Evidence is mounting that Saturn's moon Enceladus has water somewhere beneath its frozen surface, analysis of recent flybys by the Cassini spacecraft shows.

"It's virtually impossible that we don't have liquid water some place in the body," Carolyn Porco, the head of Cassini's imaging team at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo., said during a press conference at the American Geophysical Union conference in San Francisco this week.

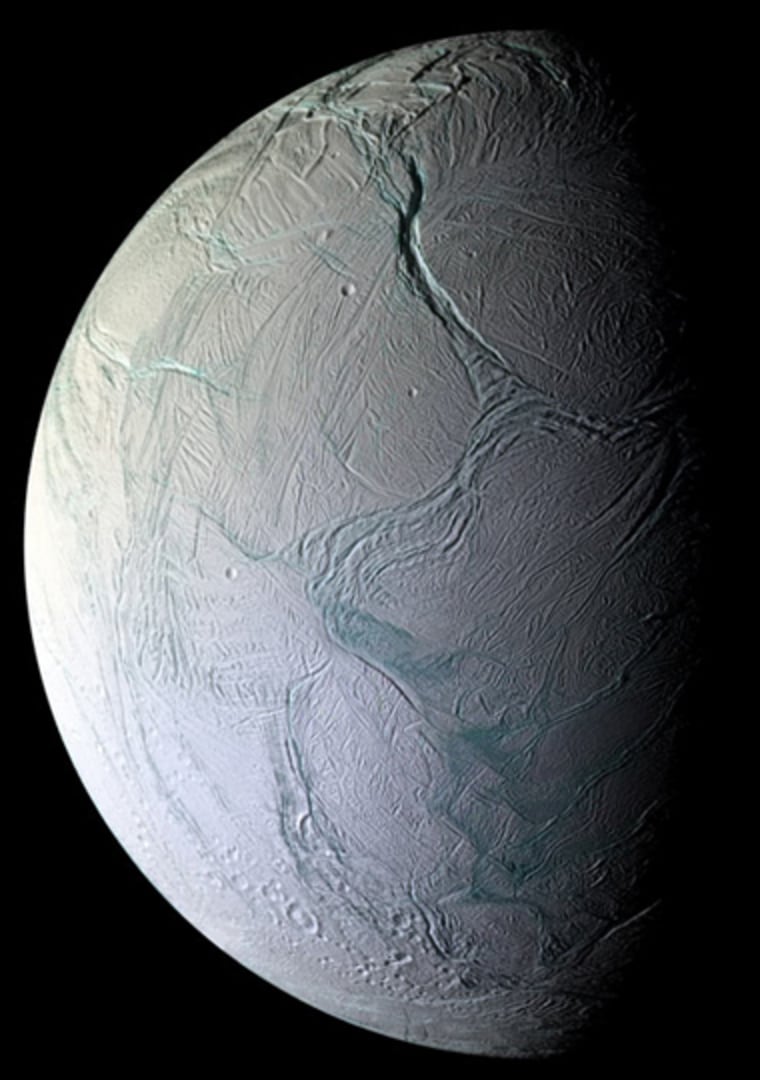

One of the biggest surprises of Cassini's ongoing mission at Saturn was the discovery of geyser-like jets shooting streams of organics-laced ice and water vapor out into space. Cassini flew as close as 15.5 miles above one of Enceladus' fractures, warm spots scientists call "tiger stripes," during its last pass over the moon in October.

The jets of ice particles of water vapor spew from vents inside the fractures.

Scientists have enough information to conclude that the face of Enceladus changes over time, with some vents opening and others closing due to tectonic forces similar to what occurs on the floors of some of Earth's oceans where volcanic material wells up to create new crust.

On Enceladus, however, the spreading is almost entirely in one direction, like a conveyor belt, rather than multi-directional like on Earth.

"We are not certain about the geological mechanisms that control the spreading," said Paul Helfenstein with Cornell University in New York.

"It's very unusual. You wouldn't find something like this on Earth."

The mechanism is similar enough to Earth-like systems, however, to suggest that subsurface heat and convection are involved, he added.

Scientists also have discovered that Enceladus' vents seem to open and close sporadically, possibly because ice occasionally plugs the holes until pressure builds and the geysers erupt anew.

The heat driving the cycle is due to gravitational forces acting on Enceladus from Saturn and neighbor moons, Porco said.

"It can't be anything other than tidal flexing because we have no other possibilities," she said.

The Cassini team also discovered that Enceladus, as well as Saturn's largest moon Titan, are contributing material for the planet's rings and dumping ionized gas from water vapor into Saturn's magnetosphere.

"The plasma is a major driver of magnetospheric activity," said Christopher Russell, a Cassini scientist with the University of California, Los Angeles, who measured bends and other changes in Saturn's magnetic field over time.

Cassini's next pass by Enceladus is scheduled for November 2009.

"We are very excited and feel very fortunate to have stumbled upon such a fascinating place," Porco said.