Maher Hamra pointed to a stack of papers piled high on his desk with the commanding air of being in charge. More than 10,000 leaflets were distributed with the message that participation in Iraq's Jan. 30 elections is "a religious and national duty." The Shiite Muslim sheik also boasted that his office hung 150 banners fluttering along streets with the same message.

Over the past month, Hamra said, that message was uttered daily by turbaned prayer leaders in the 50 mosques in his neighborhood of Kadhimiya, built around Baghdad's most prominent Shiite shrine. Delegates were dispatched to more than 20 high schools. And the elections were the subject of seminars and lectures organized every few days by Hamra's office, which wields religious authority in the name of Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani, the country's preeminent religious figure.

"We're deciding our destiny," said Hamra, 48, a burly, bearded man with an ever-present cigarette next to a scalding glass of sweetened tea. "We have a responsibility to help build the new Iraq."

Electioneering from the mosque

As Iraq's first nationwide elections in more than a generation near, Hamra and other Shiite clergy, perhaps the country's most powerful institution, have led an unprecedented mobilization of the Shiite majority population through a vast array of mosques, community centers, foundations and networks of hundreds of prayer leaders, students and allied laypeople. The campaign has become so pitched that many Iraqis may have a better idea of Sistani's view of the election than what the election itself will decide.

The momentum they have created has made a delay in the ballot difficult, if not impossible. Voters will choose a 275-member National Assembly, but powerful groups within Iraq's Sunni Muslim minority are boycotting the election or have called for a postponement so that they can bring calm to restive Sunni regions where insurgents have threatened to attack those taking part.

At the same time, the clergy's campaign has virtually ensured support among Iraq's Shiites for an alliance of about 240 candidates that was brokered this week and has the backing of Sistani. Along with at least token representation of Iraq's ethnic and religious minorities, the slate brings together powerful, mainstream Shiite religious parties allied with the interim government, and also a popular junior cleric, Moqtada Sadr, who until two months ago was leading an armed rebellion against U.S. troops.

"Who wants to boycott, let them boycott, but the elections will happen regardless," said Hamra, sitting in an office with white walls bare but for a portrait of Sistani reading the Koran.

A show of power

In its fervor and force, the Shiite campaign reflects some of the most powerful forces shaping a country that has gone in two years from tyranny to invasion to a muddled aftermath perched between war and peace.

The campaign has charted the direction of Iraq's fledgling civil society, at least in Shiite areas, where the clergy, almost unrivaled in their sway and authority, have put a religious stamp on public life. More troublesome, though, the pre-election season has laid bare the sectarian fault lines that have begun to emerge, pitting Hamra and other religious Shiites who are eager for power commensurate with their numbers against Sunnis suspicious of both U.S. intentions and Shiite ambitions.

"We should not be deceived by people who are trying to keep us away from casting our votes in the ballot boxes, giving the excuses that the polling stations will be bombed," said Laith Haideri, the Shiite prayer leader at Baghdad's revered Buratha Mosque. "It is a duty for everyone to silence these schemes that are calling on people not to attend and participate in these elections."

Haideri is a foot soldier in the clerical campaign. During Friday prayers, he stood at a podium draped in green, holding a gold-colored sword in one hand. In his sermon to 100 worshipers, gathered on red carpets beneath ceiling fans and chandeliers, he voiced what has become a staple of the mosque's sermons in recent weeks: Voting is obligatory.

"We must encourage those fearful and hesitant," he said. "Elections are the best way to bring order, security and an accepted, legitimate government."

'One vote is like gold'

Outside the mosque, posters vied for space along the walls. One read, "The enemy of Iraq is the enemy of democracy, justice and elections." Another quoted Sistani: "One vote is like gold, but even more precious."

The January elections are more than just a vote for Iraq's long-oppressed Shiite majority. For the first time in the country's modern history, the community stands at the brink of inheriting power by peaceful means that was long monopolized by Sunni Arabs. The Sunnis make up about 20 percent of the country's population, although without an accurate census the ethnic and religious proportions are a subject of dispute.

For some Shiites, the elections will rectify perceived mistakes made at the country's founding. In 1920, the Shiite clergy led a revolt against the British occupation that followed World War I. Once it was put down, the clergy kept up their opposition, rejecting participation by Shiites in elections that followed and discouraging a Shiite role in the government and its institutions, which soon became dominated by Sunnis, particularly the urban elite that was fostered by Iraq's imperial rulers for centuries.

This time, many of the mainstream Shiite clergy are voicing a very hostile message toward the Sunni-led insurgency, calls that have sharpened amid mounting bloodshed that, last week, targeted a Shiite community center in Baghdad.

"They are not serving the interests of the people and the interests of the country," Haideri said in his sermon. He went on to call the insurgents terrorists and sarcastically referred to them as "brother mujaheddin," a sacred term for Islamic fighters.

At that, the worshipers broke into a chant, under the shadow of minarets topped with green domes.

"God is greatest!" they shouted three times. "Victory to Islam! Death to Saddam!"

Role of war

Shiite empowerment is just one facet of the clerical campaign, and it is usually couched in coded language. More common are visceral appeals to an electorate that has grown fatigued and disillusioned with the carnage of war.

Banners fluttered in the brisk breeze of Baghdad's winter on the road to the twin domes of the Kadhimiya shrine, which was bustling with pilgrims and vendors selling honeyed sweets and tapes of Shiite laments. At one end of the road, banners promised a new era of stability with the vote. At the other, they cast the election as the surest way to end an occupation that has grown increasingly unpopular.

"Brother Iraqis, the future of Iraq is in your hands. Elections are the ideal way to expel the occupier from Iraq," one white banner proclaimed. "Brother Iraqi, your vote in the elections is better than a bullet in battle," an adjacent sign read.

Along an iron fence that borders the shrine were appeals cast in nationalist and religious terms.

"Not voting is a reward for terrorism," one read. "If you don't consider it a religious duty, then your national duty calls on you to vote," another intoned. More bluntly, one read: "Voting honors the blood of martyrs."

At times, the slogans insist on blind loyalty to Sistani. "Everyone is with you," a banner in the sacred city of Najaf proclaimed.

"The clergy are advocating elections 100 percent," said Sami Shamousi, the prayer leader of a Shiite community center in downtown Baghdad. "It has become a religious responsibility for us to encourage participation in the elections."

Voter education

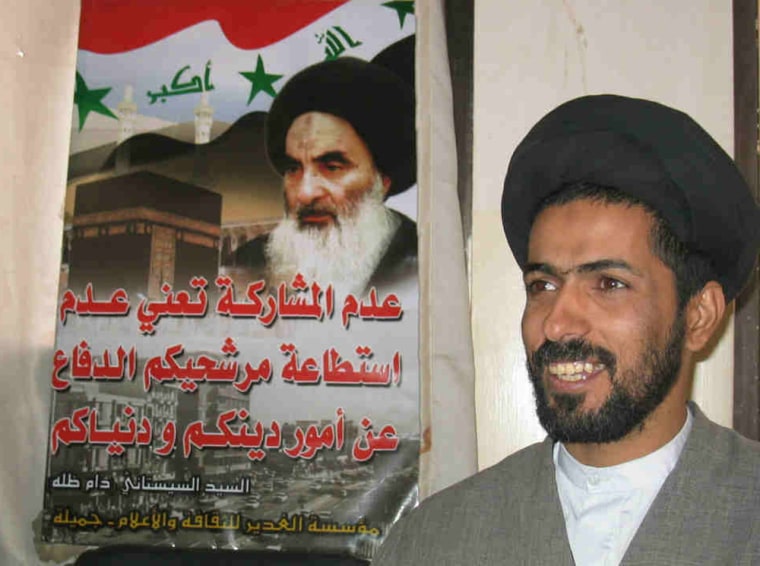

At his worship hall, he has distributed about 200 leaflets printed by the Ghadir Foundation, a community organization based in the sprawling slum of Sadr City that is loosely supervised by Sistani and other senior ayatollahs. Stacks of posters with Sistani's portrait were piled in dimly lit rooms, darkened by an electrical outage. On shelves were bundles of leaflets and pamphlets that present questions and answers about the vote: "What are we electing?" and "What does proportional representation mean?"

In a second-floor office sat Sayyid Hashem Awadi, 38, a gaunt cleric in black turban and gray gown who directs the foundation's staff of 30. For 65 days, he said he had been too busy to return to his home in Najaf.

"This stage is too critical," he said. "We're afraid of failure."

On his desk was an Arabic-language pamphlet on civil society, a phrase that usually describes a vibrant give and take between citizens and their government. The pamphlet, printed by his foundation and emblazoned with a map of Iraq, notes the term was imported from the West. But it adds, "In reality, the crises sweeping our societies force us to seek help though other people's experiences."

Awadi, whose speech shifts effortlessly from Western thought to Islamic principle, nodded his head in agreement.

Iraq, he said, was long a militarized society, where in Hussein's days "you either obeyed orders or you are killed." Awadi's vision was a society in which opinions were respected and disputes were "not a reason for killing each other." The way to create that society was through the elections in January, he said, a process in which people's opinions would be respected.

"It's a matter of the people's choice," he said. "What do the people want?"

"Our job and our task is to explain these things," the young cleric went on, raising his voice over the cascading sound of horns that poured through his window from traffic jams outside. "There are many questions in the minds of the people."