Biotechnology is meeting art in Venezuela as scientists try to save the country's art treasures from being ruined by its tropical insects, fungi and humidity.

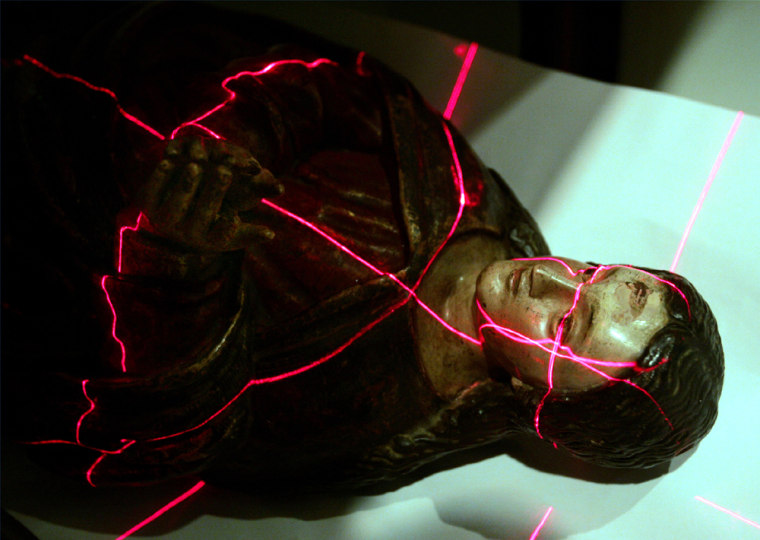

An 18th-century colonial wood carving of the Virgin Mary is the guinea pig for a novel alliance of biologists, DNA experts and art curators who are working to preserve Venezuela's rich cultural heritage from the ravages of the tropical climate.

The team is racing to save a 2½-foot statue known as the "Immaculate Creole Virgin" from destruction by wood-boring beetles.

They plan to "vaccinate" the carving with spores of a bacterial toxin that is deadly to insects but harmless to humans and, they hope, to works of art as well.

"What we're doing is using biotechnology techniques that are employed in forensics and agriculture, but applying them to works of art," said Jose Luis Ramirez, a Venezuelan genetics expert who runs a Latin American biotechnology program for the United Nations University.

Major infestation

When Tahia Rivero, curator of the private Banco Mercantil collection that owns the Creole Virgin, saw the statue's red, green and gold robes pockmarked with beetle holes, she knew she had a major infestation problem. "They are eating it up inside," she said.

If the problem were not tackled, the voracious beetles could eventually reduce the carving to sawdust, the fate of many historic wood statues in the insect-infested tropics.

Rivero also knew that if she applied traditional liquid or gas chemical pesticides, she risked damaging the delicate paint pigments of the statue and expanding or splitting the wood.

So she consulted an art conservation expert, Alvaro Gonzalez, who got in touch with Ramirez and colleagues at Venezuela's Institute of Advanced Studies, or IDEA, to see if they could come up with a solution to save the carving.

Tomography and toxins

They decided to give the Creole Virgin high-tech treatment. "We're bringing together the two worlds of art conservation and biotechnological science," said Gonzalez.

First, the statue was taken to a local clinic to undergo a tomography scan, also known as a CT scan, a computerized X-ray technique that joins together multiple images.

The probe clearly revealed the burrowing holes of the beetles and showed that the statue was constructed from three different kinds of tropical wood, one of them mahogany.

Samples taken from the wood allowed an entomologist to identify the culprit as Calymmaderus punctulatus, a tiny beetle that attacks furniture, wooden posts and carvings in the tropics.

Using techniques now commonly employed by forensic scientists to identify murderers or rapists, the team then ran the samples through a genetic analyzer to find the precise DNA "molecular fingerprint" of the invading insect.

This allowed them to identify a perfectly matching biological antidote in the form of a bacterial toxin known as Bacillus thuringiensis, or Bt, which is used as a natural insecticide to eradicate crop pests.

The Bt toxin, which occurs naturally in soil, kills worms, beetles, caterpillars and moths without harming humans and animals. "The bugs go belly-up and die," Ramirez said.

‘Vaccinating’ an art treasure

A Mexican colleague is developing the specific crystal formula of the Bt toxin that will be inserted into the beetle's burrows in the carving, using modern surgical probes.

"We'll be sticking the spores in there and spreading them about," Ramirez said.

Once implanted, the spores remain active, preventing the recurrence of the insect pest. "It will be like being vaccinated against flu," Rivero said.

Excited by this new use of biotechnology, the team is hoping to restore other works of art from Venezuela's Spanish colonial period, such as paintings, books and manuscripts threatened by bugs and fungi that thrive in heat and humidity.

"The tropics are great for going to the beach but terrible for a nation's works of art," said Gonzalez.

Ramirez said anti-bacterial peptides occurring naturally on the skin of frogs could be used to combat fungi attacking art treasures.

"The idea is that this biotechnology application could be used massively in the work of art conservation," Rivero said.

The team is also working to set up a DNA databank of the original materials used by colonial artists and artisans and of the biological pests that can attack them.

If the operation on the Creole Virgin proves successful, one of the next projects the group has in mind is to restore Venezuela's "Liberator's Archive," a collection of letters belonging to Latin America's 19th-entury independence hero Simon Bolivar that is under attack from insects and fungi.