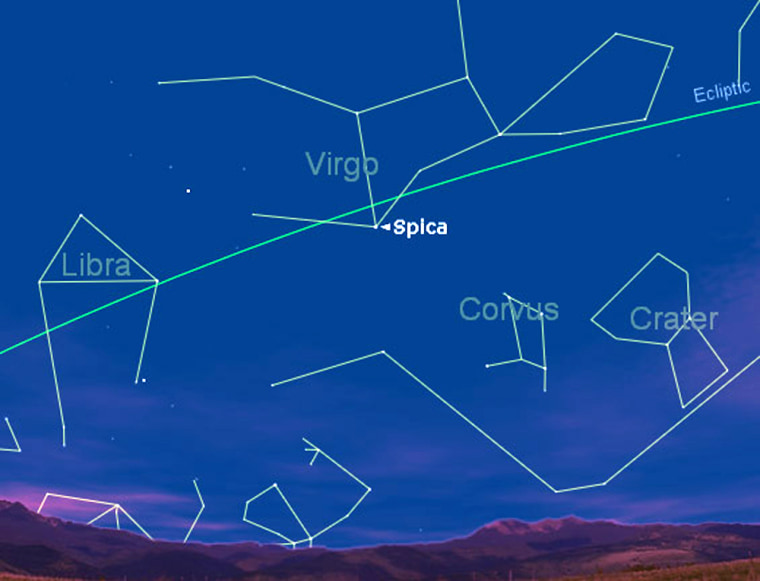

Avid skywatchers know spring is well advanced when the star Spica appears almost due south at dusk. Indeed, with summer set for its official arrival in the Northern Hemisphere on June 20 at 8:57 p.m. ET, Spica is located within the large dim region of the constellation of Virgo.

Virgo is a dull star pattern that owes its importance mainly to its location within the zodiac, but Spica is its gem. The star is visible even amid the glare of city lights.

Virgo is supposed to represent Astraea, daughter of Zeus and Themis, the personification of the goddess of justice who was the last of the deities to abandon the earth at the end of the fabled Golden Age.

Spica is the only conspicuously bright star in Virgo. A bluish-white star of great luminosity, Spica is so far away that its light requires 262 years to travel across the vast gulf of space that separates it from Earth.

Since light travels at 186,282 miles per second (299,791 kilometers per second) it is obvious that Spica must be far brighter than our sun but tremendously farther away. Indeed, it’s a brilliant "helium"-type star, about 2,300 times more luminous than our sun.

Star of the first magnitude

Spica ranks as the 16th-brightest star in the night sky and can be regarded as a nearly perfect example of a star of the first magnitude. On the magnitude scale, brighter stars are noted with lower numbers, with negative ratings reserved for the very brightest objects, including the moon and some of the planets. Stars dimmer than about magnitude 6 or 6.5 can't be seen without binoculars or telescopes.

As listed in the 2004 Observer’s Handbook of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Spica's magnitude is given as 0.98, though the star actually varies slightly at irregular intervals from 0.97 to 1.04. It has a tiny companion — invisible even to powerful telescopes — that astronomers discovered while analyzing its light with a spectroscope back in the year 1890.

The name Spica comes from the Latin "Spicum," and is said to signify a spike or ear of wheat. It is derived from the ancient allegorical drawings of the goddess, whose figure was somehow traced around the scattered stars by the imaginations of primitive stargazers. In many parts of the classical world she was the "Wheat-Bearing Maiden" or the "Daughter of the Harvest."

The goddess was shown holding several spears of wheat in each hand, and Spica is in one of the ears of grain hanging from her left hand, evidently representing the harvest time that occurred when the sun was passing this bright star. Interestingly, in another legend, Virgo supposedly represented Persephone, daughter of the goddess of the harvest, Ceres, and as such is associated with agricultural matters.

The only astronomy reference that goes against the grain as to where Spica is located is in the famous guidebook "The Stars: A New Way to See Them" by the late H.A. Rey (1898-1977). Rey pictured Virgo lying on her back and stretched out along the ecliptic, the imaginary arc across the sky along which the sun, moon and stars track as seen from Earth. As for Spica, Rey referred to it as Virgo’s brightest jewel, but located "on an unusual spot."

Stargazers' favorite

Henry M. Neely, who passed away in 1963, was known as "The Dean of New York Stargazers" and lectured until he was well into his 80s at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. When pointing out various objects during a typical planetarium lecture, Spica was among his favorites. Back in the 1950s, Neely would often train his electric arrow-pointer on Spica and remark:

"Spica could have been totally destroyed at the time of the signing of our Declaration of Independence, yet men would still be seeing it shining serene and undisturbed in its accustomed place until the babies who are now in their mothers’ arms are aged men, cursing their rheumatism and the younger generation in the same breath."

Considering that the light that left Spica back in 1776 still has another 34 years to reach us, perhaps it will cause those baby-boomers born during the 1950s and who gaze at Spica on a late spring night this year to pause and reflect on Neely’s prophetic words.