The commission investigating the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks has concluded that the hijackers would probably have postponed their strike if the U.S. government had announced the arrest of suspected terrorist Zacarias Moussaoui in August 2001 or had publicized fears that he intended to hijack jetliners.

A report on the case released this week noted that "publicity about the threat" posed by Moussaoui "might have disrupted the plot." Commission Chairman Thomas H. Kean (R) said the conclusion is based in part on extensive psychological profiles of the Sept. 11 hijackers, who were "very careful and very jumpy."

"Everything had to go right for them," Kean said. "Had they felt that one of them had been discovered, there is evidence it would have been delayed."

Such a delay could have given the FBI, the CIA, and British and French intelligence services more time to discover Moussaoui's ties to al Qaeda and the terrorist cell in Germany that planned the attack. The FBI also might have had more time to track down two hijackers who had entered the country but were not located before the attacks.

These and other findings disclosed by the commission this week make it clear that the scope of missed opportunities in the Moussaoui case was broader than previously believed. A wide array of U.S. counterterrorism officials and foreign intelligence services -- including the director of the CIA -- knew about Moussaoui's arrest but repeatedly missed the clues he offered to the catastrophe that was about to unfold, the reports and testimony show.

The findings have led some commission members and investigators to believe that it is plausible, perhaps even likely, that the terrorists' plan could have been detected if Moussaoui's case had been pursued more vigorously.

"A maximum U.S. effort to investigate Moussaoui could conceivably have unearthed his connections to the Hamburg cell, though this might have required an extensive effort, with help from foreign governments," investigators wrote in a staff report released this week. "The publicity about the threat also might have disrupted the plot. But this would have been a race against time."

Slow to help

Timothy J. Roemer, a commission member and former Democratic congressman from Indiana, said the Moussaoui case "is really a plausible way to deflect parts of 9/11, as plausible as they come."

According to staff reports and testimony this week, CIA Director George J. Tenet and his senior deputies were briefed on the case within days of Moussaoui's arrest, but never told the president, the White House counterterrorism group or even the acting director of the FBI, who learned about the case on the day of the attacks. The CIA brief given to Tenet was titled "Islamic Extremist Learns to Fly."

There were numerous other mistakes, according to the commission and previous accounts. The FBI and immigration agents who arrested Moussaoui in Minnesota as he sought flight training feared he wanted to hijack an airplane, but they were blocked by FBI lawyers from searching his belongings. The FAA was warned Sept. 4 about Moussaoui's clumsy attempts to learn to fly jetliners, but it never warned the airlines or the public. British and French intelligence services were queried, but the British in particular were slow to help.

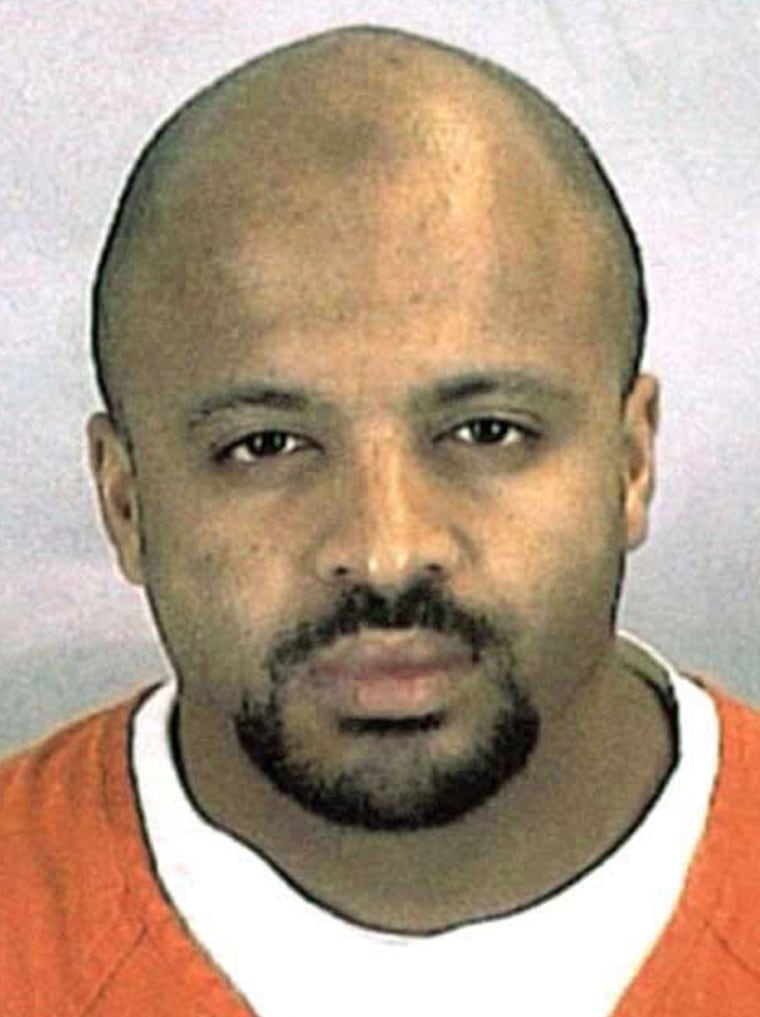

Moussaoui was ultimately charged as a conspirator after the attacks and is jailed in Alexandria awaiting federal trial. He has publicly declared his allegiance to al Qaeda but denied he was part of the plan to strike New York and Washington.

Moussaoui was first detained on immigration charges in Eagan, Minn., on Aug. 17, 2001, by FBI and Immigration and Naturalization Service agents. A flight school in which Moussaoui had enrolled reported that he was hostile and suspicious, and that he wanted to learn to fly a Boeing 747 despite minimal skills or experience.

The staff of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States, as the panel is formally known, recounted familiar parts of this tale in reports released this week. The FBI agent notified headquarters but was rebuffed in attempts to search Moussaoui's laptop computer and other belongings because of legal squabbling over the need for better evidence tying Moussaoui to terrorists, which FBI officials believed was necessary to secure a warrant.

The agent notified the FBI's legal attaches in London and Paris to try to gain more information about Moussaoui, a French citizen and former London resident. And because the Minneapolis FBI office and its lawyer, whistle-blower Colleen Rowley, were frustrated by what they perceived as a lack of interest from headquarters, the agent also contacted "an FBI detailee and a CIA analyst" at the CIA's Counterterrorism Center, according to commission staff and previous accounts.

But what had not been clear before this week was how high, and how quickly, details of the case went from there. Tenet testified Wednesday that he was briefed on the case on Aug. "23rd or 24th." Deputy CIA Director John E. McLaughlin and director of operations James L. Pavitt had learned about it at least a couple days earlier.

'History of jihadists learning to fly'

Despite the apparent urgency with which the arrest was treated and warnings that summer of an impending terrorist attack, Tenet acknowledged that he and his aides did not notify the White House or counterterrorism officials. In part, CIA officials say, this was a matter of protocol: The original information from the Minneapolis FBI agent was passed along outside usual channels.

"We immediately tried to undertake a way to figure out how to help the FBI get data and deal with this particular problem," Tenet testified.

Tenet also maintained that there was no reason, based on the evidence available at the time, to alert President Bush or to share information about Moussaoui during a Sept. 4, 2001, Cabinet-level meeting on terrorism. "All I can tell you is, it wasn't the appropriate place," Tenet said. "I just can't take you any farther than that."

Tenet had told commission investigators that "no connection to al Qaeda was apparent to him" before the attacks.

Roemer said he found it "shocking" that Tenet and his deputies did not share the Moussaoui information more widely, especially in light of the Aug. 6 briefing document that Bush had received about the domestic terror threat titled "Bin Ladin Determined To Strike in US."

"This moved its way up the chain at the CIA very quickly," Roemer said. "Why doesn't it continue to circulate? . . . I would think 'Extremist Learns to Fly' would be treated at least as a discussion item, if not a Molotov cocktail."

Daniel Benjamin, a national security official in the Clinton administration, said, "There is such a rich history of jihadists learning to fly, it is really surprising that more was not made of this."

Two other shortcomings were cited as particularly important by investigators. First, the panel noted, the Moussaoui case "was not handled by the British as a priority." Two days after the attacks, the British discovered information that placed Moussaoui in an al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan -- which would have provided the FBI the evidence necessary to search his belongings. The panel concluded that if the British had treated the case more urgently, they could have learned about Moussaoui's ties to the camp before the attacks.

Second, the commission staff said, U.S. officials failed to check with terrorist operatives in custody, including convicted millennium bomber Ahmed Ressam. After the attacks, Ressam picked Moussaoui out of a group of photos and said he remembered him from the Afghanistan training camp. "Either the British information or the Ressam identification would have broken the logjam," the commission wrote.

One subject of the panel's inquiry not discussed during this week's testimony was a fledgling deportation plan that called for taking Moussaoui on a government jet to Paris, where he would have been turned over to the French intelligence service, which has more leeway to conduct searches. Moussaoui's computer included, among other things, telephone numbers linked to Ramzi Binalshibh, one of the key organizers of the Sept. 11, 2001, plot.

But that plan may not have mattered in the end: Moussaoui would have arrived in Paris on Sept. 17.

Researcher Lucy Shackelford contributed to this report.