When the senior al Qaeda planner of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks wanted to drop a hijacker from the plot because he was ignoring his training, the boss overruled him.

When he wanted to expand the plot to the West Coast and even into Asia, the boss said no.

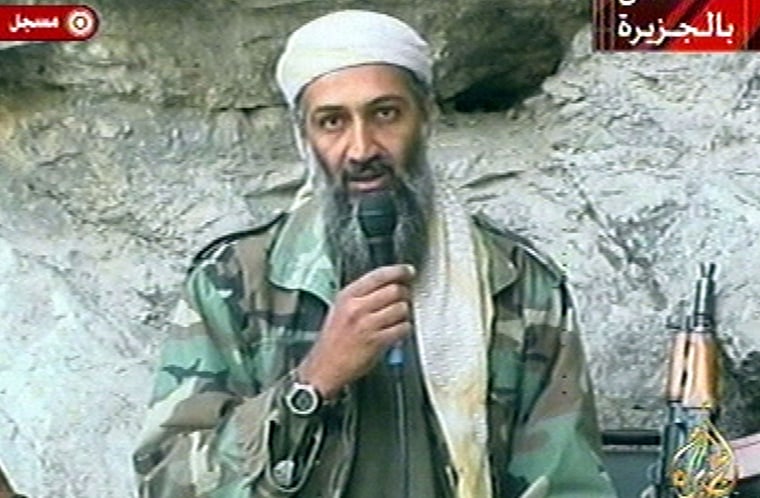

And when other al Qaeda leaders expressed eleventh-hour reservations about striking the United States using passenger jets as missiles, the boss — Osama bin Laden — bulled through the opposition and gave the fateful green light.

This portrait of the terrorist-as-CEO emerges from a chilling report released yesterday by the commission investigating the attacks and is based on interrogations of captured bin Laden associates. Although the report cautions that some evidence is contradictory, the document nevertheless provides the most detailed glimpse yet of bin Laden's management of his war on America and of tensions inside his al Qaeda as the group undertook its most brutal project to date.

The bin Laden revealed by his associates is a hands-on leader, a prod at times and a brake at others, aggressive, audacious — but not reckless within the warped framework of his murderous enterprise. He has a knack for choosing the right men for a job and demands from his inner circle an oath of loyalty directly to him. The planning and execution of the strikes on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were steered by bin Laden through a process that might be familiar to business executives the world over.

"It does have a corporate quality about it," said Brian Jenkins, a Rand Corp. terrorism expert. "Different individuals specialize in different areas, with bin Laden appearing to be personally involved. He is not just a mouthpiece. . . . He comes across, in this particular account, as a leader reviewing proposals, putting some on the shelf, moving others into the feasibility study phase. He's thoughtful, ambitious, cold-blooded, willing to take enormous risks but at the same time scaling things back to be sure that he succeeds."

A match made in hell

The report also details, in spare yet heartbreaking detail, how many times and ways the plot might have gone off track. The original scheme was half-baked, the original hijackers were feckless, bin Laden was at one point willing to settle for a much weaker blow if only he could have it sooner. A key operative appeared to get cold feet. Bin Laden's Taliban allies argued against the attack.

Yet it happened. The killing of nearly 3,000 people began as a perverse twist on an everyday transaction: a pitch from a man with a big idea to a man with the resources to make it happen.

In early 1999, bin Laden was an impresario of global terrorism looking for a bold new plot. Khalid Sheik Mohammed had a terrible vision but needed men and money. Their meeting in the Afghan city of Kandahar was a match made in hell.

This was their second such encounter. Mohammed, a veteran anti-American terrorist, had approached bin Laden in 1996 with a proposal that blended his two obsessions: the World Trade Center and exploding airplanes.

With his nephew and others, Mohammed had tried in 1993 to destroy the twin towers. His attempt to bomb a dozen U.S. jets in flight — simultaneously — had recently been foiled by police in the Philippines.

At that first meeting, bin Laden "listened, but did not yet commit himself," the report said.

But a lot changed between 1996 and 1999. Bin Laden was forced from his cozy base in Sudan to a dangerous refuge in Afghanistan. Bouncing back, he helped the Taliban take control of the country and merged his group with the Egyptian Islamic Jihad. On Aug. 7, 1998, al Qaeda pulled off its deadliest strike yet, the bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. President Bill Clinton ordered cruise missile strikes on an al Qaeda camp in retaliation.

Bin Laden "summoned" Mohammed to Kandahar, according to the report. Al Qaeda's chief operating officer, Muhammad Atef, also attended. They told Mohammed that his plan "now had al Qaeda's full support," starting with four potential suicide bombers "so eager to participate in attacks against the United States that [two of them] already held U.S. visas."

Lacking in motivation

Those two — Nawaf Alhazmi and Khalid Almihdhar — began training for the plot in the fall of 1999, and in January 2000, they were the first conspirators to enter the United States. The other two initial hijackers could not obtain visas, so Mohammed proposed deploying them in a coordinated attack in Asia. Too complicated, bin Laden ruled.

Alhazmi and Almihdhar were supposed to learn English and enter flight school, but they seemed to lack motivation. Mohammed "was displeased and wanted to remove [Almihdhar], but bin Laden interceded" on behalf of his Saudi countryman, the report said.

But by then, at his Afghan training camps, bin Laden had found better prospects for the plot: four young men from Germany, including Mohamed Atta, whom he named emir — leader — of the operation in the United States. One of the four, Ramzi Binalshibh, failed to secure a visa, and became the communications link between Atta and the al Qaeda hierarchy. The other three entered American flight schools.

Bin Laden's attention to detail never failed, according to the report. From the thousands of would-be jihadists pouring into his training camps, he culled the eventual pilot of the Pentagon-bound airplane, Hani Hanjour, and the 14 "muscle hijackers" who would seize the planes and control the passengers. He pressed for a strike on the White House, pushing repeatedly in the spring of 2001 to speed up the plot to take advantage of a visit to Washington by Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon.

Bin Laden sent the man who may have been a backup terrorist, Zacarias Moussaoui, to get flight training in Malaysia in 2000. (Moussaoui, Binalshibh and Mohammed are in U.S. custody, along with other key al Qaeda leaders.) In the end, it was bin Laden who gave the word to strike. He "argued that attacks against the United States needed to be carried out immediately," the report said. "In his thinking, the more al Qaeda did, the more support it would gain . . . and the attacks went forward."