Perhaps it was a sign of things to come. Earlier this month, bright flashes in the sky had heads turning. Sure, it turned out to be a meteor, but then what to make of that green creature seen perched atop the Space Needle?

Yes, aliens had come to Seattle.

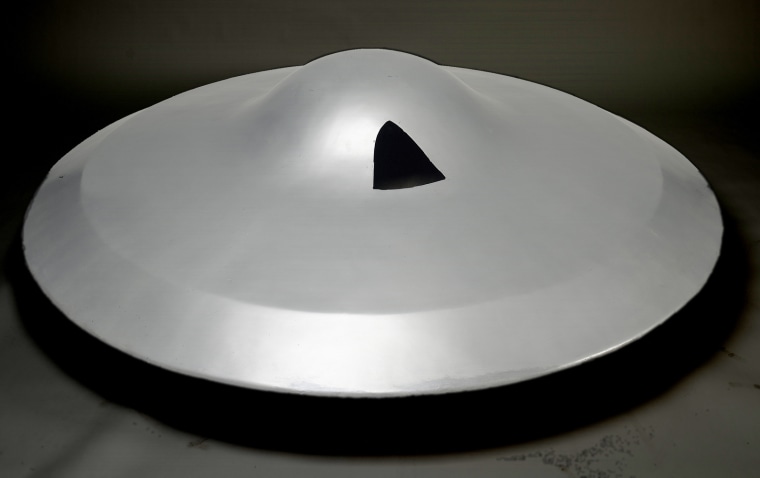

The Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame, which opens Friday, features the usual intergalactic suspects — E.T. and Yoda; the robot B9 from “Lost in Space” (“Danger, Will Robinson!”); and Robby the Robot of “Forbidden Planet” fame. Captain Kirk's original chair from the U.S.S. Enterprise is here — as well as other more obscure artifacts, from the crossbow used by Jane Fonda in her 1968 sci-fi foray “Barbarella” to a Buck Rogers XZ-38 disintegrator pistol, circa 1936.

The new venture has a worthy ancestor: The Acker Mansion & Museum, based in Los Angeles, and home to more than 400,000 items situated in an 18-room mansion in the Hollywood Hills.

The Seattle museum is meant to be more than just a pop-culture garage. For all its fanciful aspects, the museum succeeds in achieving one of its prime directives: to educate, showing the ways science fiction often becomes science fact, predicting evolutions in technology years before the evolutions actually happen.

The 13,000-square-foot museum is housed in the Frank Gehry-designed Experience Music Project building; both projects were the brainchild of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, a longtime science-fiction fan who contributed $20 million and more than a few artifacts from his family collection.

Walking through the museum space, you're caught up in the whoosh and flash and thump of serious sensory overload. The numerous exhibits point up the close relationship between today's technology and its fictional antecedents: Flip open your cell-phone and hold it next to one of the communicators from the “Star Trek” TV series from the mid-60's. The future of telephony was calling back then; can you hear it now?

Sci-fi as inspiration

“From early on, we thought we'd have to tell the whole story," said Greg Bear, a Hugo- and Nebula-award winning science fiction author, and the chairman of the museum's advisory board.

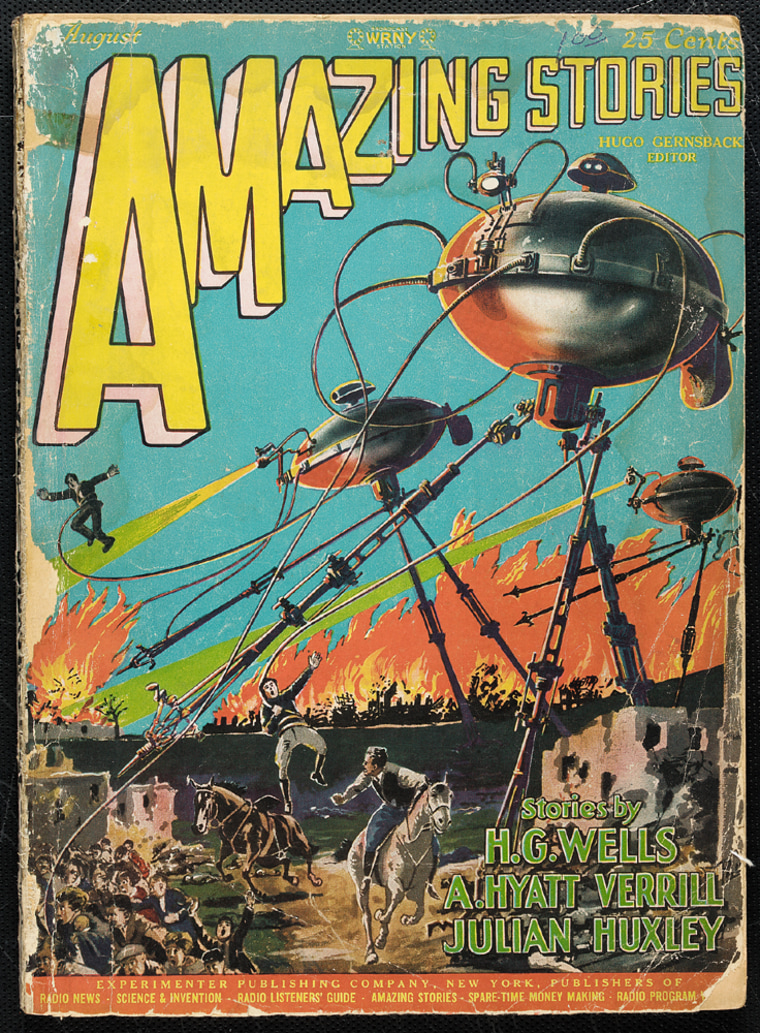

"That means you take key artifacts — those you could get — and put them on display, everything from books and magazines to films. You interview authors, filmmakers, the creative minds and talk about what inspired them. And you put scientists into the mix. Put all that together and you've got a fabulous story, one that hasn't been told before.”

Leading the effort to tell that story is museum director Donna Shirley, a former Jet Propulsion Laboratory engineer who directed the Mars Sojourner exploration program. The advisory board is a who's who of science fiction: Ray Bradbury, David Brin, Octavia Butler, Orson Scott Card, Freeman Dyson, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and many more.

“Science fiction and science go together pretty much hand in hand,” Bear said.

“We know that a lot of scientists, if not the majority, have read science fiction as youths and were inspired by it, not necessarily to go into their chosen careers but just to think about change, think about new ideas, and to become radicalized in the notion that the universe is never standing still, and is never what you expect.

“The whole world is changing all the time; you can't step in the same river twice. That's what science fiction teaches us from a very early age. It immunizes us against future shock; we aren't going to be too stunned by the changes in the future, because we know that was going to happen or something like it.”

Da Vinci to Jules Verne

Jules Verne (1825-1905) is often named as a sci-fi founding spirit; so is Mary Shelley, who published “Frankenstein” in 1818. But the museum's historical timeline suggests that science fiction goes even further back.

Consider the timeline's inclusion of Leonardo da Vinci's design for what would become the helicopter — a design dating from 1500. And then there's Sir Thomas More's “Utopia,” a book from 1516 whose vision of an idealized society preceded other brave new worlds in literature and film.

Other early adopters?

“There are books from ‘Somnium’ [astronomer Johannes Kepler’s posthumously published 1634 novel of a voyage to the moon] going back to the Iliad, which had a bronze robot in it,” Bear said. “If we go back that far, we have the technological imagination. That sort of science fiction begins to show some signs of what it would later become.”

Unfortunately, a thing of space-age beauty isn't necessarily a joy forever. One of the museum's biggest challenges, ironically, is keeping its futuristic treasures from falling apart.

“Anything made out of foam rubber is going to rot away within three to four years,” he said. “You're looking at artifacts, a lot of the creatures on display. I've got artifacts from the 1970s that are [in such poor condition that] that you have to put them in [liquid] helium or they'll rot away. It’s the same with pulp magazines and first-edition books. ... You buy one of those from an old pulp-magazine house and you could have it crumble in your hands. Magazines from the 1950's are in pretty rough shape; it's the paper they used.

“Conserving that, keeping that heritage intact in real form, is a difficult job.”

That other difficult job — telling the “whole story” Bear spoke of earlier — isn't over, either.

“We've only got 13,000 square foot here,” he said. “How do we cover the entire history of 200 years of science fiction in 13,000 square feet? We could fill a hundred thousand square feet! So, down-the-road is not planned out yet, but it's being thought about.”