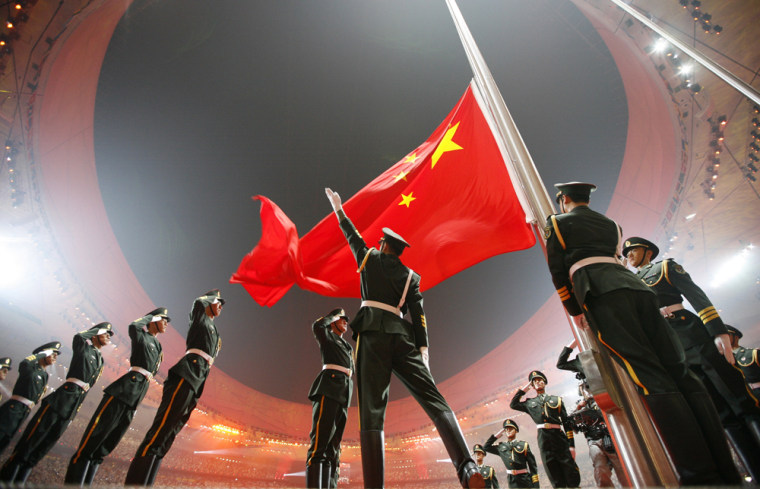

BEIJING – The number eight is considered so auspicious here that the Chinese leadership decided to launch the Summer Olympic Games at 8 p.m. on the eighth day of the eighth month of the year.

The number eight has long suggested luck and good fortune because in Mandarin it sounds like the word for prosperity, as Raymond Lo, a feng shui expert, explained to us back in July. But, depending on the time cycle mapped out on the Chinese calendar of elements, eight could have positive or negative portents. “This year [suggests] the earth is not stable,” said Lo. “And, also, the number eight also represents children.”

Indeed 2008 turned out to be a turbulent year for China — and two of the worst disasters befalling its youth were the Sichuan earthquake and the baby milk scandal.

The quake, which struck early on a May afternoon, destroyed thousands of classrooms and may have killed as many as 19,000 children out of the estimated 90,000 people killed or missing.

And in September, just two weeks after the Olympics ended, the public learned that a leading brand of powdered baby formula contained melamine (a chemical used to artificially boost the milk’s protein content), which was later reported to have killed at least six infants and sickened nearly 300,000 others.

Between the success of the Summer Olympics and everything else, 2008 was, as cultural critic Raymond Zhou observed, “a year of extremes” for China.

The other lows

The year had a rocky start, with the country’s worst winter weather in 50 years striking southern and central eastern provinces, stranding millions of people trying to get back to their home villages for the Lunar New Year holiday.

In March, riots broke out in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, with Tibetans going on the rampage, destroying Chinese shops and attacking ethnic Chinese residents. The unrest stunned people everywhere in China, who later took umbrage at Western media coverage of the events.

In fact, even as Beijing Olympic officials prepared to welcome the world in August, sentiment here turned nationalistic and somewhat nasty. The patriotic fervor was heightened in April, following repeated attempts by human rights activists and protesters to disrupt the Olympic torch relay in Paris, London, and San Francisco.

Much less widely covered was the unrest which flared up in China’s other troublesome western region, Xinjiang, heavily populated by Uighurs, an ethnic Muslim minority group. In the weeks leading up to the Summer Olympics, a series of attacks, mostly on Chinese police, left more than 30 people dead.

At times, however, Chinese nationalism also found a more positive face.

‘A better society’

“The earthquake brought the best out of the Chinese people,” said the cultural critic Zhou, referring to the nationwide outpouring of volunteerism, charity and aid. “People were more spontaneous, especially in the first few weeks. It really showed humanity and humanitarianism in unprecedented and historical proportions.”

That was especially true among China’s youth, once viewed as dissolute and apathetic. “[China] has come out a better society, where younger people had the experience of looking at people less fortunate than themselves and wanted to do something about it,” agreed Jeremy Goldkorn, founder of danwei.org, a Web site about media, advertising and urban life in China.

The media also came out stronger, despite concerns about the government’s attempts to muzzle the press throughout controversial stories, as well as the Olympics.

“The fact that the Olympics was really a PR success for the country has given the government a little bit more confidence for dealing with the foreign media,” observed Goldkorn, citing the decision to loosen the rules governing foreign journalists conducting interviews and traveling around the country.

The same, unfortunately, can’t be said for the Chinese media. “This should be a record year for what [domestic journalists] got in terms of policy guidelines on what to say and what not to say,” laughed Hung Huang, a popular Chinese blogger and publisher.

It may, however, be a wasted effort by the government. “The Internet has become such an all-pervasive force,” said Goldkorn, “and has become so difficult to control.” Indeed, this year China surpassed the U.S. with the world’s largest number of Web users, and many events – including the quake, the melamine scandal, the boycott of French goods over the French government’s views on Tibet – inspired fierce debate among millions in online chat rooms.

China’s first successful spacewalk in September also brought the country glory, even if it occurred 40 years after America’s.

And then there was the success of the Olympics and the Paralympics – although Zhou described the Games as “the end of the beginning.”

“At the end of the first act, you see a big performance number, it crescendos. That’s the Olympics,” he said, adding, “Act Two starts with the economic downturn.”

The economy strikes

In fact, the global recession poses the Chinese leadership’s greatest challenge at a time when the government is trying to celebrate its 30 that have translated into three decades of nonstop, extraordinary growth.

This month, the country recorded its first drop in exports in 10 years.

“This is our first downturn,” said Hung, the blogger and publisher. “So how we handle it is going to be extremely critical for what kind of country, what kind of economic power China is going to be.”

Exactly how Beijing will steer the course in an economic slowdown is the question gripping everyone, not least economists. “At the start of the year, everybody was worried about inflation [and overheating],” said Andy Rothman, China Macro Strategist at CLSA Asia-Pacific Markets. “Now everybody’s worried will growth be fast enough?”

The big question is will it be enough to absorb the increasing number of migrant workers being laid off from closing factories, as well as new college graduates entering the market. Labor officials have warned that 24 million people are expected to enter the job market next year, competing for half as many openings.

“In China, unemployment could deprive a lot of people of their ability of survival,” said Professor Hu Xingdou of the Beijing Institute for Technology. “So it could trigger social instability or even shake the rule of the [Communist] Party.”

The government’s main challenge

Although some may not realize it, but this is a country accustomed to displays of anger or frustration – the Ministry of Public Security reported 87,000 so-called “mass incidents” during 2005 – and the Communist Party is keenly aware of the potential for rising social unrest exacerbated by rising unemployment. “The legitimacy of China's ruling party is not based on election, but on promises of high speed of economic growth,” explained Hu.

Also key, however, is the party’s response. “If they respond in a way that’s perceived as caring and supportive – the party makes sure I have a place to live, I have food on the table, my kids can still go to school, they can get access to medical care — if they can do a reasonable job of those things, then people will say, all right, they’re doing the best they can under the global circumstances,” said Rothman.

Of all the measures the leadership has rolled out to compensate for weakness in its export-reliant economy, its biggest is a massive fiscal stimulus plan worth nearly $600 billion that is designed to help create more jobs.

Various ministries have sought to reinforce the central government’s message that all its efforts, including the spending plan, will pay off by the second quarter of 2009.

But it is a highly contentious point. “We don’t know if [the stimulus plan] is big enough, and we don’t know if it will happen quickly enough,” said Michael Pettis, who teaches finance at Beijing University.

In fact, Pettis is not terribly optimistic about how the global economy will play out. “I expect trade frictions next year are going to increase significantly and if they’re not dealt with very, very carefully, we will see a real contraction in international trade,” he said.

20th anniversary of Tiananmen in 2009

Tensions of another nature also threaten to resurface next year. March is the 20th anniversary of anti-government demonstrations in Tibet; the large-scale protests back then triggered a state of emergency in the region.

However, that situation was quickly eclipsed by the student movement that emerged in Beijing a month later, which eventually led to the June 4 military crackdown in Tiananmen Square.

Lastly, but least controversially, the People’s Republic of China turns 60 in October.

Even with all the uncertainty, many people here still hope for the best, with Lo, the feng shui expert, offering a reassuring forecast: “Next year will be a bit more calm, even with the financial crisis taking place.”

It would seem about time. As Zhou put it, “The kind of things that happened this year was just too much, even for people like me to take in.”