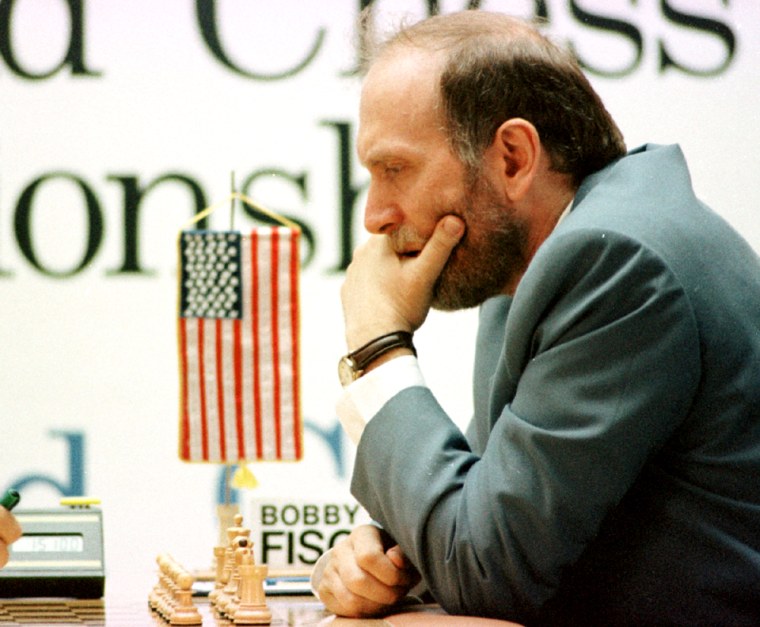

It may be hard for some to understand why Iceland would offer a residency permit to Bobby Fischer, the surly former chess champion now detained in Japan and wanted in the United States.

But Fischer put this small, isolated country on the map during his career, and some Icelanders say it’s time to repay the favor.

“When Fischer came here in 1972 to play chess with Soviet Boris Spassky, it was the biggest international event to take place in Iceland in the then 28-year history of the republic,” said Hrafn Jokulsson, chairman of the chess club Hrokurinn, or the rook.

'We don't forget our friends'

The next year, President Richard Nixon and French President Georges Pompidou visited Iceland, and the 1986 meeting between President Ronald Reagan and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev would not have taken place without Fischer, Jokulsson said.

“He put Iceland on the map, and we don’t forget our friends,” said Jokulsson, who has campaigned on Fischer’s behalf.

Fischer — believed by many to be the best chess player ever — has been sitting in Japanese immigration detention since July, after he was caught trying to board a flight for the Philippines with an invalid passport.

He is fighting a deportation order to the United States, where he is wanted on charges of violating international sanctions against Yugoslavia for playing chess matches there, a 1992 rematch against Spassky, which Fischer also won.

On Wednesday, Iceland approved a residency permit for Fischer, a move that could anger both Japan and America. On Friday, Fischer’s supporter John Bosnitch told reporters in Tokyo that the chess master wants to go to the northern nation.

“Bobby Fischer accepted to go to Iceland,” Bosnitch said.

A 'special connection' cited

The offer from Iceland came after Fischer asked his Icelandic friend, retired police officer Saemundur Palsson, about living there. The Icelandic Chess Association lobbied hard in favor of Fischer being granted asylum, and that led to the government’s offer.

Illugi Gunnarsson, an assistant in the Foreign Ministry, told The Associated Press that the decision was “due to the special connection Bobby Fischer has to Iceland as being part of one of the major events of Icelandic history.”

He noted that “there are a lot of chess enthusiasts in Iceland.”

The U.S. ambassador to Iceland, James Gadsden, was notified of the decision at a meeting with Foreign Minister David Oddsson on Wednesday.

On Thursday, the Icelandic ambassador to Tokyo notified the Japanese government.

The American ambassador said that since Fischer broke U.S. law the case is now in the hands of the Justice Department.

Fischer, 61, has denounced the U.S. deportation order as politically motivated. He wants to renounce his U.S. citizenship and has applied while in detention in Tokyo to marry a Japanese chess official. His supporters have repeatedly called for his release.

Hurdles remain

Fischer’s plan to leave Japan faces hurdles because he lacks a valid passport, though Bosnitch on Friday said Iceland has agreed to let him enter without one. Japanese officials have said he could go to a third country only if the United States refuses to take him.

Gunnarsson said he did not expect his government’s decision about Fischer to affect U.S.-Iceland relations.

“The government makes its decisions in accordance with the country’s best interests, as always. It has a close friendship with the United States, and this is not expected to change,” he said.

When asked whether the move could affect the government’s overall immigration policy, he said Fischer’s case was “special.”

Iceland and the United States have an extradition treaty, and Gunnarsson said Iceland would deal with a U.S. extradition request “when the time comes.”

“The first step is to see what the response will be from the U.S. and Japan, as well as from Fischer himself,” he said.

Fischer has not visited Iceland since his 1972 chess match, but he has remained in frequent contact with Palsson.

He has baffled many with his erratic and reclusive behavior.

He virtually disappeared from the limelight for years before the 1992 rematch. In recent years, he has emerged from silence in radio broadcasts and on his Web page to express anti-Semitic views and rail against the United States.