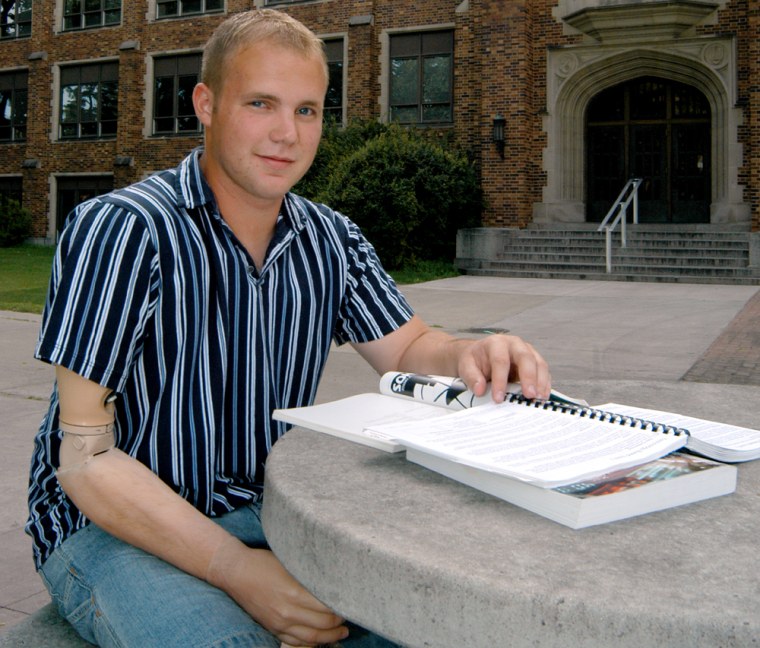

Brandon Erickson returned to the University of North Dakota this summer a changed man. Erickson, a 23-year-old National Guardsman, is back in school and struggling through rehabilitation after losing his right arm in an attack in Iraq that killed a fellow soldier.

The changes aren’t merely physical. He’s frustrated by some students’ comments about the war, less stressed by tests and deadlines. Most of all, he’s driven to finish school and make up the year he missed.

“I’m a little more focused now,” he said. “I really want to get an education. I really want to make a difference.”

As students across the United States flock to campuses this fall, educators are preparing for thousands more students like Erickson: young men and women who traded in backpacks and baseball caps for combat boots, desert camouflage and a tour of duty.

Keeping it simple

In North Dakota, officials say, college students probably make up about 60 percent of the state’s 3,200 or so Guard soldiers. When hundreds of them were sent to Iraq last year, some kept up with their studies through correspondence courses. A handful elected to take summer classes after they returned home last spring.

But officials expect most returning Guard soldiers to come back to campus this fall. Educators are trying to make the transition easier and realize that part of their job is to keep things simple.

“No one wants to make that kind of a sacrifice and come back here and be badgered by bureaucracies. They’ve had a year of it,” said Bob Boyd, the University of North Dakota’s vice president of student and outreach services.

The influx of student soldiers is keeping veterans officials busy on campuses across the country.

At Florida State University in Tallahassee, Cheryl Goodson has processed benefits for about 70 veterans for the fall semester. Goodson said the soldiers returning to school often are different from the students they were a year ago.

“It’s just a look on their face more than anything,” she said. “It’s just a whole different look. They grew up quite a bit.”

Professor Paul Sum, who teaches international politics at the University of North Dakota, said students who fought in Iraq tended to be more open-minded about the war.

“When they start thinking about the justification of being there, I think they see both sides with a lot of clarity,” Sum said.

Getting back in the swing

For many veterans, adjusting to the calm life of a civilian can be a challenge.

During his year in the Middle East, North Dakota National Guardsman Derek Holt, 22, often traveled in convoys, keeping his eyes open for ambushes or explosives along the road.

When he returned to North Dakota, Holt’s reflexes sometimes wouldn’t let him sleep through the blast of a locomotive’s whistle. Four months later, loud noises can still get his heart pumping.

“I catch myself doing that every once in a while,” Holt said. “You just kind of jump as a natural reaction.”

It’s a reaction Neil Sitz has seen often working with veterans at North Dakota State University.

“I sit and watch their eyes, and their heads are snapping at any noise or little movement,” he said. “They have to settle down — they still have that adrenaline going and that heightened awareness.”

At Southern Illinois University in Carbondale, Michael Sutton’s work-study job keeps him busy preparing education payments for fellow veterans.

Sutton, 26, spent seven years in the Marines before heading to school for the first time last spring. As a veteran of the war in Iraq, he knows what returning soldiers face when they sit down at a desk for the first time.

“People who’ve never been in the military and don’t know what the men and women in the armed forces go through on a daily basis — they definitely take for granted a lot of personal freedoms they have,” he said.

Footing the bill

Recruits give many reasons for joining the Guard, but money to pay for an education is a top attraction.

Guard members who attend college in North Dakota can get a 25 percent tuition discount and up to $500 in aid from the military. Those who go to schools in other states are eligible for assistance through a federal program.

Each state has its own system of education aid. One of the most generous is Illinois, where soldiers can get up to eight years of tuition paid, said Maj. Wanda Ward, the Illinois Guard’s education officer.

The Montgomery GI Bill, the 60-year-old mainstay of military education assistance, pays about $300 a month for books and living expenses to Guard soldiers attending college.

Officials who deal with veterans say they don’t expect the flow of student soldiers to slow down soon.

In Illinois, about a third of National Guard soldiers are students and about 40 percent are either on active duty or have returned from a deployment, Ward said.

Erickson said he is looking forward to talking with buddies from Iraq when fall semester starts. He knows they’ll be able to talk about experiences most of their peers wouldn’t understand.

“It’s kind of funny — a bunch of 20-year-olds sitting around telling war stories,” he said.