Perhaps there’s no better image of lesbian visibility than the cast of “The L Word” introducing pop star Reneé Rapp in front of two giant pairs of scissors last week on the Coachella stage.

Rapp, 24, has been on a steady rise after starring in “Mean Girls: The Musical” and hitting the Billboard charts with her Megan Thee Stallion collaboration, “It’s Not My Fault” (choice lyrics include “Kiss a blonde/kiss a friend/can a gay girl get an amen?”). For her Coachella debut on April 14, Rapp didn’t skimp on the Sapphism: She brought her guitarist girlfriend, Towa Bird, on stage for a duet and a kiss, and she had her self-proclaimed idol, bisexual sensation Kesha, join her for a feminist update of Kesha’s hit song “TikTok.”

In addition to Rapp, the music festival — which brings hundreds of thousands of fans to Southern California every year — featured queer artists Chappell Roan, Brazilian artist Ludmilla, Brittany Howard, Victoria Monét and Billie Eilish, the latter two fresh off Grammy wins.

Like Coachella, the Grammy Awards in February were another blockbuster music event where women — and queer women in particular — reigned supreme: Bisexual musician Phoebe Bridgers of boygenius was the night’s biggest winner; pansexual Miley Cyrus earned both best pop solo performance and record of the year; and, of the performances, none was hailed more than singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman’s return to the stage for the first time in two decades.

Having lesbians and other openly queer women center stage at major music events, however, has certainly not been the historical norm. For more than half a century, the impact LGBTQ women have had on the modern music industry has gone largely unsung. That, however, is starting to change, with artists no longer having to be coy about their personal identities or keep them separate from their public persona to be offered opportunities in the industry.

“I think we’re only now becoming more aware of that, or being able to publicly discuss it,” said music historian and author Evelyn McDonnell. The closet, she said, has been a hindrance to the championing of and acknowledgment that queer women have been long deserving in shaping rock and popular music of all genres, from hip-hop to country.

A brief herstory of 20th-century music

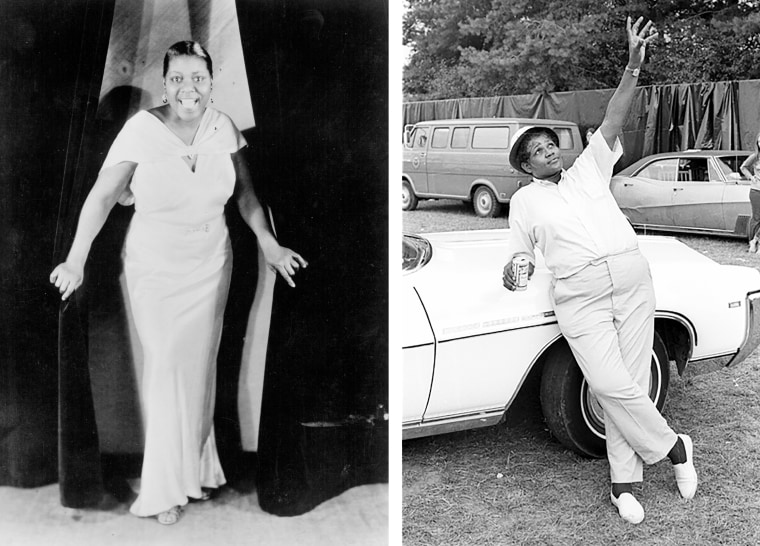

Though they rarely get the credit, queer Black women were hugely influential in planting the seeds in the early 20th century that grew into rock ‘n’ roll, rhythm and blues and pop music, whether they got their start in the church, on the block or on the Chitlin’ Circuit.

“If you go back and look at Bessie Smith, Big Mama Thornton — they were not publicly identifying themselves as queer, necessarily, but clearly signaling in their lyrics and dressing in suits,” McDonnell said. Thornton, who helped bridge the gap between blues and rock and roll, was just this week entered into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

By the late ’60s, rock ‘n’ roll had major crossover appeal and coexisted with the women’s, Black and gay liberation movements. Bisexual rock icon Janis Joplin was quick to pay tribute to foremothers like Smith and Thornton, but she and singer-songwriters Janis Ian and Joan Baez were not publicly identified as anything other than straight until much later in their careers.

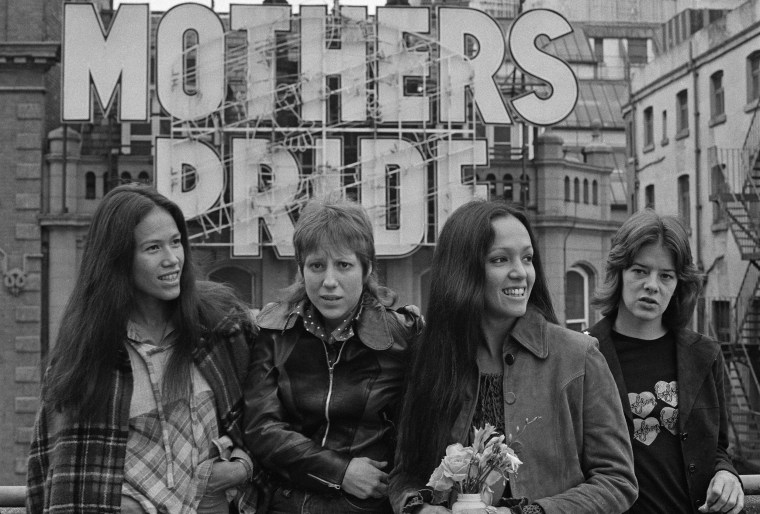

Despite the success of Joplin, Ian and Baez, music labels, festivals and television and radio programs were loath to champion women artists — much less openly queer ones. Instead, they provided platforms for oft-misogynist male bands whose songs became ubiquitous. Even an exception like The Runaways’ predecessor, Fanny, the first all-women’s rock band signed to a major label, failed to attract the kind of support needed for wider success, instead relegated to being treated like a novelty act.

“Somehow the world was not ready for them,” McDonnell said of Fanny.

The problem of sexism and homophobia was bigger than music, but the sisterhood that was born out of the feminist consciousness-raising of the ’70s ultimately fostered a network of women-run record labels, music festivals, radio programs and production companies created by women who shared skills with one another through workshops and mentorships. In 1973, Kate Millett, the lesbian author of “Sexual Politics,” held the first feminist music festival, in Sacramento, while, simultaneously, a group of queer women in Washington, D.C., started the women’s music label Olivia Records, with trans woman Sandy Stone audio engineering several of its early albums.

Calling the genre “women’s music,” an entire community was galvanized by women excited to see and hear themselves reflected on stages and stereos and in song, especially when it came to expanding on both the vastly diverse experiences of womanhood and music itself.

“They were making music that was not necessarily oriented towards a pop audience,” McDonnell said. “It was more folk; it was more world music-oriented at a time when that wasn’t necessarily what was selling. In some ways, maybe ahead of their time.”

Though not all those involved with women’s music were queer, most were, and that kind of visibility and representation was even more integral into the 1980s. It was equal parts feminism and pride that fostered an environment for female musicians and thousands of fans willing to shell out for concerts, albums and merchandise. The Indigo Girls, Melissa Etheridge and Tracy Chapman were all part of the women’s music circuit in the ’80s, building fan bases and scoring record deals with labels eager to capitalize on the proven power of the pink dollar. But with a backlash against feminism and the gay community during Ronald Reagan’s tenure in the White House, artists looking to get radio play had to dodge questions about their identities and stayed firmly planted in the closet, at least in public.

“The record labels were trying to have their cake and eat it, too,” McDonnell said. “They clearly saw the market for these audiences and that it was particular to an audience, right, but they wanted to also have them appeal to a nonqueer audience and therefore try to keep them from saying that they were queer artists.”

Simultaneously, queercore was born in the mid-’80s out of hardcore punk’s rampant racism and homophobia, and the subgenre’s growth alongside burgeoning third-wave feminism spurred the next big moment for women in music.

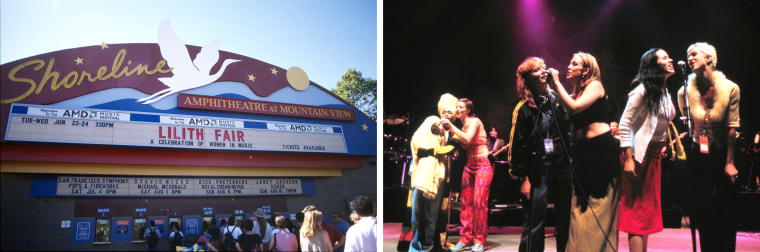

During the heyday of the “Women Who Rock” era in the ’90s, out lesbian and bisexual women involved with the riot grrrl movement and indie folk rock (such as Ani DiFranco) saw their influence usurped by the mainstreaming of “angry women” like Alanis Morrisette and Courtney Love. Lilith Fair’s launching in 1997 with corporate sponsors and Indigo Girls and Chapman playing on the mainstage alongside festival creator Sarah McLachlan was not without precedent, though it’s often incorrectly hailed as the first all-women’s music festival of its kind. Just like in women’s music, Lilith Fair had to contend with issues related to racism, responding to a call for a more diverse line-up in subsequent festivals that expanded to include not just more women of color, but women of varying genres as well.

By the time Lilith Fair was attempting a re-up in the mid-2000s, it was clear that women-centric festivals were becoming fewer and further between with a lack of financial support and a cultural insistence that they were no longer necessary.

Continuing to carve out space

While queer women — like Reneé Rapp, Billie Eilish and Janelle Monae — can now be found on some of music’s biggest stages, they are continuing to carve spaces for themselves on a smaller, yet meaningful, scale as well.

In Los Angeles, for example, concert photographer Betsy Martinez and her wife, Cynthia Temblador, have dedicated their newly opened Fan Girl Cafe to women in music with a special emphasis on queer and nonbinary musicians.

Located in the gayborhood of West Hollywood, Fan Girl is a neon pink paradise with an entire wall dedicated to live shots of queer artists like Julien Baker, Christine and the Queens, Tash Sultana and St. Vincent (as shot by Martinez and friends), and a small stage for live performances.

At shows, Martinez and Temblador said, they would see women gathering en masse as fans of queer artists and wonder where they’d come from, where they were going after the show, and how to provide a safe, music-centered space. Fan Girl Cafe was their answer.

“One person asked me one time: ‘So you just like any music because it’s a lesbian?’ And I’m like, ‘No, but if they’re good, I’m going to support them even more than probably another artist because they’re relatable,’” Martinez said. “And for the longest time, artists were in the closet, or their lyrics were changed to reflect a narrative that wasn’t true to them, so it’s important for me to make a space where people can feel comfortable being themselves and listening to music that they love.”

Fan Girl caters to a present but underserved community that is only growing in numbers with coworking weekdays, open mics and a book club. It recently hosted a night with Our Lady J and has several more events in the works.

“Our big idea for this is to eventually grow to a point where we can get these artists that we love, when they’re in town playing and do an underplay where they maybe come in do something special for their fans or like Q&As and meet and greets, because I think like we created a nice environment to do those kinds of things,” Martinez said. “So that’s our big goal, is to connect artists who have done a lot for their fans, to meet them face to face.”

Lesbian singer-songwriter Zolita, 29, has cultivated a faithful following since the video for her song “Explosion” went viral with 20 million views in 2015, when she was a student at New York University. Since then, she has released two EPs, 2018’s “Sappho” and 2020’s “Evil Angel” and has a third, “Queen of Hearts,” due out at end of May.

Zolita said she felt empowered by artists like Etheridge as well as the queer community she’s a part of and surrounded by. She said the massive response to “Explosion,” a song about falling in love with your best friend, validated her choice to be explicit about her identity as a lesbian in her music and her public persona, as well as her desire to work with as many queer collaborators and women as possible.

“If you can prove yourself and prove that there are so many fans there, it’s undeniable,” Zolita said. “You’re going to have to be given those opportunities.”

Zolita said she’s not particularly concerned with winning a Grammy and has more interest in the Video Music Awards, where Sapphic performances have come from the likes of Madonna and Britney Spears rather than any actual queer women thus far. Before now, faux lesbianism was easier to swallow than actual Sapphic leanings, but Zolita and her peers like Roan and Rapp are seeing success with being themselves — a luxury afforded by lineage.

“I feel like I’m surrounded by so many incredible female artists and have gotten a chance to write and work with a lot of them,” Zolita said. “It’s so exciting to see what a renaissance is happening in music for women.”

While queer women are continuing to establish their influence and are starting to get their due on music’s most high-profile stages, women, in general, continue to have to prove themselves and their ability to reach a wide audience. As a smaller segment of an already marginalized population, queer women can still be seen as having limited appeal, despite their popularity proving otherwise.

A dearth of women headliners at the biggest music festivals has led to the Book More Women initiative, which found that in 2024, less than 25% of musicians booked at major U.S. music festivals were women or nonbinary people. And while the National Women’s Music Festival is celebrating its 48th anniversary this June, it is now one of the few women-centric stages. when there used to be several like it all over the country.

“Those were really empowering events,” McDonnell said. “Even Lilith.”

Book More Women’s impact can be seen at the Washington, D.C., festival All Things Go, where its partnership with the festival ensured 81% of acts included at least one woman or nonbinary artist. And while Renee Rapp, Chappell Roan and Janelle Monae are among the headliners at All Things Go, they still get lower billing than at other festivals like Bonnaroo or Lollapalooza. Still, bringing their full selves to the stage is part of a palpable shift. For artists like Zolita, who will tour around her new album this fall, the closet is simply out of the question.

“My whole brand is so just unabashedly queer, and all of my stories are about women falling in love with women,” Zolita said. “That is my whole entire brand and my platform. No one’s told me to stray from that, and I’m grateful.”

For more from NBC Out, sign up for our weekly newsletter.