André Lugo stood among the white marble headstones and watched the soldiers salute as they lined up next to his father's coffin at Arlington National Cemetery. He listened to the guns firing 21 times in solemn tribute.

But when he looked back on the funeral a month later, it still seemed as if something was missing.

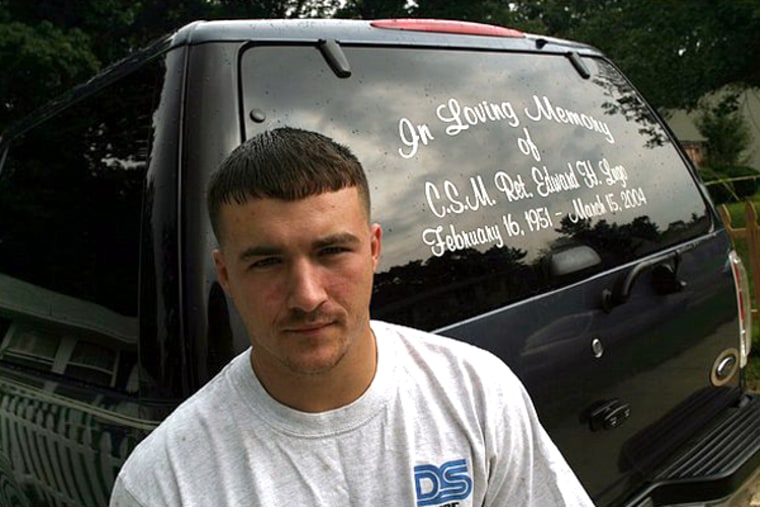

So one day Lugo, 21, came home and told his mother he wanted to show her something. On the back of his souped-up Ford Expedition, nearly the entire rear window was covered with a decal with silver script: "In Loving Memory of C.S.M. Ret. Edward H. Lugo, February 16, 1951-March 15, 2004."

His mother started to cry, André Lugo said.

Men and women of his parents' generation were raised to grieve in private and according to tradition: a funeral, a burial, a tombstone. These days, mourning is more personalized and, for many families, more public -- to the point that, in a trend some trace to stock-car racetracks, people are fighting the anonymity of death with a decal stuck on a car window.

Memorial stickers have become a familiar sight, particularly on rural roads, a flash of mortality glimpsed at 30 mph. "It's like a rolling tombstone," said Lin O'Neill, owner of a decal store in the small Virginia town of Chester.

Some decals say "Rest in Peace" or feature just a name and the dates of birth and death. Some hint at the person who was lost, with an image of a hockey stick, a motorcycle or a cross. "It keeps reminding everyone about my dad," said Lugo, whose father, a retired Army veteran, died in the spring.

The popularity of the stickers has grown by word of mouth: One person orders one, then a friend wants one, then a volunteer fire department and a family honoring a soldier killed in Iraq. They usually mark a sudden death, giving the drivers some comfort while reminding others of the loss -- raising awareness or, sometimes, just raising eyebrows.

"Why do people wear wide ties and [then] narrow ties? It's a fad," said Wayne Mast, the owner of a sign shop in St. Mary's County who often makes memorial decals for no charge.

The evolution of mourning

It took a strange cultural mix to get to this stage in the evolution of mourning. In recent decades, counselors led by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kuebler-Ross, who died Tuesday, helped bring death out into the open. The message changed from "Don't dwell on grief" to "It's okay to keep looking back." Now there are funeral videos, roadside memorials, personalized caskets.

Gary Laderman, an Emory University professor who wrote a book about funeral traditions, said, "We are in the midst of a cultural revolution around death."

Some say the decals started with NASCAR culture. Race cars have had numbers and sponsor decals for years. When two drivers died in the early 1990s, fans made black circles with the car numbers for their back windows. People put lettering on their race cars, "In memory of . . . "

Changing technology made it easy -- and cheap -- to customize graphics. When racing legend Dale Earnhardt was killed in a crash in 2001, fans bought all sorts of decals; his car number with a halo and wings, or a checkered flag at half-staff.

O'Neill, who lives in Chester and races cars there, made a decal for his modified Chevrolet Monte Carlo after a crew member died several years ago. "There's a void there," O'Neill said. "We didn't want to forget him."

In many ways, memorials on cars make perfect sense, said Ken Doka, a senior consultant to the Hospice Foundation of America. Drivers can say whatever they like on their bumpers or windshields and spread that message to thousands. Most people spend an awful lot of time in their cars, especially those who commute, as André Lugo does from Waldorf to the District.

"In a mobile society, it's a way to mark that you're mourning," Doka said. And with cremations an increasingly common alternative to burial, many mourners don't have a gravesite to visit.

Beyond the funeral

After the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when the whole country was mourning, people stuck flags and "We will not forget" stickers on cars. Then came the war in Iraq, and families and supporters of U.S. troops ordered decals. John Thomas, who sells stickers through a Web site, said he sometimes includes a note with a decal. "I'll write in there, 'Our hearts go out to you -- thank you for your service.' "

About 40,000 people die in car accidents every year in the United States. And along the sides of the roads, mourners place flowers, signs and tributes to people who died there.

A carved wooden cross stands next to a white cross on a highway near Lexington Park marked "to Karlie"; in Calvert County, a cluster of shiny balloons floats by the edge of Route 4. It is illegal to put things in the right-of-way along Maryland and Virginia roads, but people do all the time. Virginia transportation officials ask families to contact them for guidance in creating a memorial that will not be hazardous to drivers.

Before dawn one morning last October, Debbie Hardy's daughter went with a friend's family to bring apples to the farmers' market. A drunk driver shot around a curve near their home in Harford County, Md., and smashed into the truck. Janet Hardy died instantly, days before her 14th birthday.

It was so sudden, so senseless and so devastating that Debbie Hardy, a single mother who works as a community health nurse, struggled to find a memento to last beyond the funeral. She had seen memorial decals on cars, so she searched the Internet and ordered one that said, "Janet Marie Hardy, our soccer angel."

She used the same font Janet chose for instant messaging. Then she added another decal to her Chevy Cavalier: "Slow down. My daughter was killed by a drunk driver."

André Lugo, who works as a steamfitter, used to fix cars, catch bass and hunt deer with his dad. His father -- really his stepfather, who married his mother when André was a toddler -- went to the hospital unexpectedly this spring.

"It was pretty messed up," André Lugo said. "I couldn't believe it. He was healthy, and then all of a sudden. . ."

Lugo bought the SUV just a day or two before his father got sick; they had planned to fix it up and take it to car shows together.

When he got the car decal made and they stuck it to his rear window, it felt good, he said. People who knew his father through the Army Corps of Engineers stop him sometimes to talk. At car shows, people ask him about the decal. When he's stuck in traffic on his commute, he can see people in his rearview mirror -- their lips moving, reading about his dad, wondering.

"It's a good memory," he said. It's always there, right on the window, every time he looks back.