For seven years, Myong Sool Chang woke up at 6 a.m. on Fridays, drove an hour from Boston to New Hampshire, picked up his newspapers, then drove back to deliver them.

He dropped stacks off in restaurant entryways and corner stores across the city’s fledgling “Koreatown” – also known as Allston – before mailing copies to other New England states. The whole “mission,” as he called it, would last until 9 p.m. most weeks.

“At the end of every Friday, I almost collapsed,” Chang told NBC News. “But these days, it’s gotten a lot easier.”

“I can’t give up the paper newspaper. When all the people give up the paper newspaper, then I can finally give up.”

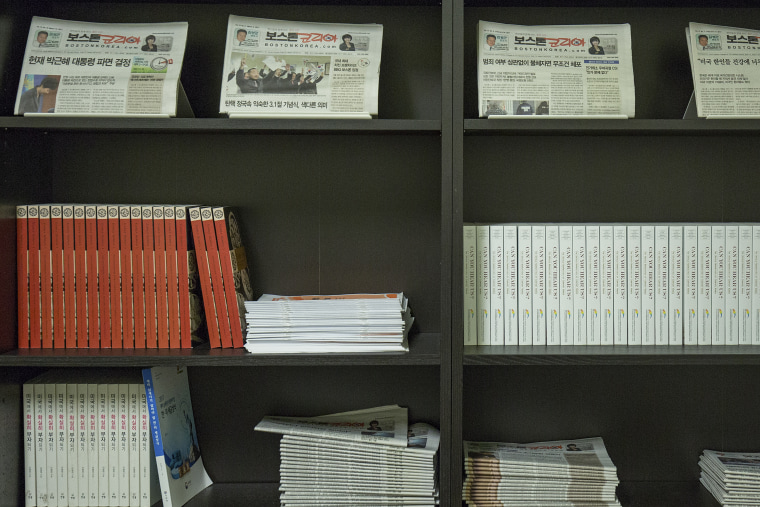

Chang is the 49-year-old founder of Boston’s last-standing Korean language newspaper, Boston Korea, which he said he has managed to grow from a profitless, pro-bono operation in 2005 to a staff of five today. But in a time when newspapers are routinely buckling under financial pressures, Chang has yet another challenge before him: the Korean population in Allston is dwindling – and fast – just five years after The Boston Globe reported it was growing “strong roots.”

Estimates from the American Community Survey suggest that while Boston’s overall Korean population is rising, Koreans living in Allston have dropped by nearly 63 percent between 2011 and 2015. Though many others live in the nearby neighborhood of Brighton and other Massachusetts towns — Newton, Lexington and Cambridge — Allston’s identity as the epicenter of Korean social life could disappear almost as quickly as it started.

“It felt like it was growing until the last three to four years. I don’t know if it’s a Koreatown anymore,” Seung-youn Woo, a 26-year-old pharmacy student and previous translator for Boston Korea, told NBC News.

Woo’s parents shut down their Allston internet cafe in 2016, and several other Korean businesses have likewise closed their doors in recent years, including a popular karaoke club and a family-owned market, according to Woo. But even though that means fewer potential ad buyers for Chang’s paper, Allston is still far from empty of its Korean businesses. A Mexican-Korean fusion restaurant and a popular Korean barbecue chain recently opened near Boston Korea’s office.

“It means [there are] still a lot of students here, but not as many as before,” Chang said. “There used to be a time when Korean students were hanging out everywhere in the streets.”

The small newspaper has a weekly circulation of about 4,300, but it has long stood with an online community of international students as its legs. In 2007, Chang’s paper took off when he merged with an online forum called Boston Korean — a “Korean Craigslist” — which allowed students to buy and sell goods or swap advice on visas and apartments. Just one year after that merge, things were looking positive: Chang was able to move Boston Korea into a larger office and hire his first full-time reporter.

“We had more internet users and we were getting bigger. It was this gateway for Korean students from South Korea who were interested in Boston,” he said.

But in recent years, the number of Korean international students in Massachusetts has steadily declined. Between April 2014 and March 2017, South Koreans studying in Massachusetts decreased by nearly 15 percent, according to data from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Nationally, the decrease was more than 20 percent.

“Four, five or even 10 years ago, there were a lot of Korean foreign students here,” Byung Kim, president of the Korean Cultural Society of Boston, told NBC News. “But we’re certainly getting a flavor that Koreans are not frequenting the Allston area [like] before.”

The prevailing theory between Kim, Chang and several others is that, as the South Korean economy declines, fewer students and parents feel that studying abroad is worth the price.

“We had more internet users and we were getting bigger. It was this gateway for Korean students from South Korea who were interested in Boston.”

“They sacrificed a lot to send their children to the U.S. They make a really big investment, but they don’t get reward. So finally in South Korea, people figured out, ‘No, not anymore,’” Chang said. “If one student comes here, it’s not just one student. So there’s a decrease of whole Korean families here. Right now, they are almost gone.”

Even so, Chang knows that there are people out there who still need his newspaper. The classifieds section advertises some of the only Korean-speaking therapists in the region, and he still gets the occasional hand-written letter from senior citizens in the area.

“I can’t give up the paper newspaper,” he said. “When all the people give up the paper newspaper, then I can finally give up.”

These days, he still makes his Friday morning drive. But now, he’s able to delegate some delivery routes to his small team of reporters. Chang meets them at the Burlington, Massachusetts Hmart – a Korean grocery store chain – and he leaves about 1,300 copies at that location alone for locals to gobble up.

“After the week, there’s none left and it makes me feel so good – it all feels so worthwhile,” he said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.