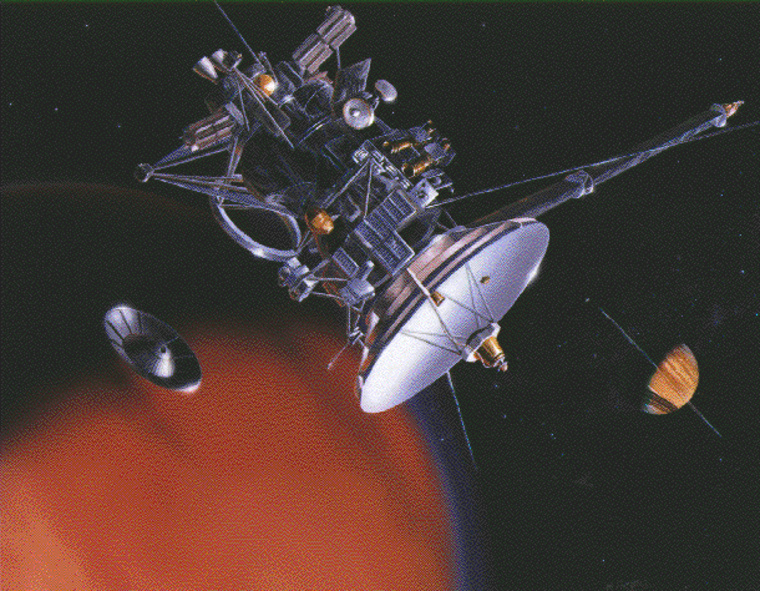

Two decades and $3.3 billion in the making, an international exploration of Saturn begins this week when a spacecraft slips through a gap in the planet’s shimmering rings and arcs into orbit.

After a seven-year, 2.2 billion-mile (3.5 billion-kilometer) journey, the Cassini spacecraft will fire its engine Wednesday night to slow down, allowing itself to be captured by Saturn’s gravity. The maneuver will inaugurate a four-year, 76-orbit tour of the giant planet and some of its 31 known moons, including huge Titan.

To scientists, Saturn and its rings are a model of the disk of gas and dust that initially surrounded the sun, and they hope the mission offers important clues about how the planets formed.

Shortly after entering orbit, Cassini will act on its best chance to photograph the rings that have entranced astronomers for centuries.

“We’ll never be that close to the rings as immediately after the insertion,” said Charles Elachi, director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and team leader for Cassini’s radar instrument.

Cassini, laden with a dozen instruments, also carries a probe named Huygens that will be launched into the murky atmosphere of Titan.

The frozen moon intrigues scientists because it may have many of the chemical compounds that existed on Earth before life began.

Joint NASA-Italian-European project

Named for 17th century Saturn observers Jean Dominique Cassini and Christiaan Huygens, the joint project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency dates back to proposals made in 1982.

Many of the project’s 260 scientists have spent years just planning the mission, building Cassini at JPL in Pasadena and getting the spacecraft out to Saturn.

“We received our letters of acceptance of being team leaders or team members almost 15 years ago,” Elachi noted at a briefing this month. “So as you could imagine my colleagues have great anticipation.”

The show has already begun

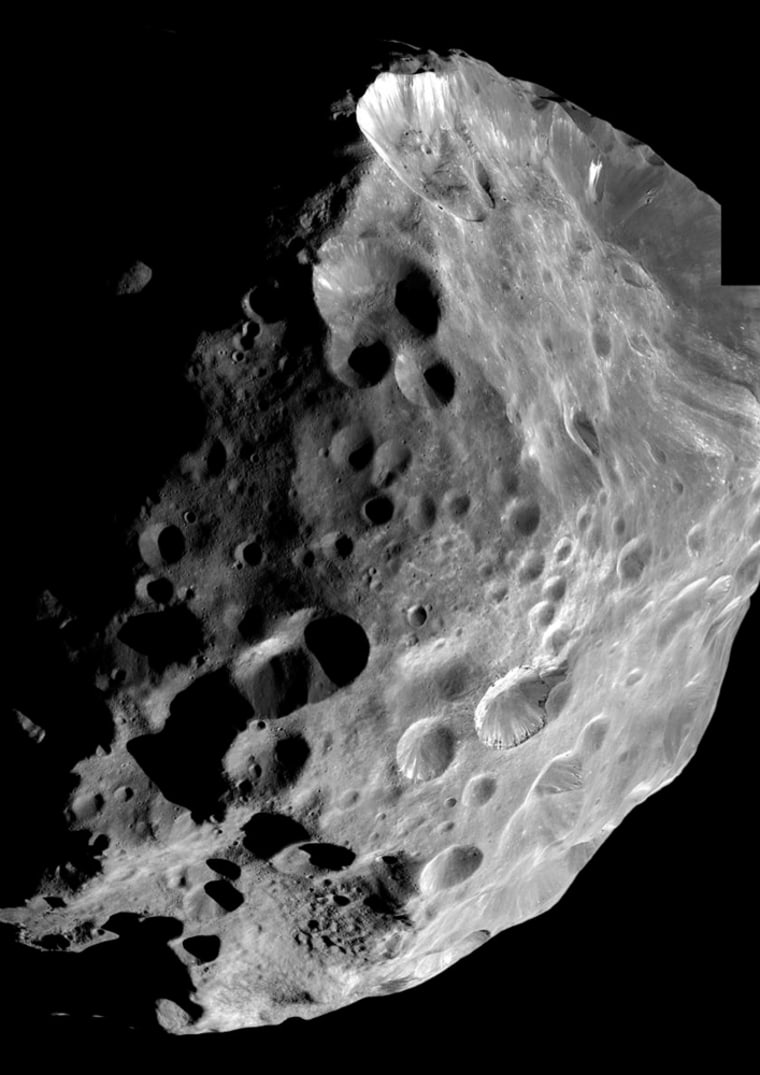

Cassini has already been sending data to Earth, including a wealth of information and sharp images from a close flyby of Saturn’s strange, battered old moon Phoebe.

“It’s a great curtain raiser for the Saturn show that’s about to start at the end of the month,” JPL imaging team member Torrence Johnson said.

Cassini is 22 feet (6.7 meters) long, 13.1 feet (4 meters) wide and weighed nearly 12,600 pounds (5,700 kilograms) loaded with fuel and the probe. Too far from the sun to rely on solar panels, it uses plutonium-fueled radioactive generators to provide electricity.

People who worried that an accident could release nuclear material protested Cassini’s Oct. 15, 1997, launch from Cape Canaveral, Fla. There was more concern when Cassini made a 1999 Earth flyby, but all went as planned.

What Huygens will do

The wok-shaped Huygens probe, developed by the European Space Agency, will be released from Cassini in December and will enter Titan’s atmosphere in January.

Just under 9 feet (2.75 meters) in diameter and weighing 705 pounds (320 kilograms), its six instruments will investigate Titan’s atmosphere and then its surface, if it survives the impact of landing after a 2½-hour descent by parachute.

It may not find a hard surface, however, and instead splash down into liquid methane or ethane, which would quickly shut down the probe.

The probe will radio data back to Cassini up to a maximum of 30 minutes after touchdown. By then, either its batteries will have failed or Cassini will have passed over Titan’s horizon.

In 2000, mission officials discovered a problem that would have prevented Cassini from receiving most of that data. The design had not accounted for the Doppler effect, which will change the frequency of the transmissions as Huygens falls through the atmosphere.

Jean-Pierre Lebreton, ESA’s Huygens project manager, assured reporters earlier this month that the problem was fixed. But he said testing would continue until scientists were sure.

Implications for Earth's history

According to Elachi, some scientists believe Titan has a “pre-biotic” environment in which there is organic, or carbon-based, chemistry, but the surface temperature of minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit is inhospitable to life.

“In a sense it will give us a past picture of our own planet before biology got started,” he said.

Saturn will be some 930 million miles from Earth when Cassini arrives. Radio signals will take 84 minutes to travel each way, so the spacecraft will enter orbit on autopilot.