After a coin toss to decide which decorated Vietnam War veteran would speak first, talk show host Dick Cavett invited his guests to debate the issue that had divided America. The tall, long-haired veteran with the big jaw denounced the war as immoral. His clean-cut rival spoke of patriotism and sacrifice.

More than three decades after their 1971 debate, John F. Kerry and John E. O'Neill are back at it. This time around, however, Kerry is running for president, and O'Neill has become one of his most prominent detractors.

For the past few weeks, long-standing presidential campaign themes such as the economy, health care and even the war in Iraq have been effectively overwhelmed by angry charges and countercharges about what Kerry did, or did not do, in a conflict that more than one eligible voter in three is too young to remember.

Now, O'Neill and his supporters from the political advocacy group Swift Boat Veterans for Truth are focusing their efforts on the Massachusetts senator's antiwar activities after he returned from Vietnam. Earlier this week, they released a new television ad accusing Kerry of "betraying" his comrades and "dishonoring" his country by making false accusations that many of them had committed war crimes.

By his own account, Kerry returned from Vietnam "an angry young man" determined to restore "morality" to U.S. foreign policy; O'Neill saw Kerry's actions as an affront to his patriotism. That these two men came to such divergent views is especially striking, given that they skippered the same U.S. Navy Swift boat on the Mekong River, albeit at different times. An examination of their postwar paths illuminates a much broader cultural divide that was born out of the Vietnam trauma -- and is haunting American politics once again.

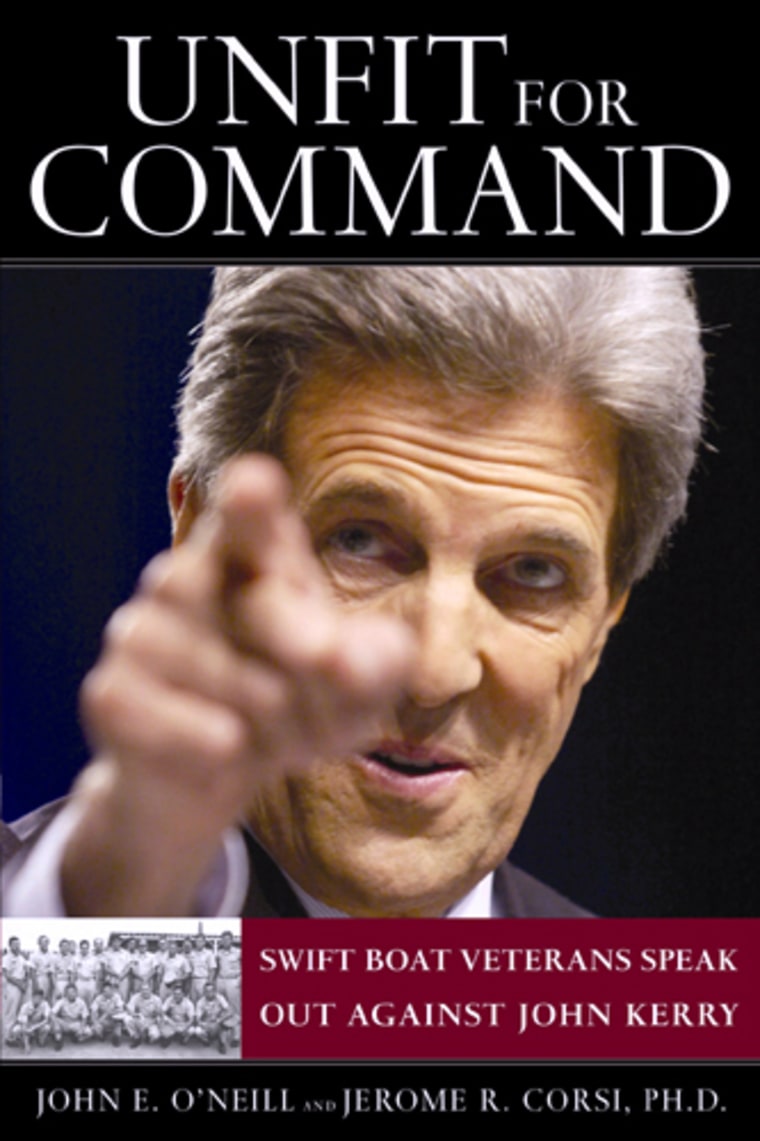

Archival records show that O'Neill, who has been making the rounds of the TV talk shows this month to promote his best-selling anti-Kerry book, "Unfit for Command," was encouraged to go on television in 1971 by President Richard M. Nixon and his aide Charles W. Colson. Nixon regarded Kerry as the antiwar movement's most effective and articulate spokesman, and the president was desperate to undercut the activist's popular appeal.

"Let's hear it from the O'Neills now," Nixon told his 25-year-old protege, after warning him that the Cavett show's producers "inevitably . . . have it stacked against you." Colson later boasted to Nixon Chief of Staff H.R. "Bob" Haldeman that O'Neill "has agreed that he will appear anytime, anywhere that we program him," according to White House records.

Swift Boat Veterans for Truth members acknowledge that their animus toward Kerry stems in large part from the speeches and statements he made after the war, particularly his allegation that U.S. forces in Vietnam routinely engaged in activities that would be considered war crimes by the Geneva Conventions. They were particularly upset by his April 1971 appearance before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in which he recounted stories by other veterans that "they had personally raped, cut off ears, cut off heads . . . [and] razed villages in [a] fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan."

"He slandered us, and now he expects us to support him or remain quiet," said Joe Ponder, a disabled Swift boat veteran who appears in the most recent anti-Kerry ad. "He discredited a whole generation of service people. He said these things happened on a day-to-day basis with the blessing of our commanders."

Veterans who are sympathetic to Kerry say that the Democratic presidential candidate is vulnerable to political attacks on his antiwar activities because of an extensive public record that his opponents are now combing for any inconsistency. Kerry has already backed away from some of his more inflammatory antiwar statements and an earlier claim that he was not present at a meeting that debated a proposal to assassinate government officials and take over the Statue of Liberty.

Many of Kerry's former colleagues in the antiwar movement continue to support him, arguing that President Bush has taken the United States into a war as devastating in its own way to U.S. prestige and moral authority around the world as Vietnam. Others bemoan what they see as Kerry's transformation from an impassioned, conviction-oriented leader into a more cautious politician who tailors his message to what works with focus groups and public opinion polls.

This reconstruction of the postwar careers of Kerry and the man who has led the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth assault on him is based on more than 20 interviews, research in the National Archives in College Park, and a review of dozens of books and newspaper articles. Kerry declined a request for an interview; O'Neill accepted.

'More believable'

The spring of 1971 marked the peak of the antiwar movement in the United States and Kerry's emergence as one of its stars. Nixon was attempting to salvage "peace with honor" in Vietnam through a policy of "Vietnamization," which involved a gradual withdrawal of U.S. troops from the country and political and military support for the anti-Communist government in Saigon. The protesters wanted Nixon to announce an immediate end to the war.

Kerry burst into the public consciousness when he was invited to address the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on April 22 by its chairman, J. William Fulbright (D-Ark.). Dressed in olive-green fatigues and combat ribbons, Kerry accused Nixon of sacrificing thousands of lives in a hopeless cause and delivered his celebrated line "How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?"

Kerry's eloquence and youthful good looks worried Nixon and his aides. As Kerry was addressing the senators beneath the glare of the television lights, tens of thousands of Vietnam veterans were camped on the Mall, in defiance of government and Supreme Court orders. The following day, Nixon expressed concern to Haldeman that Kerry had been "extremely effective."

According to a tape recording of the Oval Office conversation, Haldeman described Kerry as "a Kennedy-type guy" with "a bundle of lettuce up here," meaning medals. "He looks like a Kennedy, and he talks exactly like a Kennedy."

Nixon: "Where did he serve?"

"He was a Navy lieutenant, j.g., on a gunboat, and he used, uh, to run his gunboat up and shoot at, uh, shoot babies out of women's arms," replied Haldeman, fancifully embroidering Kerry's testimony of the previous day.

White House records show that Nixon and his advisers were so concerned about Kerry they immediately began looking around for other Vietnam veterans who would counter his popular appeal. One they came up with was O'Neill, described by Colson in a memo as "a very attractive dedicated young man -- short hair, very square, very patriotic." Haldeman told Nixon that O'Neill ("a great little sharp-looking guy") was not "as eloquent as Kerry" but was "more believable."

O'Neill, who had returned from Vietnam in June 1970, belonged to a group called Vietnam Veterans for a Just Peace, identified by Colson in a memo to Nixon as "an organization specifically set up to counter Kerry." He started making the rounds of the TV studios, delighting the White House with his fiery denunciations of Kerry and support for Nixon's Vietnamization policy.

After one such appearance, on June 6, Colson talked enthusiastically to Nixon about "this boy O'Neill," saying, "You'd just be proud of him." In conversations with Colson, Nixon referred to O'Neill as "your young man."

Colson, who now heads an organization called Prison Fellowship Ministries, declined to be interviewed, explaining through an aide that he did not want to be drawn into the current campaign. But he confirmed the accuracy of a quotation in the Dec. 2, 2002, New Yorker magazine in which he said that Nixon aides had "formed" Vietnam Veterans for a Just Peace as "a counterfoil" to Kerry and did everything they could to boost the group.

In an interview this week, O'Neill denied that Vietnam Veterans for a Just Peace was a front organization for the White House. He said the group got started "a little bit before Colson knew who we were" and received support from Democrats as well as Republicans.

"They were probably thrilled with what we were doing," said O'Neill, referring to Nixon and his aides. "But to say that they were using us implies that they were getting us to accomplish something we did not want to accomplish, which is not true. We were doing things we wanted to do."

By mid-June, according to a White House memo, O'Neill was beginning to feel "very discouraged" about his reception on TV. He had been booed by a hostile crowd on the Cavett show and wanted "to go home to Texas and get away from the eastern establishment." Colson urged Nixon to see O'Neill to boost his spirits.

Their June 16 meeting in the Oval Office was scheduled for 10 minutes, but Nixon was so engrossed in the conversation that it lasted 45 minutes. Pacing behind his desk, Nixon tried to encourage O'Neill by citing his own effort to prosecute State Department official Alger Hiss as a Soviet spy in 1948, an event that was pivotal to Nixon's political career. "Don't worry about being on the winning side," he told O'Neill. "Only worry about doing what is right."

According to a Colson memo, an awestruck O'Neill left the Oval Office saying "he had just been with the most magnificent man he had ever met in his life." ("Totally untrue," O'Neill says now.) Colson also quoted O'Neill as promising to "spend every waking moment campaigning for Richard Nixon."

White House memos show that Colson was working behind the scenes to push for a Kerry-O'Neill debate on nationwide television. "Let's destroy this young demagogue before he becomes another Ralph Nader," he wrote, referring to Kerry.

Kerry finally accepted a challenge from O'Neill to appear with him on Cavett's show on ABC on June 30. From today's perspective, their debate seems gloriously old-fashioned. Instead of boiling down their points to 15-second sound bites, the network gave the two veterans 90 minutes to talk about the burning issue of the day, interrupted only by Cavett reading ads for Calgon Bath Oil Beads ("Leaves you radiant and refreshed!").

The debate ended without a decisive victory for either side. O'Neill accused Kerry of "the big lie," arguing that he had "murdered" the reputations of 2 1/2 million service members by accusing them of war crimes. Dressed in a well-cut blue suit, Kerry told the audience he had personally participated in "search-and-destroy missions in which the houses of noncombatants were burned to the ground" and asked O'Neill if he had ever "burned a village."

"No, I never burned a village," replied O'Neill, who was wearing his only suit, a blue-and-white seersucker, with matching white socks.

After a cameo role at the 1972 Republican National Convention, when he was one of several Democrats nominating Nixon for president, O'Neill dropped out of politics, attending law school and then clerking for then-Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist at the Supreme Court. He later became a successful lawyer in Houston. It was not until the his old adversary locked up the Democratic nomination for president that he reentered the public stage.

'Top-downers'

Within Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW), as the leading antiwar veterans organization was known, Kerry was regarded as moderate and politically ambitious. Other, less well-connected vets were uneasy about his patrician manners, "JFK"-monogrammed sweaters and Gucci shoes. The leaders of the movement appreciated his public speaking skills and appointed him their principal spokesman. Lower down, there was resentment over the amount of media attention he was getting.

According to historian Gerald Nicosia, whose "Home to War" is the authoritative account of the movement, VVAW was becoming increasingly divided by 1971. The officer class -- referred to as "top-downers" -- believed in working within the political system. The grunts, or "bottom-uppers," wanted to challenge the system, sometimes by civil disobedience or violence. Kerry was very much a "top-downer," although he worked hard to preserve the unity of the movement.

Jan Barry, the founder and former president of VVAW, has a vivid memory of Kerry's performance at the "Winter Soldier" hearings in Detroit in January 1971, when more than 100 veterans gave accounts of gruesome atrocities and war crimes they had committed. "You had a room full of veterans who had bared their souls and were angry that nobody wanted to listen to them," Barry said. "Kerry stood up in front of this angry group of people and convinced them to take their anger to Washington and to Congress."

Kerry was referring to the testimony at the Winter Soldier hearings when he told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in April 1971 that he had heard accounts of American servicemen ravaging villages and cutting off heads and ears. The current ads by Swift Boat Veterans for Truth imply that Kerry was making these accusations himself, when in fact he was relating other people's accounts.

In an interview on NBC's "Meet the Press" earlier this year, Kerry described his 1971 testimony as "honest" but "a little bit over the top." "Those were the words of an angry young man," he told moderator Tim Russert.

According to FBI records first released to Nicosia, Kerry sometimes expressed fairly radical points of view. For example, he described North Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh as "the George Washington of Vietnam." He also noted with some bitterness that out "of 234 congressmen's sons eligible for service in Vietnam, only 24 went there, and only one of them was wounded."

The FBI kept careful tabs on the protesters through a network of informers, who tracked Kerry's movements. The FBI records help to disprove a long-standing claim by Kerry that he resigned from the VVAW leadership in the summer of 1971, before the organization began to flirt with proposals for radical civil disobedience and even violence.

The FBI records show that Kerry was present for a particularly contentious meeting in Kansas City, Mo., in November 1971, at which plans were discussed for the assassination or kidnapping of government officials or the takeover of the Statue of Liberty. The proposal was overwhelmingly voted down, and the files record that Kerry wanted VVAW "to stay strictly non-violent." According to the FBI files, he resigned from the organization in Kansas City after an angry showdown with radicals led by a firebrand named Al Hubbard.

Told about the FBI records earlier this year, Kerry said through a spokesman that he now accepted he must have been in Kansas City for the November meeting while continuing to insist that he had "no personal recollection" of the contentious debate. Many people associated with VVAW find this difficult to believe.

"There was no way he would have forgotten about being in Kansas City," said Nicosia, who is generally sympathetic to Kerry.

Former VVAW Kansas state coordinator John Musgrave, who served with the Marines in Vietnam, expressed extreme doubt about Kerry's stated recollection. "He had a tremendous confrontation with Hubbard at that meeting. How can he claim not to have any memory of it?"

"These meetings were chaotic, confused and very noisy," countered John Hurley, director of the Veterans for Kerry movement, which claims a membership of 300,000. According to Hurley, it was easy to confuse one meeting with another as Kerry was "flying all over the country from one college campus to another."

More than three decades later, the anti-Vietnam War movement remains split between "top-downers" and "bottom-uppers." Many VVAW members interpret Kerry's answers to Russert as a signal that he has moved away from his youthful ideals. But they are divided over whether this is a tactical concession or a deeper political betrayal.

"He doesn't have the same courage of his convictions he had back then," said Musgrave, referring to Kerry's appearance before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. "When he gave that speech, he spoke for all of us. He should either stand up for it, or explain why he no longer agrees with it. He is doing neither, as far as I can see."

"The John Kerry of 2004 is not the same as the John Kerry of 1971," said David Cline, a southern VVAW organizer. "I think he was more truthful in 1971. Having said that, I know who I want to be president. The sad reality of American politics is that any candidate has to go for the center."

Researcher Lucy Shackelford contributed to this report.