Sixty-five years have gone by since D-Day, but Louis Delevin remembers.

When he was elected mayor of this tiny Normandy village in 1989, Delevin's first gesture was to raise a monument to the U.S. 354th Fighter Group, whose time in Cricqueville local farmers have never forgotten. After the landing at nearby Utah Beach on June 6, 1944, Delevin recalled, young American pilots from the 354th used a grassy meadow here as an advance landing strip for several months, until the German army folded back and the front moved on.

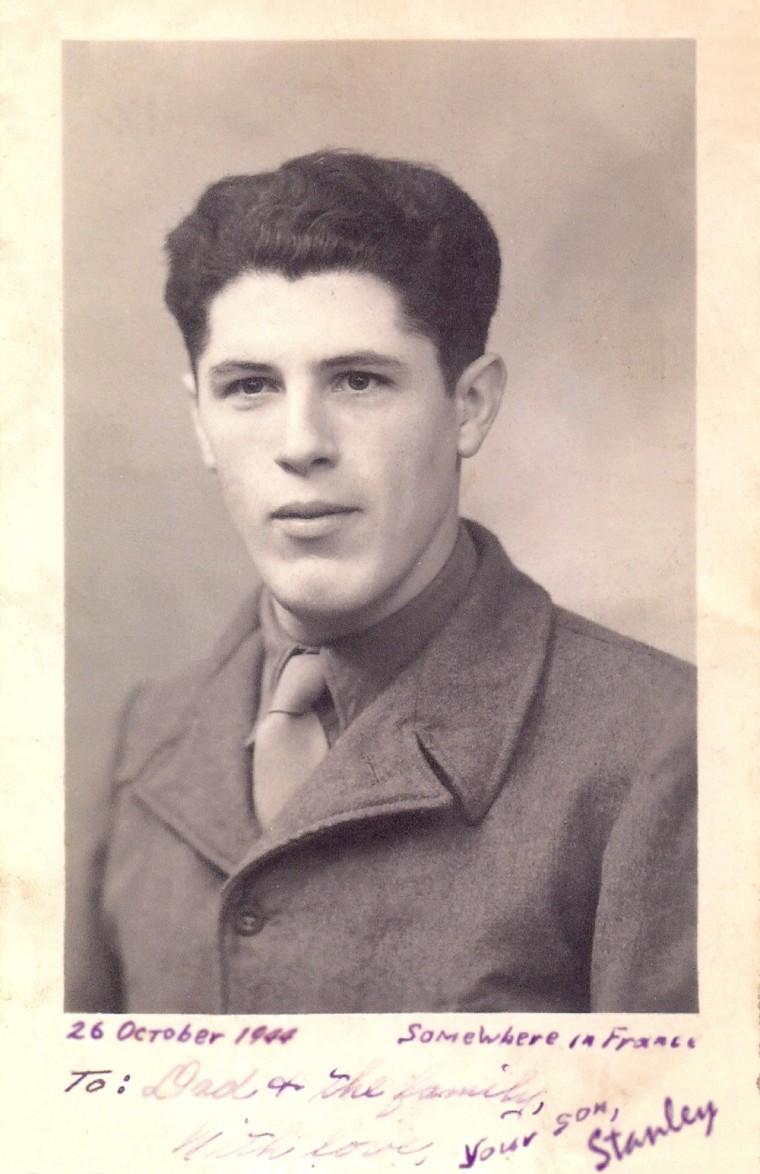

One of the GIs who passed through Cricqueville during that hot summer, according to information discovered recently by the Associated Press, was President Obama's grandfather, Stanley Dunham, who served with an Army aviation maintenance unit that helped keep the strip running.

"If they hadn't come, where would we be today?' said Delevin, 77, who as a farm boy of 12 regaled the pilots with apple cider between raids on the retreating German troops. "You don't have to be a great scholar to understand that the freedom we enjoy today was decided in those days in 1944."

Americans welcome

Up and down the Normandy coast, a rainy stretch of sand and rocks along the English Channel in northwestern France, the memory of what American troops did in that fateful June has remained tenaciously alive, enduring through the political disputes and personal exasperations that often divide leaders in Washington and Paris. Obama, who has scheduled a visit Saturday to the U.S. military cemetery at nearby Colleville-sur-Mer, will find himself in unusually friendly territory here, a place where people like his grandfather are still honored and the image of America as a force for good has remained largely untarnished.

President Nicolas Sarkozy, who will accompany Obama to the cemetery, has gone out of his way since coming to power in 2007 to emphasize the tradition of official friendship between France and the United States. The irritation in Washington created by then-President Jacques Chirac's opposition to the Iraq war has dissipated while, in France, things American are fashionable once again, particularly since Obama's election and President George W. Bush's departure from the White House.

Sarkozy prevailed on Obama to visit the Normandy landing beaches, ensuring that he would be televised by the new U.S. president's side, affirming France's role -- and his own -- as a major player in the world. As it was with his predecessors, grasping at that role has been a major preoccupation for Sarkozy. In addition, the photogenic visit comes one day before European Parliament elections that are seen as a test of his popularity among French voters buffeted by the global economic crisis.

'We haven't forgotten'

But it is in the little towns and villages of Normandy where the ties between France and the United States have remained most deeply rooted. In fact, here they never really faltered, and American presidents have shown up regularly to bask in them: Ronald Reagan was here in 1984, and Bill Clinton had his turn in 1994. Bush came in May 2002.

"When you are 4 or 5 years old, and your parents and your grandparents tell you about this, it sticks with you," said Benoit Noel, 42, who helps administer a museum commemorating what happened on Utah Beach. "Everybody in Normandy remembers the landing. We know what the Americans did for us. We haven't forgotten."

Prayers continue

Here in Cricqueville, for instance, people gather at their little stone church once a year to celebrate Mass in honor of the young U.S. troops who died on nearby beaches or in the surrounding fields. Inside, the U.S. and French flags hang side by side over the tabernacle.

"Christian, do not forget the American soldiers who risked and sacrificed their lives for you along this coast on June 6, 1944," reads a marble plaque fixed to the wall of the nave. "The bell of this church guided them. You owe them to pray faithfully that God welcomes them."

Jean Castel, a former pilot from nearby Grandcamp who has spent years studying the Normandy landings, said the Cricqueville church bell played a genuine role; the little structure and its stone walls were on U.S. military maps as a landmark for forces fighting their way inland after landing at Utah Beach.

Some of those battles have been commemorated at the Cricqueville City Hall, as well, with a series of photos and drawings depicting a celebrated assault by U.S. Army Rangers up sheer cliffs at Pointe du Hoc. A photo of their commander, Col. James Earl Rudder, looks out over the community meeting room under a sign reading, "Honor and Gratitude to the American Rangers."

In the dining room of Grandcamp's Hotel Duguesclin, a wall-size oil painting of the Pointe du Hoc attack has been hung to illustrate the moment for customers feasting on fish brought in from gray channel waters just out the window. In the image, Rangers descending from landing craft rush toward the cliff walls with ladders and grappling hooks while German machine gun rounds send little fountains splashing up from the sea.

Castel said that, in real life, many of the Rangers died before reaching the rocky shore. Allied bombing had created holes in the ocean floor, he said, creating unexpectedly deep pools in which equipment-laden soldiers who jumped from the landing craft in the wrong spot sank and drowned.

'They were the liberators'

Castel, 79, said he has been interested in the Normandy landings, and particularly the air attacks, since at the age of 14 he saw a U.S. B-26 bomber crash near Rouen during a pre-landing raid. After becoming a pilot himself and a civilian employee of the U.S. Air Force in the 1950s, he tracked down the pilot, identified as Dee Mitchell, who had survived the crash and returned home to Texas. Since then, Castel has become an authority, armed with documents showing where and how U.S. and German units fought and died and what happened in each little valley or meadow.

"People here never forget the Americans," Castel said. "For us, they were the liberators."

In addition, the glorification of D-Day is a source of revenue for many Normandy towns. Tour agencies have designed regular circuits for groups of U.S., British and other tourists.

Despite their postwar wealth, Germans have never been very numerous visitors, local officials said, and when they do show up, they often pretend to be Dutch.

In any case, the affections of local Frenchmen clearly have gone to the winners. U.S., Canadian and British flags have become just as common as French flags up and down the coast. Several museums have been erected, and souvenir stores sell GI costumes or replica weapons. Jeeps and U.S. landing craft have been deployed to decorate town squares in communities throughout the region.

But it is not all about selling souvenirs. As they do every year on or near what is called Memorial Day in the United States, about 3,000 people gathered May 24 at the U.S. cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer for a ceremony led by the local prefect, Christian Leyrit. A few of those in attendance were Americans, including visiting veterans of the landing. But most were French, there to remember what led to the dramatic expanse of green lawn overlooking Omaha Beach that is marked by 9,386 white crosses and Stars of David.

History lessons

Such dwelling on the past normally is not part of the world of Mathieu Bonnel, 15, a junior high student with a slicked-up hairdo from a small town near Lille in northern France. But there he was at the cemetery one recent day, along with the rest of his history class, carrying a clipboard with arrows depicting the June 6, 1944, assault and listening to a lecture about who is buried under the long rows of markers and why.

Asked what he thought about seeing the graves of so many soldiers from the other side of the Atlantic, Bonnel looked to his classmates for help in finding a response.

"It's impressive," suggested one.

"Right, it's impressive," Bonnel said.

Delevin, a regular at the Memorial Day observance, had another answer. "Every year I feel something," he said.

More on |