative reports questioned the government's efforts to get emerging technology into the field.

"The snail's pace of deploying new technology is unacceptable," said Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-Miss.), chairman of the House Homeland Security Committee. "We remain vulnerable because we have not kept up with technological innovation."

The TSA in coming months is expected to begin the government's first substantial investment in new checkpoint security technology since the 1970s, according to officials at the TSA, which plans to spend about $250 million on new devices, up from about $89 million last fiscal year. The machines include upgraded X-ray equipment that will provide multiple views of bags and hand-held scanners that can detect liquid explosives in bottles after they are identified by screeners.

Still, TSA officials say it will take years for much of the new technology -- some of which isn't really so new -- to reach checkpoints across the nation. And they are not sure whether the upgrades will allow them to lift nettlesome restrictions on gels and liquids in carry-on luggage.

Lawmakers, government officials and independent analysts point to myriad reasons for the slow deployment of technology at checkpoints.

Lack of private investment

Top TSA officials blame limited private investment in security development. The security industry blames a lack of federal funding and criticizes the difficulty of navigating a bureaucratic approval process that one executive described as "a maze." They also say frequent turnover in the top ranks of the TSA has sent mixed messages. Congressional investigators have raised concerns about the TSA's strategic vision. And top government security officials remain skittish about quickly deploying technology before they believe it has been fully vetted.

The problems actually started before the 2001 terrorist attacks, when there were few security or technology companies investing much money in such equipment, government officials said.

Even after the attacks, there was no surge in investment, and the TSA was given two mandates by Congress that had little to do with upgrading technology at checkpoints: hire tens of thousands of screeners to take over security from private firms, and buy hundreds of machines to inspect checked bags for explosives.

Major gaps in screening

Security experts had long worried about how easy it would be for a terrorist to smuggle a bomb onto a plane in checked luggage. The government spent more than $5 billion over the years to buy, maintain and install explosive-detection systems, which basically scan bags using medical imaging technology, according to government records.

Meanwhile, the government spent only a fraction of that amount -- about $600 million from 2001 to 2007 -- on technology to be used at checkpoints, including upgrades of X-ray machines and devices that can analyze a swab taken of passengers' clothing for traces of explosives.

Even when companies did approach the TSA with new ideas, government officials said they were less than impressed with the results.

"Company after company, trying to be helpful and make some money, was pushing their technology. . . . After testing it, we found it didn't do near what they promised," recalled John Magaw, the TSA's first administrator.

Overseas attacks raise red flags

By 2004, TSA officials believed they were being confronted by another serious security threat: Terrorists suspected of hiding plastic explosives under their clothes slipped through security and blew up two Russian jetliners. Magnetometers -- the ubiquitous metal detectors that have long been a staple of airport security -- would never have spotted such explosives strapped to terrorists' bodies, so the TSA increased the number of pat-downs of passengers, a move that angered some travelers.

TSA officials also rushed to purchase scores of explosive trace portal machines, known as "puffers" because they blast air on passengers and then analyze particles that float off their clothes or skin for hints of a bomb. The agency bought 200 of the machines from General Electric and Smiths Detection, a unit of Smiths Group of Britain, and planned to install them at scores of airports.

By mid-2006, however, TSA officials had found that that the machines could not be deployed in main security lines because they took too long to screen passengers, and they often broke or were unreliable because they could not withstand the dust, grime and jet-fuel fumes in airports. Annual maintenance costs soared to as much as $48,000 for each device. The TSA has plopped 109 of the devices in a Texas warehouse, where they are to remain until officials and vendors come up with ways to make them operate more efficiently.

Agency taken to task

The puffer problems, in part, led the Government Accountability Office to conclude in a report last year that the TSA has not been particularly effective in getting new technology to checkpoints. The report, issued last February, "found that limited progress has been made in developing and deploying technologies due to planning and funding challenges."

The GAO partly blamed the delay on the government's troubles in "coordinating research and development efforts." It also noted that "TSA does not yet have a strategic plan in place to assist in guiding its efforts to acquire and deploy screening technologies." The GAO reiterated much of that criticism in follow-up documents.

TSA Administrator Kip Hawley countered that the TSA and the Department of Homeland Security have come up with a strategic plan and work well with their counterparts to develop new technology.

Hawley said the lack of new technology at checkpoints has more to do with private industry than anything else. Companies do not invest a lot of cash in devices that only have a limited pool of demand: several hundred U.S. airports.

"The real story here is that the capital markets do not value the security industry as a place to put their capital," Hawley said.

Revolving door at TSA

Hawley, who took the top TSA job in mid-2005, is the longest serving of four administrators since the agency was formed by Congress in late 2001. The agency has gone through three chief technology officers. Some vendors said that high turnover rate has not helped matters.

They also complained about the difficulty in getting scientists, bureaucrats and top officials to sign off on devices.

Mark Laustra, vice president of homeland security for Smiths Detection, said it "can be a bit of a maze to get from concept through development."

"The TSA has to review all potential technologies and test them to see if they are practical for the checkpoint," Laustra said, adding that he thinks the government sufficiently funds development of emerging technology. "This process takes time, and then the lab and others like homeland security and TSA have to agree to pilot a program."

Privacy debate adds to delays

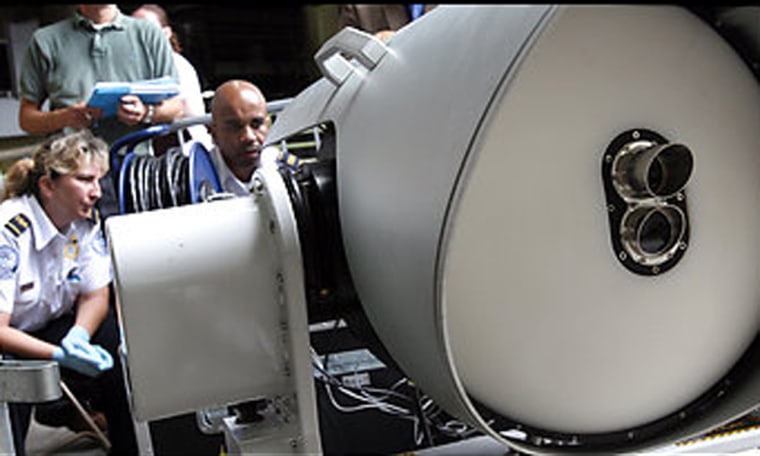

Various factors have complicated the deployment of other high-tech gadgets. After the 2001 attacks, so-called backscatter X-ray devices were hailed by security experts as a critical tool in finding explosives. The machines work by scanning a passenger with a low-intensity X-ray beam that provides screeners with a photograph of what lies underneath the traveler's clothing.

Although the machines have been in commercial service for at least a decade, their deployment has been delayed several times because officials were worried about violating passengers' privacy.

The TSA has taken steps to shield passengers' privacy by erecting closet-sized, windowless rooms where screeners study backscatter images but cannot see the passenger. That installation process alone costs more than $20,000, TSA officials said.

The TSA also has mandated that vendors blur the images of the passengers, a move that the manufacturers and security experts have said might result in a screener missing an illicit item.

The devices, which cost more than $100,000 a piece, have other limitations. For example, they take about 45 seconds to complete a scan, a time lag that would probably lead to massive checkpoint congestion if they were installed in main security lines.

New generation of screeners

Hawley said he sees promise in backscatter devices but expressed more enthusiasm for another emerging technology: millimeter wave machines, which can see through clothes by analyzing the reflection of radio frequency energy bounced off passengers.

One such device is being tested in Phoenix, and the TSA has announced plans to buy eight more for $1.7 million to test at other airports. It works much faster than backscatter, which may open the door to using it as a primary screening device like the magnetometer, Hawley said. But it also requires the TSA to construct separate rooms and to train screeners to analyze its images, which are not as clear as those produced by backscatter.

"There is no perfect technology," said Hawley, who is also taking a less ambitious approach to upgrading checkpoint X-ray machines.

Rather than buy expensive machines that are similar to those scanning checked luggage, Hawley has opted to buy 250 less-sophisticated X-ray machines that take at least two views of a carry-on bag instead of the single view generated by current machines. Hawley said that will give screeners a better shot at finding banned items.

Most will be deployed by the end of the year, Hawley said, adding that their software can be easily upgraded to adapt to emerging threats.