Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who could face the death penalty for his role in the Sept. 11 attacks, has been peppering his lawyer with questions in advance of his arraignment Thursday before a military tribunal.

It will be the first public appearance for the No. 3 al-Qaida leader since his capture in 2003, and his lawyer, Navy Capt. Prescott Prince, said he doesn't know what Mohammed will say when he addresses the judge Thursday with dozens of journalists in attendance.

"He does not present any anxiety, but it is my impression and belief that this has got to be producing a lot of anxiety for him," Prince said. "It is what could be the beginning of the endgame for him, or the beginning of some level of positive resolution."

Mohammed and four co-defendants are charged with organizing the attacks that crashed four jetliners into New York's World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a rural Pennsylvania field. He could face execution if found guilty of murdering 2,973 people.

But the al-Qaida kingpin hasn't shied away from taking responsibility for such crimes before, allegedly boasting to a military panel last year that he had planned 31 terrorist attacks around the world.

Mr. Prescott meets Mr. Mohammed

Prince, a courtly Virginian called up from the Navy reserves for the case, has spent more than 10 hours in face-to-face meetings with one of the world's most notorious terror suspects. Huddled together in a windowless room at the remote Guantanamo Bay Navy base in southeast Cuba, Prince said Mohammed quickly picked up on the case's legal intricacies.

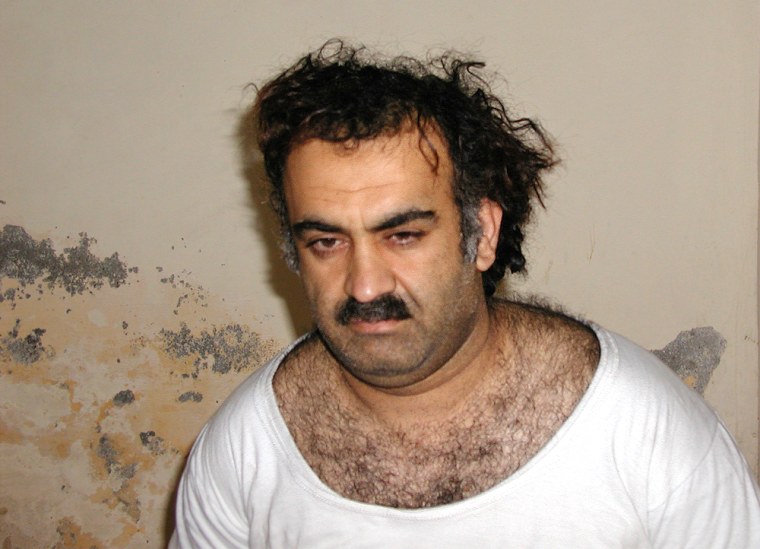

Security rules prevent him from publicly revealing anything his client says or the conditions of his confinement. Prince isn't even allowed to say whether Mohammed still looks anything like the image the U.S. provided to the world after capturing him in a raid in Pakistan in March 2003, of an overweight, disheveled, unshaven man in a T-shirt.

But Prince's impressions provide rare insight into the thinking of a man he says is showing some trust in his American military attorney.

"He is polite. He is appropriate. There are two-way discussions between he and I," Prescott said. "He calls me Mr. Prescott. I call him Mr. Mohammed."

A test case

The trial will not only be a showcase, but a test case, for the military tribunal system the Bush administration has created and defended against repeated legal challenges, including one now pending before the U.S. Supreme Court that could result in the tribunals being declared unconstitutional for a second time.

Prince and other critics say subjecting terrorism suspects to the offshore prosecutions beyond the reach of civilian courts is unfair because they allow hearsay evidence and confessions obtained through coercion.

Prince said he cannot even answer some of Mohammed's questions because the system has yet to be tested by a full trial.

"It is frustrating to me, and frustrating to him, that he's presented with an attorney who in essence says: 'I don't know, the rules are new. They were made up for you,'" said Prince, who believes his client should be tried in U.S. federal court or a traditional military court-martial.

Claims of responsibility

Before and since his capture in March 2003 by Pakistani authorities and CIA officers, Mohammed has claimed credit for proposing to Osama bin Laden the idea of hijacking multiple jets to simultaneously attack U.S. landmarks.

The U.S. alleges that he personally trained some of the 19 hijackers, teaching them English phrases such as "get down," "stay in your seat," and "if anyone moves I'll kill you."

Prince said he is not troubled by defending a client of such notoriety.

"My job is to make sure everyone gets a fair trial," said Prince, a Virginia criminal defense lawyer in his civilian life.

Mohammed was born in Pakistan's Baluchistan province and raised in Kuwait, but he has had much more exposure to American culture than many other detainees at Guantanamo. He graduated from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in 1986, and converses easily in English, stumbling over a word only occasionally, Prince said.

But he also shows flickers of confusion — a possible sign of damage from his imprisonment and harsh interrogations in the secret CIA prisons where he was held until 2006, Prince said.

"The things he says and the questions he asks suggested to me some level of cognitive impairment," Prince said.

Mohammed is one of three Guantanamo prisoners who the CIA says were subjected to particularly harsh interrogation techniques, including waterboarding, which creates the sensation of drowning.