After Vivek Ramaswamy’s explosive performance at Wednesday night’s Republican presidential debate in Milwaukee, experts say it’s clear that his star is on the rise. But on that ascent, they warn, the tech millionaire is feeding dangerous ideas about immigration.

Standing near center stage, Ramaswamy drew the most incoming fire from his fellow candidates. While he used little of his time to talk about his personal background, experts noted that his parents’ immigrant story became a tool for him at some key moments.

“My parents came to this country with no money 40 years ago,” he said in his opening. “I have gone on to found multibillion-dollar companies.”

It’s rhetoric that has long been used on the right, even by some of Ramaswamy’s contemporaries, like GOP candidate Nikki Haley, to paint a picture of Asian immigrants as inherently successful and hard-working, especially compared to other minority groups, said Karthick Ramakrishnan, the founder of AAPI Data, a nonprofit policy and research group.

“Ramaswamy has a very selective reading of the immigrant experience,” he said.

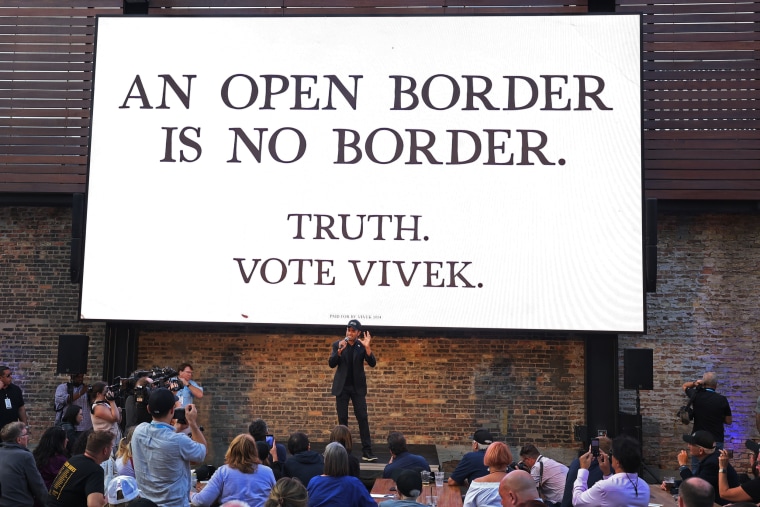

Especially notable, he said, was the way Ramaswamy went on to lambaste undocumented migrants’ crossing the southern border, which he described as an “invasion.”

“We will close the southern border where criminals are coming in every day,” Ramaswamy, 38, said at the debate.

While that language isn't new to the GOP playbook, Ramaswamy has at times gone further than some of his rivals. He advocated for getting rid of lottery-based visas in favor of “meritocratic admission.” He has also advocated for the use of military force to secure the border. Coming from a brown person and a child of immigrants, it paints a distorted view of the U.S. immigration system, Ramakrishnan said.

“There’s this notion of the good immigrant versus the bad immigrant, the people who came here the right way versus the wrong way,” he said. “Our immigration system is fundamentally broken. Adult relatives of immigrants from India have to wait 20 years or more to get their visa.”

Ramaswamy’s senior adviser and communications director Tricia McLaughlin doubled down on his statements.

"Yes there is the right way to enter the country (legally) and the wrong way to enter the country (illegally)," she told NBC News. "That’s not a myth or stereotype. That’s fact."

Though rhetoric like that might help bolster Ramaswamy’s performance in the Republican field, it doesn’t paint a full picture of the complexities of immigration to the U.S. — even South Asian immigration, he said.

“Yes, most Indian Americans came to the United States on employment-based visas and family visas, but Indian Americans have a sizable undocumented immigrant population in the U.S., and that’s important to acknowledge,” Ramakrishnan said. “Indian immigrants have tried to cross the border because of how difficult it is to come in through family visa sponsorship.”

Terms like “invasion” have been rising in popularity on the right since Donald Trump’s presidential campaign in 2016. Ramaswamy, who closely aligns himself with the former president, is riding a harmful nationalist wave, immigrant justice leaders say.

Using terms like “invasion,” an expert said, inherently feeds white supremacism.

“It is deeply distressing to see that a child of immigrants, himself a person of color, would be lifting talking points from neo-Nazis,” said Kica Matos, the president of the National Immigration Law Center. “It legitimizes that kind of dangerous talk. It gives a sense of normalcy and permission for white supremacists to advance their deeply repulsive beliefs.”

Matos said it’s hard to watch candidates whose parents came here to give them better lives actively work to stop others from doing the same for their kids.

“It seems like this is a real example of them pulling up the ladder behind them,” she said. “They benefited from opportunities offered to immigrants, and now … they are stomping on other immigrants.”

Pawan Dhingra, a professor of American studies at Amherst College, said: “I think he accomplished his goal of being talked about a lot. In some ways, it could make him an endearing candidate to a lot of Republicans. It’s his way of saying, ‘Listen, we’re not anti-immigrant; we’re anti-some immigrants.’ And by endorsing someone with an immigrant background, they’re able to wrap themselves in a sense of self-confidence.”

South Asian Americans are a very small slice of the Republican voter base, Ramakrishnan said, and the candidates who share their ethnicity — Ramaswamy and Haley — haven’t had a reason to speak directly to them yet. But in addressing his ethnic origin to the white majority of the party, Ramaswamy has a specific goal in mind, Dhingra said.

“He’s not looking for embracing diversity,” Dhingra said. “He’s very nationalist. … It’s designed, in my mind, to kind of say, ‘Listen, I’m your kind of immigrant.’”