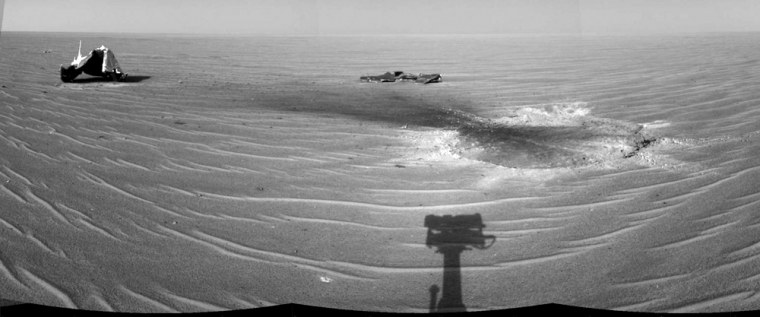

One of the Mars rovers that have spent most of the past year studying the ruddy rocks and soil on the Red Planet is now taking a close look at some of the junk it shed during its fiery descent last January.

Over the next few weeks, Opportunity will examine the heat shield that it jettisoned on Jan. 24.

“The reason for looking at these things is to design for future missions and make them safer,” Ethiraj Venkatapathy, technology manager for planetary exploration at NASA's Ames Research Center, said Wednesday. “With the heat shield, you have one chance. If it fails, the whole mission comes to an end.”

It is the first time scientists will have an opportunity to do a close-up inspection of a shield after it has landed on another planet.

Opportunity and its twin, Spirit, landed on Mars early in 2004 and have since found clear evidence that the planet was drenched with water at some time in its history.

Opportunity’s heat shield, a cone 8 feet (2.4 meters) in diameter, withstood temperatures up to 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit (1,480 degrees Celsius) and speeds up to 12,000 mph (19,200 kilometers per hour) before it was jettisoned as planned. It was going about 300 mph (480 kilometers per hour) when it hit the surface, and now lies in pieces in the dust.

Giant air bags cushioned Opportunity’s landing.

Scientists are especially interested in getting a close look at what used to be the outer skin of the shield, made of a lightweight material six-tenths of an inch (1.5 centimeters) thick.

Venkatapathy said if the blackened skin was not charred all the way through, future missions might be able to save money — and reduce weight — by using a thinner layer.

He said the U.S. space program has never lost an interplanetary probe because of a heat-shield failure.

“We want to keep it that way,” he said.