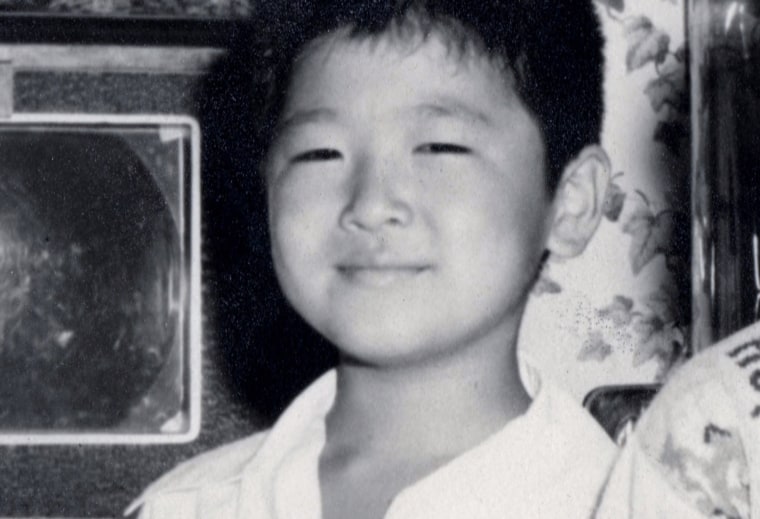

Born in a Japanese-American internment camp during World War II, criminal defense attorney Mia Frances Yamamoto has always known the effect that race can have on justice, and she often jokes to both audiences and clients, “I was born doing time.”

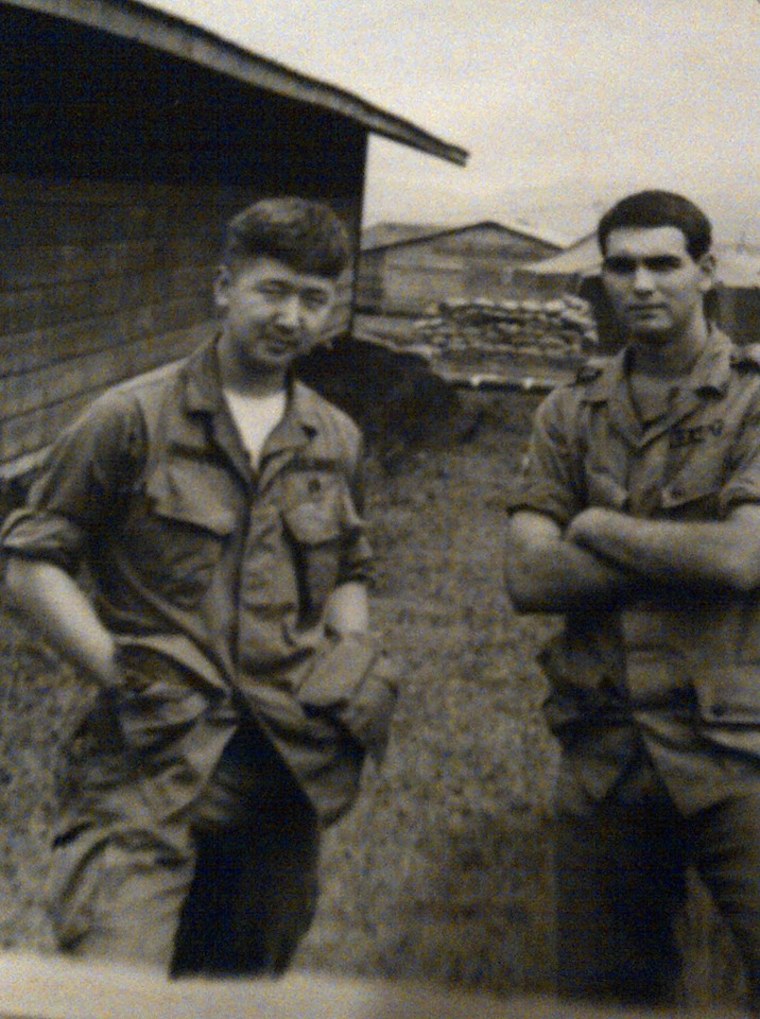

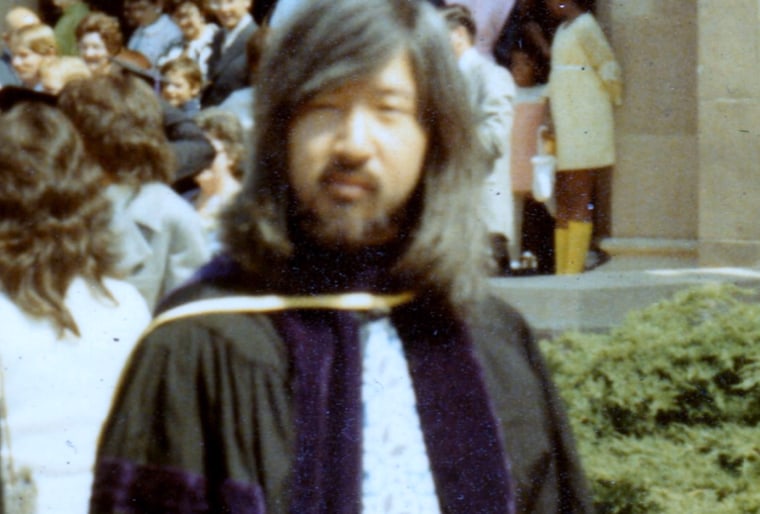

That kind of tough talk, contrasted against the glamour of her shoulder-length, shocking-white hair and easy smile, brings a poignancy to Yamamoto’s story. Born Michael, Yamamoto served in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, attended UCLA Law School, co-founded the Asian Pacific American Law Students Association, worked as a public defender, then opened a private practice—all while struggling with gender dysphoria, the sense that she was born the wrong gender. After years of therapy and depression, she realized that she needed to tell the truth about who she was and decided to transition. As a testament to her work and reputation, every single one of her clients chose to stay with her rather than switch attorneys.

A leader in Asian Pacific American, LGBT, and legal communities, she has tried over 200 jury trials and represented thousands of clients accused of criminal offenses, including murder, assault, sex offenses, drug offenses, theft, white-collar offenses, and regulatory offenses. She has won a slew of awards and honors, and served on two California Judicial task forces and a Presidential Initiative.

“Mia Yamamoto is such a personal inspiration,” said UCLA law student Lindsey Shi. “To me, she represents the struggles and successes of both the [Asian Pacific American] community and the LGBT community. Not only is she a great role model, it's clear that she really loves giving back to students as well...she's always willing to lend an ear and a shoulder to anyone who needs it.”

Yamamoto recently took some time to talk with NBC News about her identity, her work, and how the two intersect.

How do your early life experiences tie into your civil rights activism?

I was born in Poston, Arizona, which was one of the concentration camps wherein people of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated during WWII. My mom was a registered nurse and my dad was a lawyer (Loyola Law School, class of 1932) who went around the camp telling people that they couldn't do this to us - that he had read the Constitution and you couldn't just throw people in jail because of their race. Of course, he was wrong. And I was reminded of my dad when I was stationed in Vietnam during the war and I read a biography of Ho Chi Minh, who had also read the Constitution and wrote to President Truman, believing that America would surely take their side against the attempts by the French to re-colonize Indochina. Neither my dad nor Ho Chi Minh understood how much race matters.

What about your own experiences with race and identity - how do they color your work as a criminal defense attorney?

When we got out of camp, my dad resumed his law practice which excluded him from the Whites-only Los Angeles County Bar Association; and he practiced in the segregated bar for his entire career until he died in 1957. So, I am able to reassure my clients that I understand how people get targeted and jailed because of their race, since I was actually born doing time because of my race. I've witnessed much racial discrimination; and my sympathies are with people of color who spend their lives coping with racism, racial exclusion and racial violence. Being a criminal defense attorney means a great deal to me because of this.

What do you think is the role of the Asian-American community in racial inequality issues, such as police violence in Ferguson and Baltimore?

It is the role of Asian Americans to repudiate the myth of the model minority and to lend their voices and their bodies to the struggle for the lives and futures of communities of color. Neither Ferguson nor Baltimore will be the last eruptions of rage, resentment and resistance. The oppression and marginalization which has characterized the treatment of poor people, especially people of color, will continue to foster upheaval. Nothing will change until the promise of equality and justice is somehow fulfilled.

How do you think Asian American and LGBT issues intersect?

I think that Asian American and LGBT issues are inextricably intertwined (did I really say that?) in that those of us who live at their intersection witness a wide spectrum of bigotry with which we have to cope and overcome in order to fight for the communities we represent. These challenges are unique to any person who is born into multiple cultures and ethnicities; and they provide us with multiple opportunities to advocate, educate, and eventually liberate. All these things that I grew up considering curses have turned out to be blessings.

What is your message to young Asian Americans struggling with identity issues or whether to get involved in civil rights activism?

I hope my message to young Asian Americans, who are struggling with identity issues, will be that the battle for the rights of the oppressed and downtrodden among us is still the most noble challenge we can undertake to overcome, because, not only does it serve to liberate us personally, it liberates all those like us and, ultimately, all of society. It has to be for all of us or it is meaningless. Social justice should trump self-interest. We are uniquely situated to carry that message to our own communities and to the rest of our nation.

Anything else you would like to get out there?

I would ask that we all look beyond our own little community and even our own nation out to the world beyond America, to both learn from and to lend a hand against torture, genocide and fascism. Join in the international struggle for worldwide human rights. Look up International Bridges to Justice at www.ibj.org and consider donating to the cause. We can do so much to alleviate the unjust and inhuman suffering that is inflicted upon so many, not just here, but everywhere.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.