Aerospace giants are already prepared to compete for lucrative contracts in NASA’s next big step toward the moon and Mars, but they aren’t eager to start from scratch on a new rocket to take it there.

Rather than a crash program to produce a new super-rocket, like the Saturn 5 moon rocket in the 1960s, this new initiative — which NASA is a year or more away from detailing — is more likely to use existing technology from space shuttles and expendable rockets.

That was the word from industry representatives attending the 41st Space Congress this week in Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Boeing and Lockheed Martin representatives say their companies are both looking at new, or “clean sheet,” rocket designs — but they agree that the cost of building new systems from scratch, including the manufacturing plants and launch facilities that would be needed, might prove prohibitive.

“Clearly, one of the challenges is to make sure there’s money left for space exploration after you’ve built a launch vehicle,” said Michael Gass, vice president for space transportation at Lockheed Martin.

Modified Deltas and Atlases?

One of the main points of the proposal President Bush announced in January was that this initiative, unlike the Apollo program, would move forward with only small, stable increases in NASA’s annual budget.

The early years will be the leanest. While the space shuttle is still flying and the international space station is still under construction, they will continue to eat up most of NASA’s budget.

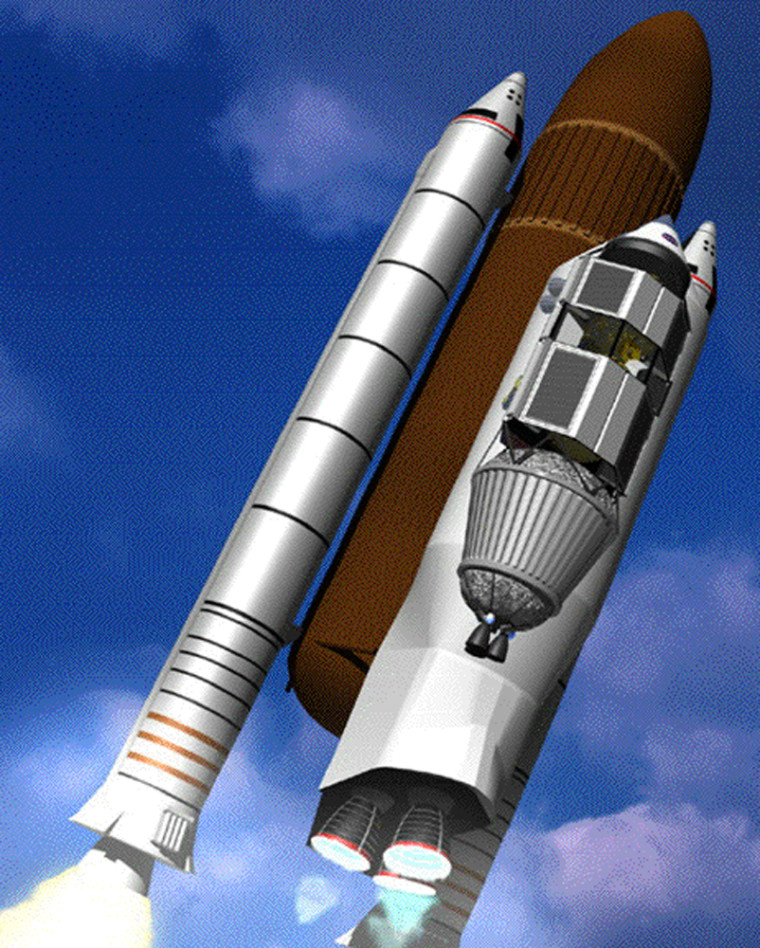

Both Boeing and Lockheed are looking at their new generations of expendable rockets, Boeing’s Delta 4 and Lockheed’s Atlas 5, to see if they can be modified for the job.

The problem is that both rockets were developed under U.S. Air Force contracts for putting satellites into orbit. Launching humans, or even heavy cargo, into interplanetary space would require extensive modifications to both the rockets and their launch facilities.

Reconfiguring the shuttles

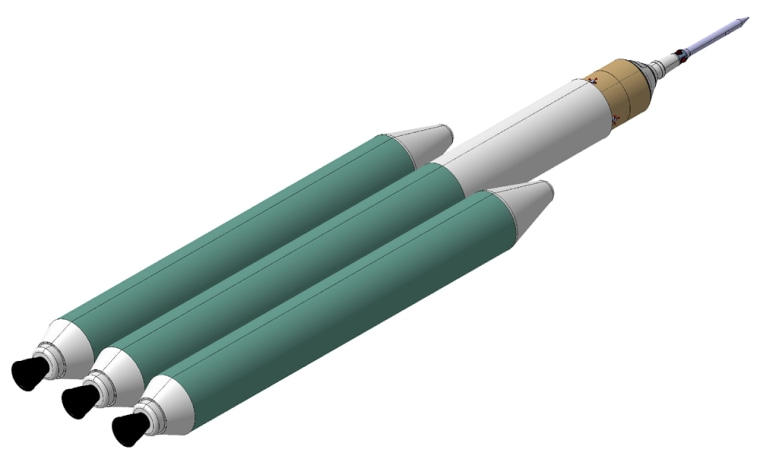

Both companies, along with ATK Thiokol, a unit of Alliant Techsystems Inc., also have teams at work on how space shuttle systems might be reconfigured for the job.

The advantage there is that the massive Vehicle Assembly Building at Kennedy Space Center, one of the largest buildings ever erected, and the shuttle’s two launch pads are already in place and would continue to be used, along with the engineers and technicians who have worked on the shuttles for years.

“We have to take full advantage of what we have today. How do we leverage what we already have, what we already know, what we can already do?” said Mike Khan, an ATK Thiokol vice president.

The official report on the fatal crash of the shuttle Columbia last year called for retiring the shuttle fleet as soon as possible, but as Khan, Gass and others made clear, the aging orbiters themselves would not be used. Instead, a cargo fairing would be bolted to the same place on the fuel tank.

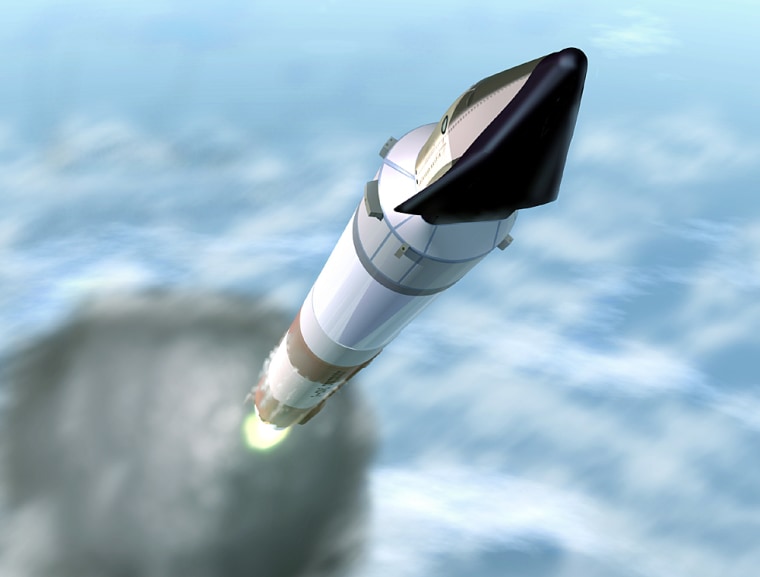

For human launches, a new second stage would be built and mounted on top of the fuel tank, with the crew capsule on top of that, so the configuration would look much more like a traditional rocket.

Another advantage to modifying existing rockets or shuttles is that they would fly much sooner than a new rocket. Industry representatives all warned that prolonged development could cause the public to lose interest.

“We think that might be the way to go. Get some early successes without trying to hit the home run. A few good singles up the middle to get the momentum going and get support behind the program,” said Dan Collins, Boeing’s Delta program manager.