Mali is known — if it is known at all — for being one of the world's poorest and most inhospitable countries. The country, roughly the size of Texas, has a lot of desert and Africa's hottest city, Kayes.

So when I told people I'd gone there for my two-week vacation, I was most often met with the question “Why?” or the belief (maybe hope?) that I'd been sunbathing in Bali.

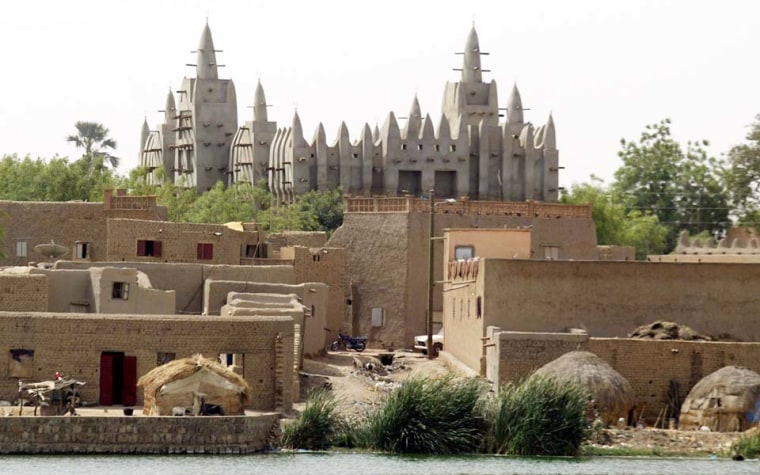

Once you make it to Mali and back, the allure is easier to understand. Mali is a stable country that offers a real sense of African culture as well as a sense of nomadic Arab culture. It’s home to famed Timbuktu, and has the world's largest mud structure, a mosque in the town of Djenne. But the main draws are the Niger, one of the world's great rivers, and its ethnic groups: the Fulani with their tattooed lips and feet; light-skinned Tuareg nomads living in thatch huts low to the ground, and the Dogon, whose detailed knowledge of the stars has led to speculation that they were paid a visit by extraterrestrials.

My trip there was the result of a decision I made to fulfill my lifelong goal of riding a camel in the Sahara Desert. Didn't matter where, for how long, or where to. I just wanted to look out from atop one of these ornery beasts across the dunes of that mythic wasteland.

I arranged my trip through a London-based company called Exodus, which specializes in global adventures for small groups. Exodus, little known in the United States but popular in Britain, offered 10 days of camping and trekking in Mali, visiting tribal villages during a three-day boat ride down the Niger River, and an optional camel ride, in Timbuktu no less. I hadn't even known Timbuktu was in Mali.

The price, excluding airfare: $1,700. I booked it.

Rolling down the Niger

But Mali is not for the traveler expecting turned-down sheets and chocolates on the pillow. About a third is covered by the desert and it gets crushingly hot even in the coldest months between October and February, which is the best time of year to visit.

In the end, I got to Timbuktu and I got my camel ride, but they weren't the highlight. Far more compelling was cruising up the Niger in a 50-foot oversized canoe called a pinasse, gliding past villages that had to be abandoned until the dry season because the river was too swollen.

At times it was so calm and the sky so clear that you couldn't tell where river ended and sky began except for a thin strip of green marshy bank a few hundred yards away. Our only company was the occasional massive pinasse — a cross between a dugout and a canoe, powered by sails of stitched-together grain sacks or children with 15-foot wooden poles — passing the other way.

On our first day on the river, our guide, Hamadou Olouguem, steered us to the first of many villages far enough away from the river. We were welcomed in Dienteja like we were everywhere, with requests for gifts like pens, or plastic bottles, or any article of clothing, but also with genuine amusement and curiosity. You quickly learn that Mali's people, especially in the remote villages that don't get a lot of tourists, are just as interested in studying you as you are in studying them.

Electricity doesn't come out this far. Plumbing was a plastic pipe that sticks out a couple of feet from the second story to an open sewer running through an alley. A few children ran away when they saw us, but later came over to touch my skin and hair; a white person is a rare sight here.

The men who weren't out collecting the harvest or herding sheep rested in the shade while women in long robes of rich blues, reds and yellows pounded millet with a man-sized version of a mortar and pestle.

That night, we camped along the banks of the river, fending off both heat and millions of mosquitos dive-bombing us for dinner. Our own food was prepared by a cook in the tiny kitchen of our boat, usually preceded by warmed hibiscus juice and topped off with an orange or melon slice.

Flexibility, as the trip notes had warned us, was as necessary as bug repellant and sunglasses. Our group — 11 Brits, two Irish brothers and me, the lone American — was a hardy bunch, and we quickly came to accept that anything that could break down eventually would. We also learned that the enormously resourceful Malians can fix whatever implodes with whatever tools are at hand.

For example: In our two weeks, a truck broke down (twice), the engine of our boat died and its steering mechanism later failed, leaving us stranded briefly in the middle of a lake. The Niger was running so high that a key road we had to cross became impassible; and the truck that was supposed to meet us at the end of our boat ride ran a day late.

Don't go it alone

Itineraries in Mali undergo heavy mid-route editing, so a good guide is essential. Some Malians speak French, but many people in the remote areas where you will be going do not. Hamadou spoke six languages — English and French as well as four ethnic tongues — but his true gift was a preternatural calm.

He ran interference by negotiating prices at markets for us and knew where to buy water — not easy, since banks, convenience stores, gas stations and supermarkets barely exist. And he made sure we could always pay despite what became one of our major inconveniences: Mali is so poor that people rarely have any change for the big bills of CFA (African Financial Community) francs you'll change dollars or euros for, and the service mentality hasn't quite arrived. Generally the attitude at restaurants was that the responsibility for finding the proper change lay with us.

Back on land

After three more days of travel up the river, we arrived at last in Timbuktu, on the ninth day of our journey. My chief memory is that it was 120 degrees during the day and painful to venture out between about 12 and 3 p.m.

The city is only a shadow of the center for trade and Islamic learning it was in the 16th century, and has been in decline for 400 years. Walking down its streets is like walking down a beach, and its few sights — three mosques and the homes occupied by the first Western explorers to get there in the middle of the 19th century — can be covered in a morning.

Still, this was Timbuktu. It is, after all, known chiefly for being hard to get to; its air may be choked with sand, but it is also charged with history.

We then headed south to Dogon Country, near the border with Burkina Faso, for two days of trekking around dwellings that the Dogon and their predecessors, the Tellem, had built next to a cliff face, where they were better protected from the animals roaming the forest.

As with the rest of the trip, the unexpected moments were the most striking. We had just spent another 100-plus-degree day hiking around the cliff dwellings. I washed my face in near darkness next to my tent, which was pitched on the roof of a mud hut, when I heard clapping and singing. It was impossible to see where it was coming from because there was little electricity in the town, called Teli. So a few of us went out in the darkness to follow the sound.

We came across about 20 children. The girls stood barefoot in a circle singing a song that required one to enter the middle and repeat a verse. The others would sing a chorus, clap a rhythm, and alternate into the middle. The boys were wrestling, gripping each other in upright stances trying to throw the other to the dirt. If neither was successful after about 10 seconds, another child would hop in to break them apart.

Indifferent to their new audience, the boys wrestled and the girls sang in darkness, the only light the stars and the thick band of the Milky Way draped across the sky.

If you go

GETTING THERE: Royal Air Maroc flies from New York to Bamako with a stop in Casablanca. Air France also has flights from New York to Bamako through Paris. The best way to go is through a tour group, among them Exodus Travel (www.exodus.co.uk), Explore (www.exploreworldwide.com) and STA Travel (www.statravel.com) which is geared more toward students.

DOCUMENTS: A visa is required but easy to get through the Malian Embassy in Washington (www.maliembassy-usa.org or 202-332-2249).

CLIMATE: The best time to travel is between early October and February. Bring light clothing and a raincoat.

SAFETY: The U.S. Embassy advises against going to the far north because of the Group Salafast for Prayer and Combat, best known recently for having kidnapped a group of German tourists in Algeria and bringing them to Mali. But Mali's north is so barren, and so hot, there's not much reason to go there anyway.

HEALTH: Mali requires a yellow fever vaccination and recommends tetanus, hepatitis B, meningitis, typhoid and polio. Call your doctor well in advance of your trip for updated information on what shots you'll need and to set up a schedule for getting them. Anti-malarial pills are essential.