After one of the deadliest wildfires in U.S. history consumed their houses, schools, churches and businesses, the people of Lahaina see the chance for rebirth.

The Aug. 8 inferno left 100 dead and many more displaced and injured. It also claimed over 2,000 buildings and 2,170 acres, including many family homes and structures that were built centuries ago, when Lahaina was the capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom.

But key directives have not been coming from Lahaina. Rather, decisions about the fate of the town are largely in the hands of the state — or with the leadership of the county of Maui. The county says rebuilding the burned structures won’t even begin for another 18-24 months, and big-picture plans are hazy.

After clearing debris and letting people back in to see their homes, the city has most recently opened the remaining schools and welcomed tourists back to areas unaffected by the fires. Officials are working with the federal government to monitor the air, water and soil conditions in the area to ensure reentry is safe.

To rebuild completely, including replacing all of the lost structures, will cost an estimated $5.5 billion.

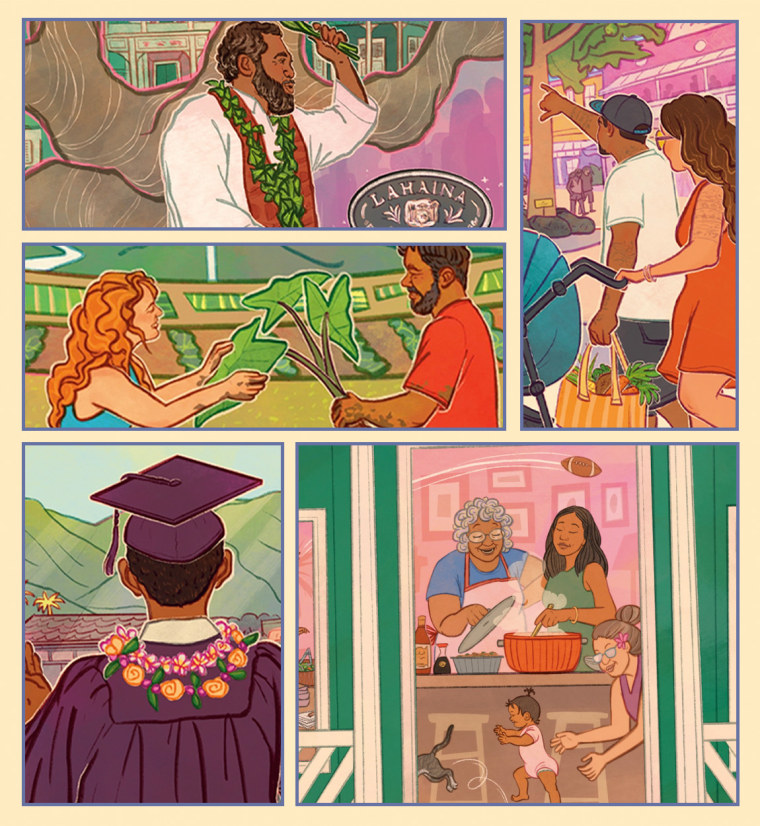

NBC News asked 11 people what their vision of Lahaina’s future looks like. And while the survivors say nothing can make up for what was lost, they hope to rebuild a Lahaina that represents their needs.

A business leader told NBC News that he longs for Lahaina to return to an age of mom-and-pop stores, with a downtown made for locals again; a minister said she wants her burned-down 200-year-old church to once again host the community; and a school principal said he hopes his students, many of whom lost everything, get to grow up in a Lahaina where they want to stay for life.

Here’s how the people of Lahaina see the future of their historic town, one day risen from the literal ashes.

Maui Mayor Richard Bissen: Prioritizing housing, child care and wider pedestrian walkways

Maui Mayor Richard Bissen spent much of his childhood across the street from the town’s famous banyan tree at the hotel where his mother worked. Now, he helms the recovery effort in Lahaina from his office in Wailuku.

His deep roots make it hard for him to imagine Lahaina looking different, but there are some key things he’s prioritizing, including restoring reliable child care and housing.

Right now, the focus is on the community’s most immediate needs, including removing debris, getting people access to their homes again, and restoring utilities and public facilities.

He recognizes the pain of local families and wants to incentivize them to stay in Lahaina. Providing affordable housing, including potentially using funds from philanthropic donations, might be one path. He also wants people to go back to work at the right time for them.

“To really accommodate people, you cannot require them to go back if they’re not ready,” he said. “I think that’s an individual and a personal decision that families make. … Some people lost their homes, they lost loved ones, they lost everything.”

As far as the look and feel of downtown, he pictures it having wider streets, with more foot traffic from local pedestrians.

“It’s hard not to keep picturing Old Lahaina,” he said. “It’s such a beautiful town.”

Minister of Lahaina’s oldest church: Focus rebuilding on the chapel and gathering hall

As the minister of Lahaina’s oldest church, Anela Rosa, 64, says she would see the beauty of the town come to life on Sundays.

“I see people on bikes riding, I see people walking, I see people eating shaved ice,” she said. “I see people playing the ukulele as you’re walking down the road. … I see happy people.”

Waiola Church, which had just celebrated its 200th birthday before fires consumed its three buildings, was the final resting place for some members of the Hawaiian royal family. It was where Rosa conducted Sunday service, weddings, funerals and celebrations. More than that, it was a gathering place for people of all ages.

To keep in touch with her congregation, she has since been offering sermons on Facebook.

She knows Waiola will be rebuilt, she said. But as locals focus on their immediate needs, the planning seems far off. She doesn’t know how it might look, but she knows she wants to bring back at least two buildings: a chapel and a community gathering space.

“There’s not even a doubt that we’re going to rebuild the church,” she said. “I think it’s important that, in addition to our church sanctuary, that we also have a social hall. For gatherings, for community meetings, for birthday parties, for celebrations, weddings. It did play a big role.”

A principal and school leader: Keeping the next generation local

As the heads of a West Maui school now filled with students and faculty who lost everything, Miguel Solis and Ryan Kirkham want to see a Lahaina built for their kids to thrive. They hope young people’s needs are placed at the center of reconstructing the Lahaina they’ll grow up in, including spaces for them to use technology, innovate and start new enterprises without having to leave the area.

“There’s a real movement to not re-create it, but modernize it and rebuild it in a way that still honors its history,” said Kirkham, who is the principal of Maui Preparatory Academy.

Solis, the head of school, imagines a thriving economy with ample work and affordable housing that keeps locals, especially Native Hawaiian families, in Lahaina.

“These are the people that carry with them the language, the history and the storytelling. … This is their homeland,” he said. “I don’t want them to leave. I want them to stay here. But that’s going to be so difficult if they don’t have homes, if they don’t have jobs.”

With classrooms set up for the first day of school, the small K-12 building took in around 700 survivors the night of the fire. Families were bused in by the dozen, some soaking wet or covered in ash. Over the next few days, Kirkham and Solis distributed donated supplies to thousands.

As the smoke cleared, it was revealed that King Kamehameha III Elementary in Lahaina had completely burned down. Lāhaināluna High, Lāhainā Intermediate and Princess Nāhi‘ena‘ena Elementary survived the flames, but could not open due to the air and water quality.

When Maui Prep finally welcomed kids back two weeks later, its student body had grown from 275 to 390. Displaced children from all over Lahaina joined its ranks. It’s been a challenge, Kirkham said, as everyone contends with loss. Their focus now is on providing a space where the students can begin to thrive again.

“We didn’t hit the books hard right away. We were just trying to give some sense of normalcy to our returning students, and then introduce the new students,” Kirkham said. “In some ways, I feel as though we’re just barely past the, ‘OK, do we have a roof over our heads? Are we safe for the next couple of months.’”

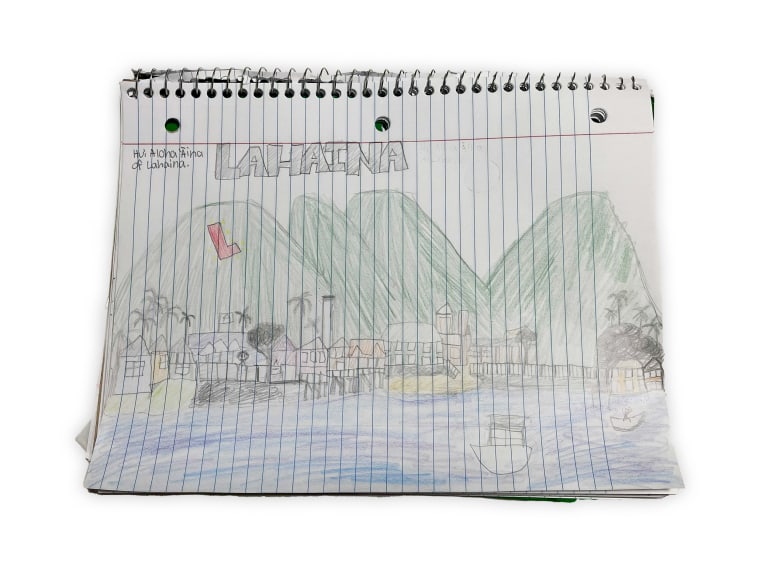

A middle schooler: Worried about having a future ‘road to escape when there’s a fire again’

Francheska Vhiel Balete Misay, 12, has been displaced, bouncing around temporary housing in hotels since August. The fires have affected her so much that the main thing on her mind is safety — in case there’s a next time.

That’s why the seventh grader, who grew up in Lahaina, said she’s hoping that her hometown will be rebuilt with safety as a priority.

“I want it to be the old Lahaina again but more safe,” she told NBC News. “The fire has been a lesson for us. … We would have more roads to escape when there’s a fire again, the community stronger, and we can build it together.”

She also envisions more robust safety measures at school, including more evacuation drills and a higher level of training for students and staff to contend with fires and other climate disasters.

Francheska said she was visiting relatives in the Philippines when the fires broke out. Since her family returned to Hawaii, they’ve been floating the idea of moving to another state. The possibility of leaving her hometown, she said, is devastating.

“The last time we were in my house was the day we left to the airport,” she said. “Whatever we packed in our suitcases is what we have left.”

The fires have undoubtedly shaped her, she said. While she has always dreamed of becoming a doctor or lawyer, she said she’s more motivated now than ever, hoping she can help her community in the future.

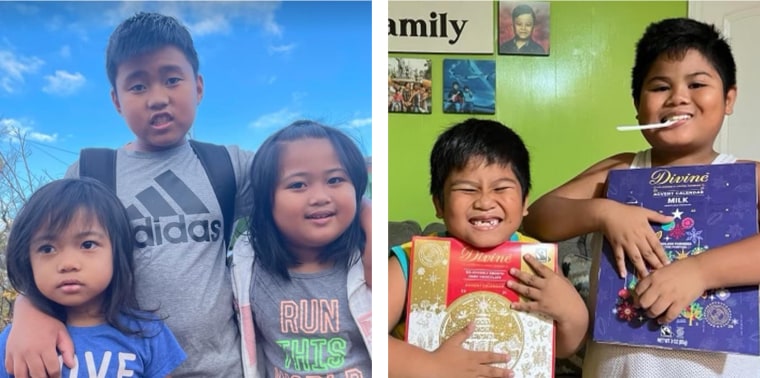

A Filipino immigrant whose family of 50 was displaced: Hope for more multigenerational housing

Camille Serrano, 51, said healing has been difficult since the fires left the more than 50 members of her immediate and extended Filipino American family separated and away from their usual home base.

“I’m just trying to survive one day at a time, just going through the motions,” she said.

Serrano, a longtime Lahaina resident who came to the U.S. from the Philippines in 1999, says she hopes the area can be rebuilt with more permanent, multigenerational housing available for Filipino families like hers so they are able to maintain their communal lifestyles. She explained that spending time with loved ones and relatives is a critical part of both joy and grieving in the Filipino community.

“We want our next generations to be as close and family-oriented as we are,” she said.

Serrano, who lived with her mother and children only a 5-10-minute drive from several of her siblings, said she longs to revive their family rituals.

“We used to have a Sunday brunch, just to have a family get-together, cook out. If it’s not at the beach, it would be at my mom’s house, which is my house,” she said. “After mass we just do that, and all the grandkids would come and they love doing karaoke like a typical Filipino.”

The scattering of her loved ones across the island, in addition to the housing uncertainty they all currently face, has taken a toll, she said.

“We are very close,” she said through tears. “I’m a very, very simple person. I would just like to see how it was before.”

Preservationists restoring Hawaiian Kingdom-era structures: Hopeful about rebuilding on top of former king’s lava rock and coral foundations

Throughout Lahaina, there are vestiges of King Kamehameha III’s openness to a diversity of architecture. The oldest house on the island of Maui, the Baldwin House, for example, wasn’t only made of wood. Its walls incorporated stone, crafted from coral and lava rock. Some of these structures from the Hawaiian Kingdom, which lasted from 1795 until 1893, can be restored due to the king’s architectural vision.

Kimberly Flook, deputy executive director of the Lahaina Restoration Foundation, a nonprofit aimed at preserving and protecting Lahaina’s history and cultural heritage, said she’s hoping that many of the important historical structures are salvaged.

“Some of the buildings from every era, their bones are still there. And that means they can be restored,” Flook said. “That doesn’t mean that we didn’t lose probably five- to seven-hundred other buildings that were wooden that did not have stone elements, but it does mean that pretty much every [historical era represented] throughout town, we have the ability to continue to interpret these time periods.”

Among the historic structures that still stand are the Lahaina Customs and Courthouse, which once served as the center of the Hawaiian Kingdom, and the Masters Reading Room, a sort of gentlemen’s club retreat used during the Missionary Era.

Restoring the structures will likely call for a large investment of time and money, Flook said, requiring the help of architects, engineers and construction groups that specialize in historic restoration projects. She added that the structures will likely be rebuilt with the same materials that were historically used, aside from areas that could be improved to account for climate change. That means the majority of the buildings will still have old materials including coral and lava rock, lime mortar, shingled roofs and wooden floors and staircases, in addition to newer materials approved for restoration.

But Flook said she’s ultimately prepared to support what Native Hawaiian leaders deem to be the best way to preserve the Hawaiian story.

“It’s important to really bring what we call the ‘host culture,’ the Hawaiian culture to the forefront. Now more than ever,” she said.

A business owner: Returning to a mom-and-pop Front Street

A Filipino immigrant, business owner and community leader, Rick Nava, 64, has been in Lahaina for most of his life. When he pictures what the restored town might look like, he’s more inclined to look back than to look forward.

Since the Aug. 8 fires, 600 Maui businesses have shuttered, according to data from the Hawaii Small Business Development Center.

He hopes Lahaina will be rebuilt in the image of the one he grew up in — made for the local community. He envisions Front Street lined with mom-and-pop stores and the town teeming with Hawaiians again.

“Right now, most of the shops there are catered to the visitors,” he said. “These last few years, the only time we go to Front Street is if we have a friend that’s visiting Lahaina. …The parking is terrible, and when you park you have to pay for it. It’s just not convenient to be there.”

Nava watched flames start to lick his roof as he fled a burning Lahaina in August. His house burned, and he’s spent the last few months on the other side of the island — away from the place he’s called home since he was 10. Bringing people back into town, he said, is the only way forward.

Serving on the mayor’s advisory council, assembled in the aftermath of the fires, he has floated ideas like temporary modular houses aimed at bringing people who lost their homes and fled to shelters back to Lahaina.

“Housing is to us a priority. Everything else will fall secondary,” he said. “We need to have people back.”

The Tourism Authority: Pushing for increased agrotourism, allowing tourists to give back on their trip

The Hawai’i Tourism Authority says the future could be greener and more charitable.

Ilihia Gionson, the public affairs officer for the Hawaiʻi Tourism Authority, said in October that officials will help establish more agrotourism opportunities, where visitors get to experience the surrounding agriculture while generating income for the farmer or business owner.

Gionson said this could mean, for example, helping to restore or maintain traditional Hawaiian fish ponds, where visitors can also eat the fish later that day.

“How can we circle around that farmer to help build some sort of experience where that then helps the profitability of the farm, helps that farmer employ more people, helps that farmer grow more food?” he said.

Gionson said that tourism is a significant part of the local economy, with roughly 40% of the jobs on Maui supported by visitor spending. Within the first six months of 2023, 1.5 million visitors to the island spent $3.5 billion. However, he said, he’s aware of the criticisms around the presence of tourists in a Lahaina that’s still contending with housing issues and securing basic needs.

“Tourism is definitely a big part of life on Maui as it is right now. Whether or not that continues to be in the future for that region is up to the people of Lahaina,” Gionson said. “Right now, they’re still grieving. They’re still recovering. Before anyone gets into any specifics about rebuilding anything, the most important part is supporting and uplifting the people of Lahaina.”

A state rep: Aiming to restore faith in local government

Representing Lahaina in Hawaii’s House of Representatives, Elle Cochran moved back to her home in town just a day after the fires and hasn’t left since. Helping to coordinate relief efforts in the following weeks, she says she’s seen exactly what her Native Hawaiian community needs.

“A lot of people have just lost faith in government right now,” she said. “Myself being one of them, and I’m a state rep.”

As a representative and a Native Hawaiian herself, she says she’s working to restore some of that faith. To do so, she wants Lahaina residents to be in charge of their own healing. They should recover at their own pace, she said, without the pressures of returning to work and serving tourists looming over them.

“Are our people ready to go back and service guests? Put on the happy face and be Mr. and Mrs. Aloha? No, not at all,” she said.

Opening should be slow, she said, and follow the needs and readiness of residents. Everyone from the state to the county should be more communicative and attentive to local needs, too, she said.

The governor didn’t consult with the local representatives before making the decision to reopen West Maui on Oct. 8, Cochran said. Along with Lahaina’s state senator, Cochran sent Gov. Josh Green a letter urging a delay in the opening, but she said she got no response.

Green’s office did not answer NBC News’ questions about his communications with locals during the disaster, but directed focus to the governor’s press conferences after the fires.

“He just pretended like it never happened, didn’t say one thing,” Cochran said.

She wants to see her city rebuilt for the locals she represents, coming back stronger and more sustainable, with a renewed focus on farming. She envisions small farms, native plant life and ulu trees decorating the hillsides behind Lahaina and family businesses at the forefront.

A local mom of a 1-year-old: Just trying to give local kids a nice Christmas

For Caitlyn Kuskowski, 29, no experience can compare to that of raising her baby in Lahaina’s community of moms. After the fires damaged her home and she was forced to return to her parents’ house in Michigan, she said, she has just been trying to create some normalcy for her 1-year-old son — and kids who lost much more.

“It was a very small-knit community, and everyone was so quick to help you out,” she said.

Though now an ocean away, she wants that sense of togetherness to persist, so she started a program to provide Christmas gifts for displaced Lahaina children.

On her Facebook group “Adopt a Lahaina Keiki,” 300 families have already been placed with sponsors who will buy gifts from their Christmas lists. Kuskowski is coordinating getting those gifts to the families, whether they’re at a hotel, a shelter or a relative’s home.

“It’s really humbling to see how simple these children’s wish lists are,” she said. “Because they have been affected so much over the last few months. A lot of clothes, journals, a little camera … just things that they had before.”

Knowing many are in a worse position than she is on the mainland, she says she wants to keep Lahaina’s spirit alive for her son and other kids who will grow up there.

“These children are only little for a little bit of time,” she said. “I hope that they can continue to grow up in a community that instills aloha and instills a life of simplicity and gratitude.”