Victor de la Paz was riding back from school on a January evening with a friend, just three blocks from home, when uniformed men emerged from the darkness and motioned for them to stop.

Moments later, a soldier opened fire with an assault rifle. De la Paz, 16, slumped to the ground in his bloodied school uniform, already fatally wounded as the soldiers wrestled his body from the car.

The army said the boys ignored commands to pull over, but Victor's father said shots were fired without enough warning.

Mexico's National Human Rights Commission has documented 634 such cases of alleged abuse by the military since President Felipe Calderon sent more than 20,000 soldiers across the nation to take back territory controlled by drug traffickers.

But $400 million in drug-war aid just approved by the U.S. Congress doesn't require the U.S. to independently verify that the military has cleaned up its fight, as many American lawmakers and Mexican human rights groups had insisted.

Instead, the money comes with few strings and no yearly evaluations — exactly what Calderon wanted.

"The U.S. government has finally recognized that this is a shared problem, a bilateral one," Interior Secretary Juan Camilo Mourino said Friday.

Mexico's ruling party had complained that tying the money to a U.S. evaluation of Mexico's human rights record would violate national sovereignty. And many citizens defend the military, arguing that soldiers can't be hamstrung by fears of human rights investigations as they risk their lives confronting drug traffickers.

"The enemy is not very respectful of human rights," said Mexico City banker Roberto Gutierrez.

The drug cartels that supply cocaine to U.S. consumers have killed more than 4,000 people since Calderon took office in December 2006, including more than 450 police, soldiers, prosecutors or investigators.

Crime has dropped in some areas since soldiers arrived, and Calderon's bare-knuckles fight has helped make him the second-most popular president in the Americas behind Colombia's Alvaro Uribe, according to a Mitofsky poll this month.

Reports of human rights abuses by military

But human rights groups say the military operates with impunity, torturing and killing innocents and pillaging homes. And while the army says it punishes soldiers when internal investigations prove abuse, it rarely shares details with the public.

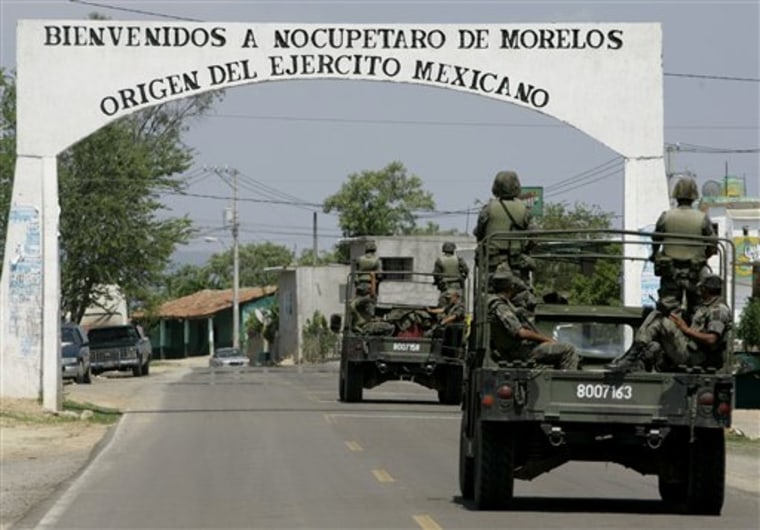

Michoacan, a largely rural state whose Pacific coast and rugged mountains easily hide marijuana plantations and cocaine shipments, has seen the most abuse allegations. It is Calderon's home state, and the first place he sent soldiers after taking office.

In the scrubby hills of Michoacan's Tierra Caliente region, Juaquina Romero's voice falters as she recalls the night soldiers broke through her door without a court order and took her husband away to be interrogated and beaten.

The Army suspended several soldiers who took part in the raid, but it changed forever how Romero feels about her home town of Nocupetaro, where soldiers went on a house-to-house rampage in May 2007 after their security patrol was ambushed.

"They took him, I didn't even know where," said Romero, a 36-year-old mother of five. "Nothing is normal anymore."

Her husband was released without charges and underwent surgery for liver damage from the beatings. He gave testimony to human rights groups, then fled north and is working in construction in California.

Army's training criticized

Rights groups have seized upon Nocupetaro and similar raids as evidence the army is not properly equipped and trained to fight a battle in which traffickers often meld into the local population and many residents are reluctant witnesses.

"We've seen actions that are taken somewhat blindly," said Victor Serrato Lozano, of the Michoacan rights commission. "They arrive in a community and carry out what they call 'a clean sweep.' They raid all the homes."

Under the approved language of the U.S. aid bill, the State Department has to report that Mexico is investigating any abuses, following its own anti-torture laws, and making information on cases public and transparent.

Experts on Mexico's military say the army is rarely transparent now.

"It's certainly true they don't inform people. It generates the impression that the abuses are not punished," said Jorge Chabat, of the Mexican research group CIDE.

Mexico's Defense Department did not respond to written and verbal requests from The Associated Press for information about abuse cases or an interview with its internal human rights office director.

Growing resentment of military

In towns across Mexico where soldiers are directly confronting traffickers, residents who once supported the military presence are now becoming vocal opponents. Nowhere is this more true than in the dry valley that is home to Huetamo.

Hipolito de la Paz, a former soldier himself, has never been able to meet with the army about his son Victor's death in January.

State and local officials promised afterward to help the 67-year-old jewelry repairman move out of his one-room apartment with half a roof, but never came up with the money. Victor's younger brother Cesar, now an only child, avoids soldiers in the street.

"I feel rage when I see the them," the 15-year-old said.

'Missing half your heart'

Outside the state capital, Morelia, Maria Teresa Cruz still cries through the night over the killing of her 16-year-old son, Carlos Garcia. He was shot to death at the gates of a military training camp.

Garcia and a friend came to the camp each day to collect scraps of food for a neighbor's pigs, an odd job that earned him $20 a week. But when the teenagers pulled up on May 12, a soldier apparently fearing an ambush opened fire on their pickup, killing Garcia and wounding another youth whose car had broken down across the two-lane highway.

Garcia's body was still warm when his mother pushed through the crowd to embrace him.

"The pain is like missing half your heart," said Cruz, whose son had hoped to enlist himself one day.

She said soldiers warned her family to keep her quiet, but that only enraged her more.

"I really wanted to take one of their guns and kill them one by one, because each time we passed by there my son always greeted everyone," Cruz said. "I don't know what he saw in that place. He saw some kind of beautiful castle."

She later sought answers from an army colonel, who offered sympathy and some compensation instead. She refused the money as an insult, and took up a collection to pay for the funeral.