On our first full day in India, at the New Delhi train station, a tout tried to sucker my husband, Nick, and me into buying counterfeit tickets. Near the Red Fort of Old Delhi, some guy grabbed at the crotch of my intentionally modest salwar kameez. On the way back to our hotel, the rickshaw driver got lost, ultimately failing to find the place and demanding extra payment anyway.

I was no novice wanderluster. I’d been all over the planet, and India was the halfway mark of our yearlong round-the-world trip. From then on, I decided, anyone who messed with me was going to feel the full force of my seasoned traveler’s fury. So the next morning, while Nick went shopping for books, I stayed inside, too scared and exposed to go outside by myself. Instead, to prove my mettle, I got into a fight with the officious hotel receptionist.

I hadn’t come to India on any kind of Mission Enlightenment, but the funny thing about change is how it creeps up on you when you’re busy acting like a brat. As soon as we left Delhi, the little kindnesses started: When I fell sick in the Lawrence of Arabia–worthy desert town of Jaisalmer, a restaurant owner named Rama became my temporary mother, easing my stomach pain with “desert cures” and my loneliness with long, intimate talks. In the whitewashed lakeside city of Udaipur, Nick and I met a pair of teenage art dealers, who, after selling us miniature paintings, discovered my love of Bollywood films and offered to take me to several, where they explained what was going on when the plots got too convoluted. I also mentioned my Bollywood obsession to the functionary who ran the 17th-century castle-cum-hotel in the village of Orchha; the next morning, a famous actor who lived nearby was waiting in the lobby for me. Such acts occurred almost daily, and their generosity took my breath away.

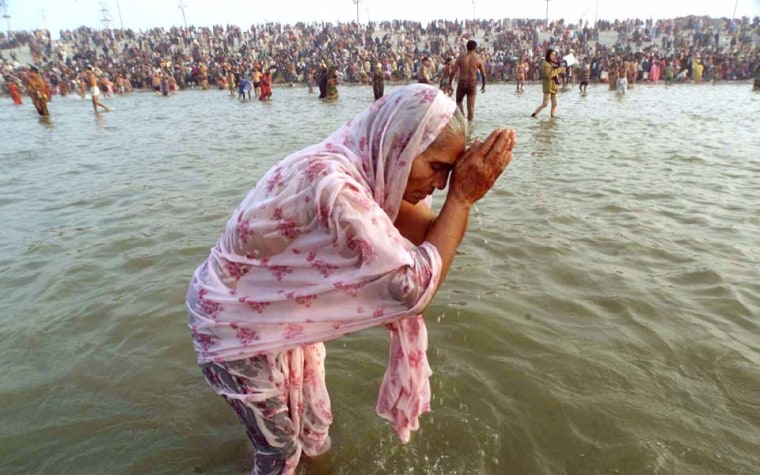

As people opened up to me, my fears of India’s chaos and otherness fell away, as did my ridiculous you-wanna-piece-of-me mentality. I became downright promiscuous in my social interactions. I followed the little boys who spoke no English as they dragged us to a swimming hole. I walked with the prostitute who lived in a tiny shared room in the slums of Bombay (Mumbai). I discussed the merits of V. S. Naipaul and Rohinton Mistry with the booksellers along Bombay’s Veer Nariman Road. I asked Jaipur’s scammy rickshaw drivers their life stories. I accepted invitations to tea with the cousin of the tailor I met in Delhi. Some people were obvious creeps, and easily avoidable, and others wanted something in return. But more often than not, the graciousness carried no ulterior motive. The more I made myself available to what was around me, the more wonderfully weird opportunities presented themselves—to act in a Bollywood movie, to go on a Jain pilgrimage, to attend a private puja prayer ceremony.

When I arrived back in Delhi nearly two months later, I was dropped off near my hotel by the father of a girl I met on the train—daily kindness number 67—and as I hurried to meet Nick, who had gone to Varanasi while I went to Bombay, I marveled at how at home I felt. It was as clear as a pair of before and after snapshots, and I wondered if India hadn’t perhaps changed me in some way, at least the way I travel. As Nick and I worked our way through Central Asia, Africa, and Europe, I saw just how deep those changes ran. The aspects of travel that once irritated me (endless queues, overcrowded minibuses) hardly fazed me, and the aspects that once intimidated me (touts, beggars, aggressively curious locals) became social events. I made friends everywhere, having unlikely adventures with African rap stars and Uzbek bakers. I wasn’t sure how or why, but India had been a turning point in the trip.

Now that I’m back in the U.S., I see that India was also a turning point in my life. I’ve started engaging the random people I meet every day: the Yemeni counter guy at the deli, the old lady buying watermelon at the greengrocer, the grumpy fellow at the community garden across the street. I’m embarrassed by how giddily grateful these small interactions make me, but for some reason they fill me with a sense of life’s wonder and of people’s generosity. They also remind me that you needn’t be abroad to find adventure. You just need to be open.

Continued: