As those in Maui try to make sense of the wildfires that left behind a trail of loss, experts and activists say the devastation has highlighted the issue of Hawaiian sovereignty.

Those involved in discussions around sovereignty, or the right of a nation-state to govern itself, spoke to NBC News to underscore that the issue has undeniable context for the fires. They include advocates and scholars fighting for international acknowledgment of the Kingdom of Hawaii as an existing nation-state to others working toward complete independence from U.S. interference.

The experts also spoke about the island’s fraught place in American history, which they say allowed corporations to expand and dry out the land in Lahaina, the town most severely devastated by the wildfires in the state. The U.S. claims that a congressional resolution passed in 1898 declared that the Hawaiian islands were “officially annexed.” But some scholars argue the resolution, an internal American law, has no legal standing in the Hawaiian Kingdom and makes American presence an illegal occupation.

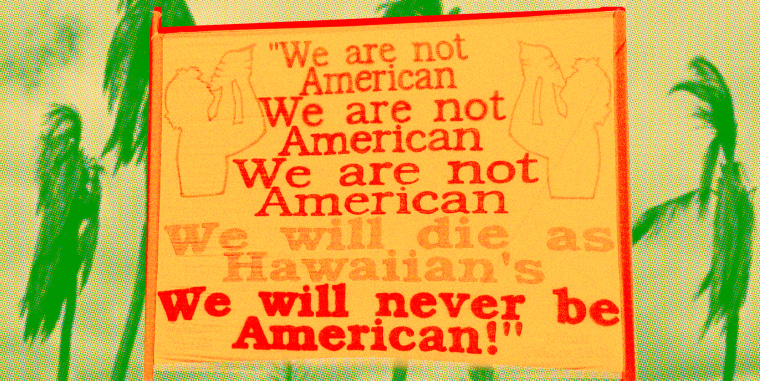

But scholars and activists say that Native Hawaiians have ultimately been seeking their right to self-determination, or decision-making power, on their lands — and that the lack thereof is a root cause of the wildfires. And gaining agency and decision-making power, they add, is critical to healing.

“Lahaina is not America. But that fire is American. And it was really lit as far back as 1893,” said Keala Kelly, a filmmaker and sovereignty activist, referring to when U.S. troops illegally overthrew the Hawaiian queen. “Once the system of governance in Hawaii was stolen from us, everything about land and water became … this never-ending abusive system of theft.”

What do sovereignty and the movement around it mean to you?

Ron Williams, archivist at the Hawaii State Archives: It’s evolved. When Haunani-Kay [Trask, the late leader of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement] was arguing for it, it was a kind of a recognition of Hawaiian sovereignty and breaking away from America. What we’ve come to understand is … how illegal the proposed annexation was. It’s really clear that in 1898, annexation never happened. So if that’s true, then we are left with sovereignty remaining with the Hawaiian Kingdom, which means we’re under occupation.

Keanu Sai, political scientist and founding member of the Hawaiian Society of Law & Politics: I’m not part of the sovereignty movement. That’s a political movement made up of diverse groups of Native Hawaiians. And what they’re doing is they’re pursuing their version of sovereignty, and that is viewing sovereignty as an aspiration, not a reality.

The United States claims that it passed a law in 1898 called a joint resolution, purporting to annex Hawaii. The problem is, an American law could no more annex the Hawaiian Kingdom than the United States Congress passing a law today.

Keala Kelly, activist, filmmaker and journalist: Sovereignty is Hawaiians being self-determining, which is to say we decide our form of self-governance. The U.S. is the perpetrator of the crimes against us, so the U.S. deciding what Hawaiians can and cannot do is like asking the thief if he wants a side of fries to go with everything he just stole from us.

Kaniela Ing, sovereignty activist and national director of the climate organization the Green New Deal Network: Everything needs to be done with an eye toward “ho’omana lahui” — power building, rebuilding the power of our nation, not just a legal status. Questions like, “Who recognizes us as a sovereign kingdom?” That’s less important than that we have self-determination.”

Why are the history and discussions around Hawaiian sovereignty necessary context to the tragedy in Lahaina?

Kelly: This isn’t just a climate change issue, is it? It’s about the destruction of the land and the water, over a century of it, and setting it up for a terrible drought and some hurricane winds, 500 miles away. If that’s going to be discussed, it has to be understood in the context of the theft of our nationhood, which enabled the theft of that land and water.

Will the fires in Lahaina have an impact on action around sovereignty? Will we be seeing a greater thirst to engage in this topic?

Kelly: My sense is, when there is a tragedy here or anywhere else, Hawaiian rights to self-determination are the first thing to be thrown aside, even when it is the most relevant. You can never underestimate the power of fear.

Either we Hawaiians will pull our movement out of the ashes of Lahaina, or our movement for justice will be buried in those ashes, possibly forever.

Williams: The movement towards some sort of reconciliation of what President Cleveland called “An Act of War” by the United States against the sovereign nation of Hawaii has been gaining steam over the past decade, often highlighted by specific issues of injustice like the attempt to build the worldʻs largest telescope atop Mauna Kea. This recent tragedy will undoubtedly offer a significant opportunity for millions to become more educated about the truth of the theft of nationhood, and the truth is the most powerful weapon we have.

Is the topic of sovereignty and self-determination, or decision-making control, critical to Maui’s ability to grieve, mend and move forward?

Ing: When we talk about returning to the old ways, we mean reinstating a sustainable value system, where our nation’s wealth is measured by the health of our land and air and water.

The systems of capitalism and colonialism caused a disaster, and the values of sovereign Hawaii, once exemplified, is the solution to carry us forward.”

Sai: The United States, through the state of Hawaii, as the occupant in effective control of the majority of territory of the Hawaiian Kingdom, is obligated to establish a military government to provisionally administer the laws of the occupied state — the Hawaiian Kingdom.

Right now, there is no centralized control. It’s very decentralized and fragmented between the federal, state and county governments. They’re operating on their own. Maui county has got to deal with the blowback on the recovery. So when you talk about people who are there as victims, the first thing they’re looking at is survival.

The state of Hawaii will be forced to comply with international law by transforming itself into a military government in order to bring centralized control to the crisis that reaches across all the islands and not just Lahaina. Lahaina could be the flash point to drive compliance.