Last year, the New Museum of Contemporary Art on the Lower East Side of Manhattan may have kicked out the frame of the acceptable. We're not talking about a chocolate Jesus or a crucifix in urine, but that my not be too far off.

As part of a $50 million capital campaign, the museum sold a retired venture capitalist, Jerome L. Stern, 83, the right to see his and his wife Ellen’s names writ large — on the museum’s four restrooms. The $100,000-plus loo coup, The New York Times reported, was the first, not the last, naming opportunity the museum would sell to pay for its new home, which opened in December on the Bowery.

Toilets on the Bowery selling for six figures?

News like that makes the burgeoning market for named gifts appear as mind-boggling, overheated and borderline irrational as the Manhattan real estate market, with similar criteria defining value, and similar cost-to-scarcity ratios causing similar price inflation as a seemingly endless flow of “new philanthropists” floods the market.

Just like on Park Avenue, what you pay is determined by what you want to buy. “Getting your name on a building at Columbia University costs more than at Brooklyn College,” says Harvey P. Dale, university professor of philanthropy and the law at New York University. “The prestige of the institution is what matters. It’s going to cost more to become a trustee of NYU than of St. Mary’s College-in-the-Deep-Dark-Woods.”

Price of benefaction climbs

But also just as with Park Avenue apartments, the cost of placing your name in — and on — a choice location keeps going up and up and up. Consider the evidence: in 1967, the Metropolitan Museum of Art raised the price of becoming a benefactor (which gets your name incised into the marble plaques alongside its Great Hall stairway) from $50,000 to $100,000. Today? To be one of those “generations of deeply committed friends of the Museum” you’ll have to cough up at least $2,500,000. One piece of good news, though: you can do that over the course of your lifetime. (But act fast, as the price will inevitably rise again soon.)

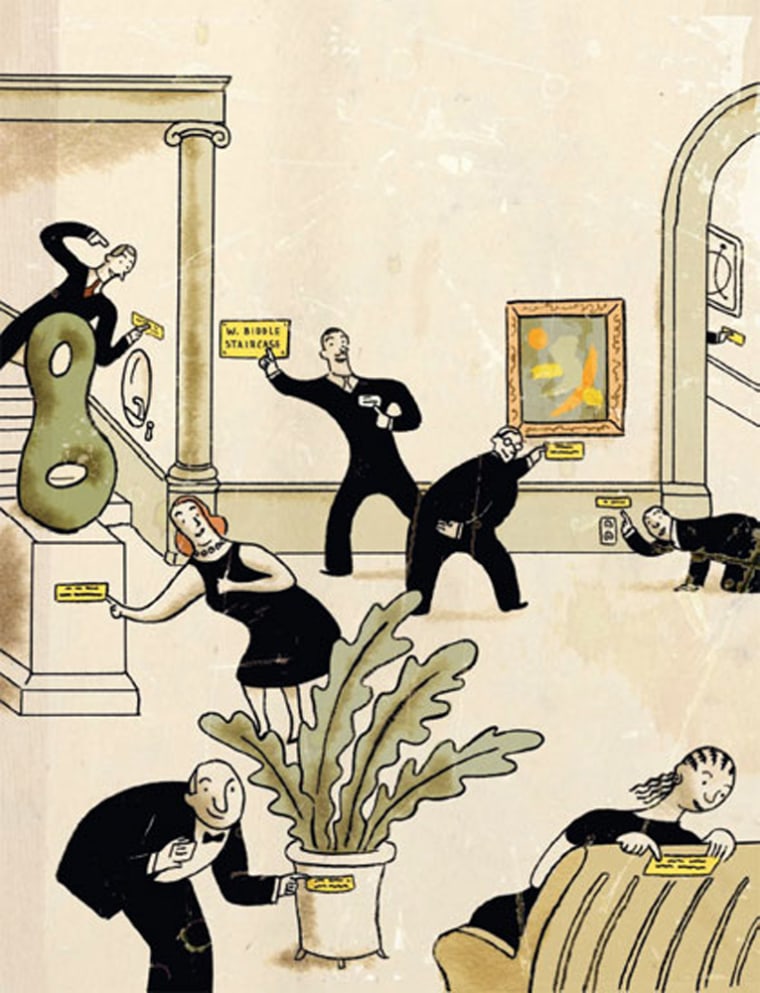

And forget about noblesse oblige. For decades, maybe even centuries, causes and the donors who have financed them have used “named” gifts as the philanthropic simulacrum of a promotional budget. But as philanthropy has become a contest of old wealth versus new, the number of A-List naming opportunities has remained relatively finite, so the price of gilt by association is rising even as development professionals invent ever-more creative ways to raise cash. Small wonder, then, that even toilets have emerged as valuable “real estate” for donors seeking to differentiate themselves. It isn’t hard to imagine that one day soon, some institution or another will boast a Penelope Gotrocks coatcheck carousel, Thurston Howell III motion detectors and Jedediah Clampett rheostats.

Driving the new trend? “All the (newly) available discretionary money,” says fundraising guru Toni Goodale, CEO of Goodale Associates in New York City. “And once the nonprofits saw how successful this was, everything, including bathroom stalls, was being named.” Of course, some things never change: at bottom, naming rights have always been just bragging rights with a nicer name. “If you go to some prep schools in the Northeast, you will see plaques from 100 years ago,” says Goodale.

Institutions broadcast big-name donations to lure others. Even great philanthropists like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie understood that they could do well for themselves by doing good for others — and setting an example in the process. They, of course, were self-assured. Less secure or sincere donors give more for visibility and social validation, positioning themselves as members of an exclusive club—which is not to say that they own up to, or even understand, their motivations.

‘Sometimes ... I want to be high-profile’

“Sometimes, for inexplicable reasons, I want to be high-profile,” the software mogul Peter Norton told The New York Times after giving $1 million for the Signature Theater Company’s Peter Norton Space on 42nd Street and another $5 million for an eponymous theater at Symphony Space on 95th Street. But usually, the reasons are quite explicable.

Some donors are promoting their clan names (the Perelman Quad at University of Pennsylvania, the Ronald O. Perelman Family Stage at Carnegie Hall). Some donors are promoting their personal brands (the Maurice R. Greenberg Wellness Center at the Hebrew Home for the Aged, The Maurice R. and Corinne P. Greenberg Building at the Asia Society, the Maurice R. and Corinne P. Greenberg Division of Cardiology at the Weill Cornell Medical College — itself named for Sanford Weill and Ezra Cornell) which they clearly hope will outlive them. And then there are literal brands (Ronald McDonald House, the SQL Financial Family Lounge at Children’s Health care of Atlanta) seeking to prove they are good corporate citizens.

It’s not just ego, says Doug Bauer, senior vice president of Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors. “It’s values and ego, absolutely.” And sometimes, Bauer adds, it’s also “buying your way into heaven.” According to many across Manhattan's storied benefit scene, Maurice R. “Hank” Greenberg’s benefactions have balanced out some of the less savory attention he garnered while running the AIG insurance group.

Was his philanthropy consciously pre-emptive? We’ll likely never know. These are subjects donors and development people are loathe to discuss. They prefer the public to believe that all is placid and well-meaning in Name World. “The donor (to the Metropolitan Museum of Art) becomes part of a philanthropic tradition that dates back nearly 140 years,” says Harold Holzer, its senior vice president of external affairs. “The museum receives the support it needs to guarantee the preservation and vital presentation of its collections.”

Wanted: Vivid presentation of good taste

But of course, it’s rarely that simple. The “donor” is also paying for a vivid presentation of his/her name and good taste. Among the publicly wealthy, your name on a building is a fourth good reason — after birth, marriage and death — for its appearance in the newspapers. The cause du jour gets not only the cake it needs, but also a cherry on top: a potent reminder to the ambitious of its cultural and social centrality.

How ambitious does one have to be? The Metropolitan Museum provides a glossy price list of “opportunities for donor recognition,” ranging from $10,000 for a plaque beneath a piece of art and $50,000 for a gallery bench to that $2.5 million you’ll have to cough up to place your name on the roll call of New York society on the Great Hall stairway. Only nowadays, those plaques are getting crowded and are full of corporations, too, so it’s unlikely you’ll be incised in stone close enough to J.P.Morgan to feel warmed by the glow of his name. Better, perhaps, to give the “minimum gift of $3 million” required for a named curatorial position “similar to the naming of a university chair.” No word on the cost of a toilet stall.

There are relatively inexpensive naming opportunities. In Sheboygan, Wis., Kohler Credit Unions put its name on two high school gift shops for $60,000. The principal’s office in the Newburyport, Mass., high school was up for grabs for $10,000.

Business school naming rights, perhaps oddly, generally sell for less than those for medical schools. Patrick and Lore Harp Mc-Govern gave $350 million for the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, David Geffen gave $200 million for his School of Medicine at UCLA. But the Tepper School of Business at Carnegie Mellon cost only $55 million and the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas, Austin, was named for a mere $50 million after “Red” McCombs, a San Antonio car salesman. Still, in 2006, Stanford University sold the name of its Graduate School of Management to Nike founder Phil Knight for an impressive $105 million.

Kenneth Lay YMCA?

Just do it? Well, no, one may want to pause first. Name games can lead to trouble as well as tribute. For every Rockefeller University, there is a Kenneth Lay YMCA like the one in Katy, Tex., which had to rename itself following the late Enron chairman’s conviction for corporate fraud and conspiracy.

And sometimes, there’s a real train wreck, like when New York’s Metropolitan Opera put investor Alberto W. Vilar’s name on its Grand Tier in recognition of a $20 million pledge but removed it when he failed to cough up the cash and was soon indicted for an unrelated fraud (the trial is set for September 2008). Luckily, donors are like subway trains, there’s always another: Sid and Mercedes Bass replaced Vilar’s pledge as an outright gift (with a $5 million kicker in cash besides). That’s what one might call hitting a high note.

But careful how you treat those donors. The family of Andre Meyer, former head of Lazard Frères, nearly came to blows with the Metropolitan Museum some years back when it rebuilt its European Painting Galleries, and the Andre Meyer Galleries disappeared. Family members thought his name would grace those galleries in perpetuity. The museum’s bosses were reportedly furious that Meyer had promised it his art collection but reneged on what would no doubt be called an “unenforceable oral promise.” When his family refused the museum’s request for another donation for its new galleries, the museum removed Meyer’s name. Descendents now joke about “the Andre Meyer wall.” To be sure, you don’t always get what you paid for. (The Museum declined to comment.)

‘The definition of perpetuity has changed’

The family of Avery Fisher had more luck when it heard that his name might be removed from his hall at Lincoln Center, endowed with $10.5 million in 1973. The family was no longer flush enough to pay for a new building, so no one even bothered to ask them to “top-up” his gift. But — surprise! — they had enough to hire a lawyer and force a compromise: the interior could be renamed but not the building. “Donors have to be very careful,” says Rockefeller’s Bauer. “Institutions have to be very clear. The definition of perpetuity has changed.”

Indeed, what was once a gentleman’s agreement is now a legal negotiation. Law firms have emerged that specialize in naming gifts and they can play hardball. One specialist, who asked not to be named, tries to win clients the right to withdraw endowments and disassociate their names if, for example, a religious institution becomes a secular one. He also touts the value of “deeds of gift” with provisos, barring charities from changing the terms without a court order. “Otherwise they can run amok and embarrass your name,” he says.

Ultimately, though, only money talks—and so loudly sometimes that some donors even have begun to demand the right to get their money back should the buildings that bear their names be torn down. “Whose need is greater?” asks lawyer William Zabel, who represented the Fisher family. “In most cases, the power of wealth is greater.”

So, when the Wal-Mart billions came a-calling, one school couldn’t say no. Elizabeth Paige Laurie’s parents, Bill and Nancy—whose father, Bud, cofounded Wal-Mart with his brother, Sam Walton — paid $25 million to have the University of Missouri’s new arena named after their then 22-year-old daughter, even though she attended the University of Southern California. But before a single game was played in the Paige Sports Arena, ABC’s 20/20 revealed that Paige Laurie had paid her freshman roommate about $20,000 to write her papers, e-mail her professors, and so forth, throughout her college career. Missouri would not say if it had returned any of their money, but the school renamed its arena Mizzou, its nickname, and Paige returned her USC diploma.

New trend: Egoless naming

Naming isn’t always a crass exercise, though. Increasingly, philanthropists are naming things for others — a new trend in giving. One recent example of egoless naming comes from Alexandra Lebenthal, president and CEO of Alexandra & James, Co., a New York wealth management firm. Lebenthal took part in a quiet little campaign to name a children’s reading room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new educational center for Felicia “Flis” Blum, who’s spent 30 years there training the docents who give tours of the museum. Blum’s husband and Liz Peek, a writer and wife of the head of CIT, the financial services firm, raised the money secretly from friends like Lebenthal and sprang their surprise on Blum at a recent dinner in her honor in the American wing.

“It was really the opposite of ego,” says Lebenthal, who hopes the next big thing in philanthropy will be what she calls “Shhh-don’t-tell fundraising.” She is doing her part to make that happen. “I’m in the midst of raising money for my own secret naming effort,” she reveals. “I can’t talk about it more than that, but someone else in the city is going to have a big surprise soon, so people who know me should have their guard up — and their checkbooks open.”

And even though it goes against the current, they’ll have to keep their mouths shut, too.