The ancient Romans built seven major highways, two of which made a beeline south to key ports at the stiletto heel of Italy’s boot. During the Middle Ages, pilgrims and Crusaders used the roads on treks to the Holy Land. These days, most travelers head to the region known as Apulia (Puglia, to Italians), only to hop a ferry bound for the Greek Isles. By scurrying straight along to sun and fun in Greece, they’re missing out on the most wonderfully weird corner of Italy. Amid rolling, sun-soaked landscapes is a wild mix of architecture: cone-shaped roofs, entire towns carved into hillside caves, ancient villages all in white, and a city of baroque treasures adorned with dragons, Harpies, and other fantastical creatures. And although it may seem like the stuff of fairy tales, Apulia remains authentic and overlooked by the crowds.

Alberobello: Trulli remarkable

The Valle d’Itria is a storybook Italian landscape—stone walls dividing lush farmland into patchwork fields. Look closer and you’ll see that, instead of standard farmhouses, many buildings are trulli: cylindrical homes of whitewashed limestone with conical roofs of stacked, dark-gray stones.

Some say trulli were built that way so that peasants could pluck out a stone—and cave in the roof—whenever they saw the king’s men coming, because “unfinished” structures couldn’t be taxed. Others maintain that this was simply one of the easiest ways to put a roof over your head without using mortar. Whatever the case, they keep their owners cozy in the winter and cool during the baking summers.

With more than 1,400 of the beehive buildings in two separate neighborhoods, Alberobello is truly trulli central. It’s also where you can try one out for the night. About a decade ago, local entrepreneur Guido Antonietta bought a few dozen abandoned trulli and installed modern kitchenettes, chunky wooden furnishings, and cast-iron bed frames. He even revived the ancient custom of painting a Paleo-Christian good-luck symbol on the roof. “I was always a little different,” says Antonietta, who recalls insisting on being the lone Indian when he played cowboys and Indians as a child in the alleys of Alberobello. His company, Trullidea,(Via Monte Nero 15, Alberobello, 011-39/080-432-3860, trullidea.it) rents the one-room homes for $95 to $112 per night, less than what some nearby hotels charge.

So what do you do in your trullo? First, open the shutters on the deep-set window to let some light in on the stone floors. Like the outside walls, the interiors are slathered in whitewash, even on the inside of the stone roof, though that’s usually blocked off by a ceiling of wooden planks. Bathrooms and kitchens are tiny but usable, and shops are never more than a few blocks away.

Then take a cue from the locals. Up and down Alberobello’s steep streets, you’ll see women stationed in doorways, sitting in cane-bottom chairs. They keep their hands busy—shelling peas, mending dresses, crafting toy trulli for their sons’ souvenir shops—while chatting with their neighbors, each perched in her own doorway. (Italian men, on the other hand, traditionally congregate in public places—at the local bar, on a roadside bench, or in the piazza.) Follow the ladies’ lead and drag a cane-bottom chair into your own doorway. Your only chore is to while away the afternoon, soaking up the sun and maybe reading.

Although trulli are still sprinkled throughout the Valle d’Itria, the majority of architecture outside Alberobello is modern in a boring way. An exception is the area along an unnamed back road linking Alberobello with the town of Martina Franca. It’s frozen in the Apulia of ages past, blanketed with olive groves, vineyards, and hundreds of trulli. The road is a devil to find, though: Do not follow the signs toward Martina Franca from Alberobello’s center. Instead, follow signs to Locorotondo, and, as you leave Alberobello behind, look on the right for a white sign pointing to Agriturismo Greek Park. That’s the road. It’s narrow, fenced in by stone walls—scary when you meet the rare oncoming car—and it cuts right through the hidden heart of the Valle d’Itria.

At some point, do continue down the main road to Locorotondo, a hill town of concentric streets lined with whitewashed buildings. Locorotondo’s nickname is “the balcony on the Valle d’Itria” because of its stunning valley views. Within Italy, Locorotondo is even better known for its wine. The region of Apulia is Italy’s most prolific wine producer, churning out 17 percent of the national total. For centuries, it was just the grapes that interested the world’s wine industries. Turin imported them to make vermouth, and France would sneak them into their presses during bad harvest years. But Apulian wine now trades on its own merits, getting press in culinary magazines and showing up in U.S. wine stores. Robust, structured reds, such as Primitivo and Salice Salentino, are as rich and complex as anything you’ll find in Tuscany, but they start at around $7 per bottle, a fraction of what you pay for wine of similar quality in Florence. A standard table wine in Apulia costs less than $3. For free tastings (and cheap bottles), head to Locorotondo’s Cantina Sociale (Via Madonna della Catena 99, Locorotondo, 011-39/080-431-1644) a wine cooperative made up of more than 1,000 local vintners.

The raw earthiness of even Apulia’s younger reds partners perfectly with the strong flavors of local cooking, where stewed meats are a staple. In Locorotondo, try Giovanni Loparco’s homey Trattoria Centro Storico (Via Eroi di Dogali 6, Locorotondo, 011-39/ 080-431-5473) the locals’ preferred lunch spot, kept cool by thick stone walls (important when southern Italy’s powerful sun is out). Try the house pennette, a quill-shaped pasta in a hearty tomato sauce spiked with hot peppers, onions, and chunks of ham, or Giovanni’s signature portafoglio—a “wallet” of lamb chops stuffed with cheese, parsley, and wild herbs.

For an even more memorable meal, drive 15 miles east, up a 715-foot hill, to Ostuni. Known as the White City, Ostuni is a spiral of buildings layered with so much whitewash that they look sculpted from meringue. Inside one is Osteria del Tempo Perso (Via G. Tanzarella Vitale 47, Ostuni, 011-39/0831-304-819.) The front room is decorated with watercolors of Ostuni scenes, dozens of old farm tools, and, hanging in an alcove, an antique bicycle. Deeper inside, past pendulums of cured meats and garlands of garlic and red peppers, is a candlelit dining room in a cave that was carved out of bedrock 500 years ago. Stacks of colorful fruits and vegetables surround a central column; the chef occasionally pops out of the kitchen to pluck a few for his recipes. Sit at one of the thick wooden tables and, even before you receive a menu, the waiter drops off a dozen tiny plates laden with antipasti: stuffed mushroom caps and frittata wedges, falafel and steamed tripe, roasted vegetables in olive oil, and cheeses stuffed with other cheeses. For the main courses, try Apulia’s Frisbee-shaped orecchiette pasta under a tomato sauce speckled with salty cacioricotta cheese or topped with bitter turnip greens laced with spicy pepperoncini. If there’s still room, go for the arrosto misto, a platter of roasted sausage, lamb, and liver.

Work off the feast by wandering through the White City’s maze of alleys, which are too narrow even for Italy’s minuscule cars. Peek between buildings for views over terraced vineyards and olive groves to the Adriatic Sea, less than four miles away.

Matera: The Cave City

There are cavemen in Italy, thousands of them. Cavewomen, too. They’re the people of la civiltà rupestre, a “cliff civilization” that inhabits the instep of Italy’s boot. For millennia, they carved cities directly into ravines and gullies made of tufa, a soft, porous stone that’s easily cut and molded, then quickly hardens upon exposure to the air.

These days, the people of la civiltà rupestre have slapped front-room facades onto their cave entrances, turning the tightly packed city centers into jumbles of houses stacked willy-nilly atop one another. Despite the squared-off front rooms, satellite dishes, and a few other signs of modern life, the homes inside are bona fide caverns.

When Italy drew up its regional boundaries 140 years ago, Apulia’s border sliced through this ancient culture. Most cave cities are in Apulia, including Ginosa, Massafra, and Móttola. But Matera, the most dramatic, lies five miles across the border in Basilicata.

Up through the World War II era, some 15,000 people lived without electricity or running water in cave homes in Matera, a city built into two parallel ravines separated by a high ridge. In the 1950s, the population was relocated en masse to a modern town on a plateau, just above the ravines. The old town, abandoned by all save a handful of the most destitute squatters—who caught rainwater in discarded washing machines and planted meager gardens in old bathtubs—became known as La Città Fantasma.

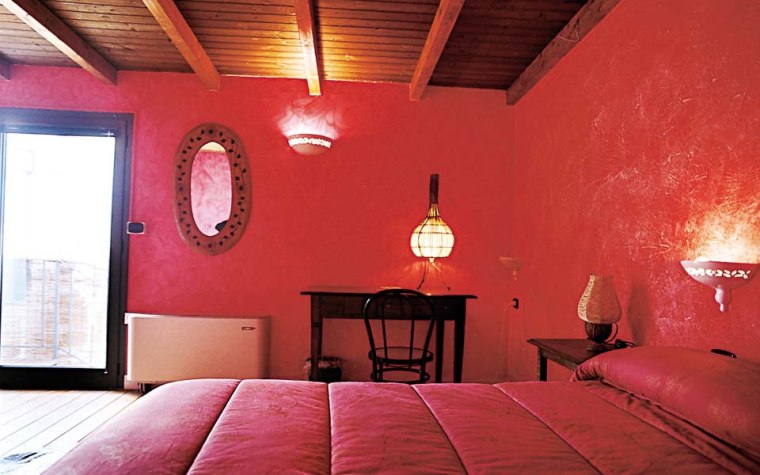

The Phantom City has risen from the dead: Revitalization efforts over the past decade have brought electricity, plumbing, and, slowly, the people into the old cave neighborhoods, known as i sassi (“the rocks”). In 1998, Raffaele and Carmela Cristallo bought a string of homes in the part of town known as Sasso Barisano and converted them into the Hotel Sassi (Via S. Giovanni Vecchio 89, Matera, 011-39/0835-331-009, hotelsassi.it, $95–$110.) You can’t go wrong with any of the 22 rooms, even if only three are full-fledged caves. Most have at least one wall of raw, honey-colored bedrock. The rooms with only modern walls have balconies blessed with panoramas of the Barisano, a particularly romantic setting at night, when warm yellow floodlights shine on the city.

Another entrepreneurial pair, Umberto Giasi and Eustachio Persia, took a vast cavern underneath the modern town, slapped the rough walls with whitewash, and started serving pizza and Apulian dishes to hungry crowds. They called the joint Il Terrazzino (Vico S. Giuseppe 7, Matera, 011-39/0835-332-503) because of its narrow terrace with views of the Barisano.

Over the ridge from Sasso Barisano is Sasso Caveoso, the more rugged and untouched of the two cave-riddled ravines. When fixing up the sassi, Matera’s town fathers left the far southeast end of the Sasso Caveoso alone. This decision paid off in 2003: Mel Gibson chose Matera—and this neighborhood in particular—as the perfect stand-in for ancient Jerusalem in The Passion of the Christ. Many people spend an entire day wandering the Caveoso, in part because they keep getting lost in the maze of alleys, stairs, dead ends, and blind courtyards.

The cave churches ($4 each, or four for $6) scattered throughout the neighborhood are a big draw. Ten years ago, you needed to find someone with the keys and a flashlight for a look at the complex of a half-dozen churches known as the Convicino di San Antonio. These days the doors are thrown open and there are wooden walkways to guide you through the tiny, interlinked chapels. It’s still an eerie experience—you walk down steep tunnels into dark, cramped sanctuaries. In the chambers above, sunlight streams through windows bored through the rock, revealing delicate medieval frescoes.

Even more dramatic is the church of Santa Maria de Idris, carved into a huge rock pinnacle jutting from the lip of a gorge. Cave homes barnacle the lower reaches of the pinnacle, and a broad staircase continues above them to a terrace in front of the blank masonry facade of the church. Inside is an assortment of caves, spooky tunnels, and paintings on the rough tufa walls.

Lecce: Arts, Crafts, and Baroque quirks

Lecce is a town of traditional craftsmen and virtuoso chefs, and its university lends the place a youthful, cultural edge that’s missing from other Apulian cities. In the evening, throngs stroll past baroque churches and palazzi, crowd the sidewalk tables that spill out of every café, and pass the time in animated conversation until the 9 p.m. dinner hour.

Not everyone is out and about. A community of Benedictine nuns—locals simply call them Le Suore (“the sisters”)—lives a cloistered existence in the 12th-century convent of San Giovanni Evangelista on Via Manfredi. Although you’re never allowed to see the sisters or meander around their convent, you can play a kind of culinary Russian roulette with them. Le Suore are almost always selling something to eat, though precisely what changes daily. Ring the bell at the door and a feathery old woman’s voice crackles over the intercom, inviting you in. The bare front room looks like a bank counter, but with a solid wall instead of bullet-proof glass and a lazy Susan in place of a teller’s window. No one will appear, so you have to talk to the lazy Susan. Ask whether they have biscotti di pasta di mandorle—soft marzipan cookies with pear jelly in the center. A tray of 12 costs around $7. Then again, they may be selling raw fish that day; you never know. (That the sisters speak only Italian makes the game even more interesting.)

If you’d rather know what you’re buying up front, visit the Mostra Permanente dell’Artigianato (Via Rubichi 21, Lecce, 011-39/0832-246-758,) a showcase for artisans from across the region. Inside a large, bland room are brilliant, hand-painted ceramics, wrought-iron candlesticks, stone carvings, and other handiworks. And, since this is a city-run enterprise, there’s no markup.

The sole craft in short supply at the Mostra Permanente is the one that Lecce has been famous for since the 17th century: cartapesta, or papier-mâché. Lecce’s workshops do a brisk business cranking out life-size saints, crucifixions, and crèches for churches around the world. Artisans are at work all over town, and watching one can occupy an afternoon. First, they mold wet sheets of paper around giant, featureless mannequins made of wire and straw, then they stand the rough statues in the street next to a coal-stoked brazier. Iron rods are shoved into the coals until they glow, at which point the maestro plucks one out and uses it to burn delicate details into the clothing and faces. Every time he touches the red-hot iron to the figure, it sends up licks of flames and billows of smoke, not unlike scenes of hell so popular in medieval mosaics. The charred bodies begin to look holy only after thick layers of paint have been applied.

Since a six-foot St. Francis won’t fit into a carry-on, visit the tiny studio of Maurizio Cianfano (Via C. Russi 10, Lecce, 011-39/333-799-3906) who specializes in foot-high figurines of 19th-century peasants. Constantly grinning under his close-cropped hair, Maurizio wears surgical gloves and a white lab coat spattered with the gray of papier-mâché. All around him are pots of paint, bowls brimming with clay heads, and regiments of unfinished straw bodies wrapped with thread. Onto these, Maurizio crafts papier-mâché clothing, paints in the details, and attaches the peasant’s burden: a bundle of sticks across the back, a pile of wood under the arm, and a jug of wine for the free hand. Smaller figures start at about $25.

Lecce has its share of artists in the kitchen as well. Concettina Cantoro presides over a trattoria so unassuming that it’s named Casareccia (Italian for “home cookin’”). It’s clearly a converted family dining room, but along the walls are magazine clippings of Concettina demonstrating Lecce cooking to chefs in Boston and New York. She’s a bit of a surrogate mamma to the workers who lunch here and groups who come for celebratory dinners. She hates impersonal menus and instead offers suggestions: “Would you like a potato, mussel, and zucchini salad? How about meatballs for afterward, with pureed fava beans and wild chicory on the side?” By the time she’s back in the kitchen, you realize that she’s dictated your meal. Ah, well. Mamma knows best—unless she’s suggesting an after-dinner shot of the digestivo d’alloro. It’s a bitter, nuclear-green liqueur made from laurel leaves. (Trattoria Casareccia: Via Col. Costadura 19, Lecce, 011-39/0832-245-178.)

Beyond food and crafts, Lecce is celebrated for its architectural quirks. In particular, the city has its own version of baroque, which meshes the curves and curlicues of that period with the iconography and mythological beasts associated with the Middle Ages, several centuries prior. The facade of Lecce’s Santa Croce is a perfect example of the style: The building itself is curvy and baroque, but decorated with a mix of pagan references and Christian symbols, including dragons, cherubs, winged Harpies, and pot-bellied mermaids. Atop one column is an ancient symbol of Christ’s Passion: a mother pelican pecking at her breast, the blood flowing down to feed her fledglings.

For more oddball medieval symbolism, follow the coastal road south for 30 miles to Òtranto, an ancient city of twisting flagstone streets girded by a mighty wall. The mosaic floor of Òtranto’s cathedral is a phantasmagoria of fantastical creatures: elephants, peacocks, cats with human feet, bow-brandishing centaurs, and a horse’s body with three human heads.

Near the cathedral is Ristorante Da Sergio (Corso Garibaldi 9, Uranto, 011-39/0836-801-408,) a good place to digest the wild assortment of images, as well as heaping plates of linguine with shrimp. Sergio, like Concettina, prefers reciting the day’s best to you. He proudly presents an oversize plate piled with the day’s catch. If you order the roasted sea bass, he’ll insist it needs a couple of giant prawns “to keep the fish company on the plate.” As with Concettina, it’s best to go with whatever Sergio suggests. You’re guaranteed yet another happy ending.

Where to stay in Lecce? Centro Storico B&B: Via A. Vignes 2b, Lecce, 011-39/338-588-1265 or 011-39/0832-242-828, bedandbreakfast.lecce.it, $63–$85