Don’t think small things matter? Sometimes a tiny color stripe makes a world of difference.

In the late 1950s, an assistant professor of engineering at the University of Buffalo named Wilson Greatbatch was working with cardiologists on a way to record heart sounds. While tinkering one day, Greatbatch pulled the wrong resistor out of a box.

It was easy enough to do. After all, resistors, which regulate electric current, look a bit like brown ants with wires sticking out either end. Their varying strengths are denoted by a series of color bands less than a millimeter wide.

Greatbatch needed 10,000 ohms — brown-black-orange — but instead grabbed brown-black-green, a resistor 100 times as strong. He checked the circuit; it cycled a brief pulse, followed by a one-second silence. Not great for checking heart sounds, but very much like a heartbeat.

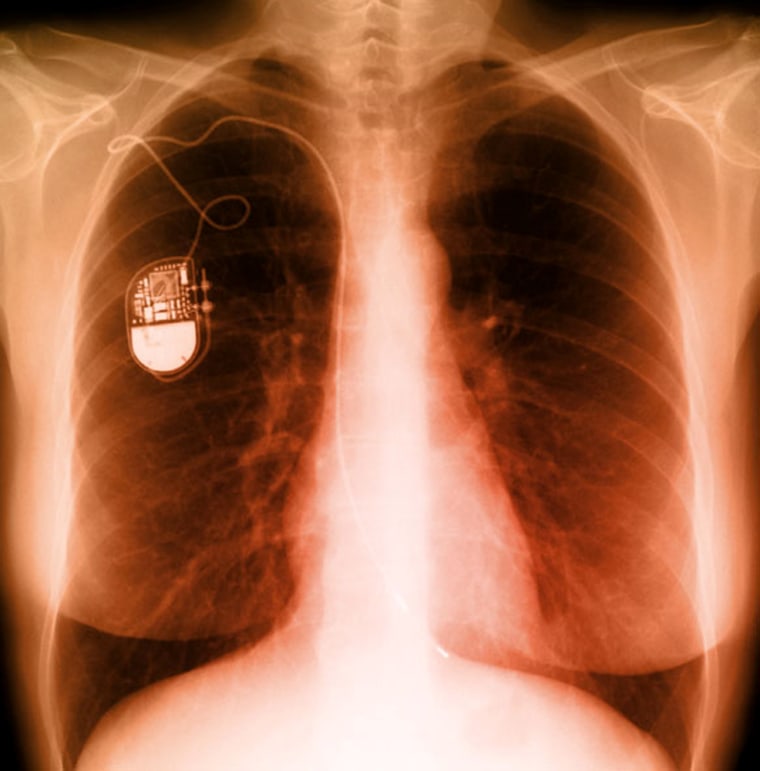

“I said, wait a minute,” Greatbatch says, recalling the moment, “this is a pacemaker.” That simple device has been a lifesaver for everyone from Mother Teresa to Dick Cheney.

The truth about invention, innovation

Serendipity is never that simple. At the time of Greatbatch's chance discovery, crude pacemakers were already available: clunky, TV-sized devices that patients were plugged into for short intervals.

Greatbatch was already interested in the technology and had been working with heart doctors. He and others had envisioned a device that could regulate the rhythm of malfunctioning hearts, yet be small enough to remain inside a patient’s chest.

He just happened to find it while looking for something else. “Someone once said that luck favors the prepared mind,” Greatbatch notes.

Credit for that sentiment goes to another legendary inventor — Louis Pasteur — and it accurately defines the reality of innovation.

The rare accidental invention

Sure, there have been truly accidental inventions. In 1879, Constantine Fahlberg spilled a substance on his hand, found it sweet and soon patented saccharin (to the dismay of his lab partner Ira Remsen, whose name was left off the patent). In 1946, Percy LeBaron Spencer was working with radar waves when he realized the radiation could melt the candy bar in his pocket. Ding! The microwave was born.

But much as we love the myths of these magic moments, learning and preparedness lie behind them. Lucky inventors usually know when they've stumbled upon something momentous, even if the discovery is unintentional.

“When Lewis and Clark discovered Yellowstone and so forth, well, they spent a year in preparation for the trip,” says inventor Art Fry. “The more you learn, the more you are able to see.

“When you see a different pattern of doing something, it’s that ‘Eureka!’ moment.”

An epiphany at church

Fry should know. As a 3M engineer in the mid-1970s, he came upon a mild adhesive created in 1968 by fellow employee Spencer Silver. Fascinating, sure, but it wasn't until Fry was singing in his church choir, wishing for a bookmark that wouldn’t fall out or damage his hymnal, that inspiration struck. That’s right: Post-Its.

“You can’t predict it,” Fry says. “But you can do the work that will lead you to those things."

Sometimes, though, industry isn’t as quick to share in the vision. Fry spent years shopping Post-Its throughout 3M, hoping to convince the brass that companies would gobble them up. Only after a 1978 trial run in Boise, Idaho, was the company sold.

And even genius can use improvement. Greatbatch points out that an implantable pacemaker was just one in a series of necessary inventions. Though a big hit after the first one was implanted in 1960, the pacemaker required rapid innovation: a completely sealed unit, models that only functioned when heartbeats became irregular and, crucially, a lithium battery that could last for years. “Our real business has been implantable power,” he says.

The business case often takes years to make. By the early 1960s, a researcher named Douglas Engelbart had conceived of ways to harness computers so people in different places could interact to solve complex problems.

This had been Engelbart’s longtime passion since at least 1950. But he found little support in academia or among electronics firms, so he turned to the research world. His ideas eventually caught the attention of the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency, which gave him cash to organize his own lab at the Stanford Research Institute in Palo Alto, Calif.

His proposals were radical at the time: multiuser online systems, computer displays with multiple windows, software that could process typed words.

Oh, and a clunky hand device used to move a cursor around a computer screen. “Somebody saw that thing with that one button and said, ‘Oh, it looks like a one-eared mouse,’” he recalls.

Industry a late adopter

In 1968, he demonstrated his entire NLS (oN Line System) to a stunned crowd in a San Francisco auditorium. Impressive as it was, industry mostly shrugged. Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center opened in 1970 and soon had adopted similar concepts for the workplace. But Xerox was primarily interested in office systems to make secretaries more productive. Finally, in 1984, Apple put many of Engelbart's ideas — the mouse, the windows — into its new Macintosh.

“It seemed to me it was pretty good, because no one had come up with something that was more generally usable,” Engelbart says. But he still found it “terribly restrictive,” like trying to communicate in pidgin English, even after a Redmond, Wash., software maker took the idea and put it on most of the world's remaining computers. (Said company is a joint partner in MSNBC.)

All the while, Engelbart worked to advance the concept of hypertext — linking between and within documents — and to build out the ARPANet, the Internet’s precursor. His lab, acquired by McDonnell Douglas, was shut down in 1989; currently, he runs the Bootstrap Institute out of the offices of mouse maker Logitech, still focused on how to interactively solve complex problems.

Engelbart is often portrayed as visionary — “radical,” he suggests — but perhaps with a chip on his shoulder about the realities of modern commerce. He insists it’s not sour grapes.

Rather, he argues, firms are good at extracting profits from existing inventions, but not at inspiring new ones. While he acknowledges that the profit motive drives the economy, he dismisses corporate research’s ability to create things with real societal value: “We’ll get a better microwave oven out of it. But that’s not the way we get real evolutionary changes.”

And he has seen other innovations that incorporated his concepts — this little online medium you’re using right now, for one — emerge from the nonprofit research world, only for companies to later claim them as their own.

“You’d never be able to convince me that business prospects could’ve created the Internet or the World Wide Web,” Engelbart says.

Time for tinkering

Of course, some companies do set time aside for innovation. A key to Google’s corporate lore is its workers’ ability to use 20 percent of their time for their own projects. 3M allows engineers 15 percent of their time.

Fry used that time to keep pushing the Post-It concept until it finally stuck. The company still uses research fairs to promote the idea-sharing (“cross-pollination,” as Greg Anderson, a technical director at 3M’s office-supply division, calls it) that allowed Fry to find Silver’s adhesive. “The fortuitous moment isn’t so much of the ‘oops factor,’” Anderson says. “I think the fortuitous moment is when it comes together.”

Yet even Fry, now retired, feels companies have become less tolerant of tinkerers. He recalls how he used to, um, borrow leftover supplies and bring his own toolbox and computer into the lab.

In the modern corporate world, where everything needs ID tags and requisition forms, where metrics-minded CEOs focus relentlessly on lower costs and higher profits, fortuitous moments can be lost. “I’m very suspicious of a lot of what’s being done today, the search for high productivity,” Fry says. “There’s not time to look at the future.”

Wilson Greatbatch also finds little solace in corporate culture. Much of his 40-year career has been hinged on trying to stay a step or two ahead of the business model. And with 319 patents to his name — “more than any living inventor” -– he says he’d rather keep looking for novel technologies to help people. No longer part of his namesake company, medical technology firm Wilson Greatbatch Technologies, the 84-year-old inventor now uses his 20-person R&D firm, Greatbatch Enterprises, to explore everything from HIV research to helium fusion reactions.

Greatbatch worries about Wall Street’s inability to find value in intellectual resources, and the one-time Navy aviator sees little public commitment to funding for technical education like the GI Bill, which got him his engineering degree.

Perhaps most importantly, he believes, we’ve become far less tolerant of failure — which helps inventors learn to succeed. After all, the Biro brothers went through plenty of failed prototypes to perfect the ballpoint pen. And it might be for the best that Thomas Edison’s concrete piano never caught on.

“Failure’s a learning experience, and the guy who’s never failed has never done anything,” Greatbatch says. “Nine out of 10 things I’ve done have never worked. And that doesn’t bother me.”