These aren’t great times for CBS. It’s no longer the network ratings champ; its radio business is dragging; and a recessionary economy is bad news for a company dependent on advertising revenue. So it isn’t exactly surprising that the company felt it needed to do something dramatic. What’s surprising is that it has chosen to shell out almost two billion dollars to buy CNET Networks, a venerable but not very profitable Internet company.

Both companies’ executives promised that the deal made perfect strategic sense. It turns CBS into a “top-ten presence” on the Net, giving it access to those eighteen-to-thirty-four-year-olds whom advertisers love, and it allows for cross-promotional opportunities across myriad media. CNET CEO Neil Ashe, claimed that it will make the two companies “bigger, bolder, and better than we could be apart.”

That’s what they all say. In fact, corporate marriages only rarely end in bliss — many studies have found that most mergers and acquisitions do little for the acquiring company’s bottom line. A KPMG study of seven hundred mergers found that only seventeen per cent created real value, and that more than half destroyed it. And a McKinsey study of mergers that took place in the 1990s found that less than a quarter generated excess returns on investment. Perhaps CBS’s experience will be different, but shareholders clearly don’t think so. The day the deal was announced, the company’s stock price fell by almost two-and-a-half percent.

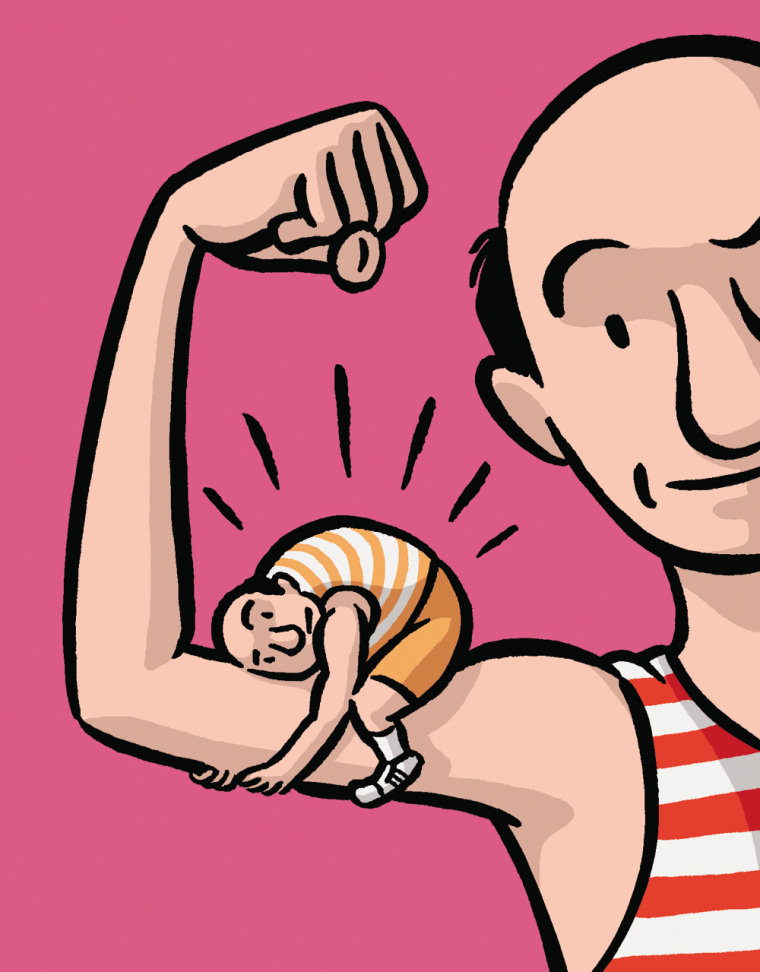

Investors are right to be skeptical. To begin with, the logic of the deal depends on the myth of synergy, an idea that appeals to executives’ sense of themselves as magic-workers. As Warren Buffett once put it, executives see the companies they acquire as handsome princes imprisoned in toads’ bodies, awaiting only the “managerial kiss” to set them free. Unfortunately, most toads turn out to be as warty as they look, and magic kisses are harder to bestow than executives think. Only a few companies today — GE and Cisco come to mind — have been consistently able to take acquired firms and improve their performance and profitability.

(Msnbc.com is a joint venture of Microsoft and NBC Universal, a unit of GE.)

Merger mania also rests on what you might call the fallacy of ownership — the assumption that you have to own a company to make money from its properties. In fact, much of what mergers are supposed to accomplish can be achieved through partnerships and alliances.

Google has made deals to handle searches and advertising for companies like AOL and IAC, giving it access to their customers without the hassle of an acquisition. And IBM has, in recent years, marketed the products of its competitors Sun Microsystems and Novell, enabling it to expand its offerings and its potential customer base. If CBS and CNET had simply agreed to cross-promote each other’s brands and distribute each other’s content, CBS would have had many of the benefits of merging without the costs.

There are, of course, situations in which acquisitions do make sense. According to a recent meta-analysis of a number of merger studies, mergers that rely more on cost-cutting — combining back-office operations, eliminating redundancies, and so on — than on promises of vast growth are more likely to be successful. (The merger of J.P. Morgan and Bank One, for instance, led to more than three billion dollars in annual cost savings.) Acquisitions of smaller, younger private companies are usually wiser than acquisitions of publicly traded firms. They’re more likely to give you access to new technologies or products, and you’re more likely to be able to make the deal at a good price.

In 2000, for instance, Microsoft paid less than $40 million to buy the video-game developer Bungie, the creator of Halo. In the six years that Microsoft owned the company, Bungie’s products generated well over $1 billion in revenue for Microsoft. When you buy a publicly traded company, by contrast, you typically have to pay a steep takeover premium. And that matters, because, arguably, the best hope of making an acquisition work is doing the deal at a bargain price.

Unfortunately, the CBS-CNET merger fits none of the criteria for a good deal. The overlap between the two companies is limited, and so are the opportunities for cost-cutting. And, because CNET is neither small nor privately owned, CBS paid a 45 percent premium on CNET’s stock-market price. That means that, for the deal to work, it will need to improve CNET’s performance not by a little but by a lot.

Rationally speaking, then, it’s unlikely that this deal will end up making CBS money. But the deal was not driven solely by that consideration. CBS is also trying to fight the perception that its business is slowly fading away. This isn’t unusual. CEOs of public companies often feel what you might call the “grow or die” imperative — if the company isn’t growing briskly, they worry, investors will abandon it in search of better opportunities.

This fear often has a basis in reality — Wall Street analysts, for instance, have been pressing CBS to do something to revitalize the company — and CEOs should worry about increasing shareholder value. But while acquisitions, almost by definition, boost a company’s growth rate, they too often make it bigger without making it better.

It’s the rare CEO, of course, who’s comfortable presiding over a shrinking empire, and running a public company creates a bias toward action, if only as a way of convincing investors that you recognize your problems and are dealing with them. But history suggests that, when it comes to mergers, the best response is often to just say no. In effect, deals like the CNET acquisition are a bit like an aging outfielder taking steroids in order to stave off the boobirds. The difference is that steroids usually work.