Baby Amir's crib is lined with blankets crocheted by his mother and stuffed animals from his 8-year-old sister. Framed photos of him hang on the walls and sit atop shelves and tables throughout his family's three-bedroom home.

He has yet to see any of it.

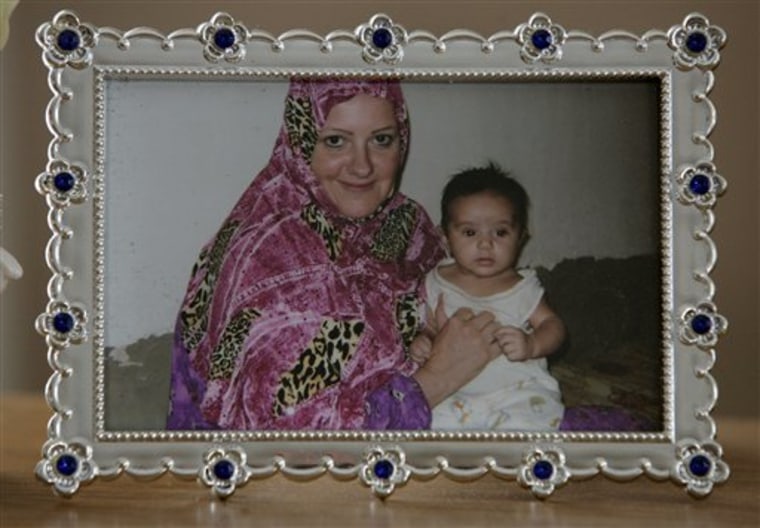

Eight-month-old Amir Alshemmari remains in his aunt's concrete house in the holy city of Najaf in central Iraq, where his relatives' home has electricity two hours a day. His mother, Grace, is more than 6,000 miles away in Fort Wayne, writing letters to everyone from politicians to Dr. Phil looking for help to get her son home.

She's willing to do all but the one thing the U.S. government says she must: take her son to the U.S. embassy in Baghdad to obtain the paperwork proving he is a U.S. citizen so he can get the passport needed to leave the country.

"Just watch the news. You can see Baghdad isn't a safe place," Alshemmari said. "That's where most of the conflict is, and I think that's where most of the anti-American groups have centered their organizations."

Alshemmari, a lifelong Indiana resident, didn't plan to give birth in the war-torn country when she and husband Raad, an Iraqi refugee who came to the United States in 1993, learned she was pregnant with their second child.

Heading to Iraq

The couple met in 1998, had a daughter in 2000 and married in 2007. She had never been out of the country. Her husband convinced her to go to Iraq because his 86-year-old mother was in failing health.

Alshemmari left for the trip almost a year ago, when she was nearly six months pregnant. She planned to return in time for her mother's birthday on April 22 — about a month before her due date.

But the couple and their daughter stayed too long, Iraqi Airways officials said. The airline refused to issue her a ticket to fly home because it does not allow expecting women to fly beyond the pregnancy's 35th week.

Alshemmari, who was 35 weeks pregnant at the time, was devastated, but her husband said they had no choice.

"Let's just have the baby here, and we'll all come home together," he said.

Alshemmari agreed, but told him: "As soon as this baby's born, we're out of here."

She gave birth by cesarean section at a hospital in Najaf, about 100 miles south of Baghdad, on May 25.

Gathering necessary papers

The couple thought they could get the necessary paperwork to bring home the baby by going to Iraqi offices in Diwaniyah, about 30 minutes away. After a half dozen trips and a call to the U.S. embassy, they learned they needed to go to Baghdad.

But her husband's family told her the trip was too dangerous, especially for an American.

"They said, 'We're Iraqi and we don't go there. Don't go there,'" Alshemmari said.

The couple flew to Jordan without Amir in hopes of finding a solution, even though they knew the United States required the baby be present at an embassy to receive the paper proving American citizenship. They were given a seven-day visa, which Alshemmari said wouldn't be enough time to get an appointment at the U.S. embassy there.

"It seems to me she's stuck between a rock and a hard place," State Department spokesman Noel Clay said.

Clay said the Alshemmaris' predicament is rare but that the State Department can't make an exception in their case because its policies for verifying U.S. citizenship guard against baby smuggling.

"We can't change the procedures," he said.

After their unsuccessful trip to Jordan, the Alshemmaris returned to Fort Wayne without Amir in hopes of getting help at home. But so far, little has changed.

"It just doesn't seem to be going anywhere. We're just mired down," Alshemmari said.

'I want him so bad'

The offices of Sens. Richard Lugar and Evan Bayh have been involved in the case since late October, trying to determine whether the family can give power of attorney to Raad Alshemmari's sister, Sadiea, so she can take Amir to the embassy.

Lugar's office also provided access to a computer at his Fort Wayne office that would allow her to see Amir via the Web camera on Sadiea's family computer. Alshemmari, however, chooses to look at pictures and video taken while she was with him.

"I'm torn. I want to see his face. I want to see how he's doing. But then I know it's going to kill me because I don't know how much longer until I get him home," she said. "I want him so bad."