After waiting nearly a decade, Jin Ming Cao still hasn’t seen his money.

Cao, a 36-year-old former waiter in Manhattan, had joined some of his co-workers in 2008 to sue their employer, a popular New York Chinese restaurant, Wu Liang Ye. The charges included failure to pay minimum wage and overtime.

But on the eve of trial the following year, Wu Liang Ye closed its two restaurants, according to court papers. And after an attorney who represented the restaurant withdrew from the case, the manager who was his contact with the company “disappeared and was never heard from again,” the lawyer said.

A federal judge ultimately sided with the waiters and take-out delivery workers, awarding 24 plaintiffs a total of around $1.5 million in damages. Cao himself is owed more than $140,000.

“But I cannot collect even a penny,” Cao, a father of two, told NBC News.

While it may be too late for Cao, the Securing Wages Earned Against Theft (SWEAT) bill would provide wage-theft victims a legal tool to chase down money owed to them — a lien to temporarily freeze an employer’s assets.

The bill, versions of which have been introduced in previous legislative sessions, have passed both the New York Assembly and Senate ahead of the end of this year's legislative session, slated for Wednesday.

A PERVASIVE PROBLEM

Hardly unique to New York, wage theft can affect anyone and comes in a variety of forms, including minimum wage violations, failing to pay overtime and not paying workers the difference between their tips and the legal minimum wage.

In the 10 most populous states, workers lose $8 billion a year from minimum wage violations, according to a 2017 report from the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank.

It’s a form of wage theft that can cause families to drop below the poverty line, increase reliance on public assistance and hurt state and local economies, the report said.

Workers recovered $2 billion in stolen wages in 2015 and 2016 through the efforts of the U.S. Department of Labor, state departments of labor and attorneys general in 39 states and class action settlements, according to a separate Economic Policy Institute study.

But “these recovery numbers likely dramatically underrepresent the pervasiveness of wage theft,” the report notes, adding that low-wage workers are estimated to lose more than $50 billion annually.

REMEDIES

At least 10 states, including Maryland and Wisconsin, permit workers to put a lien on an employer’s property in connection with a wage claim, according to a 2015 report by the Legal Aid Society, Urban Justice Center and the National Center for Law and Economic Justice entitled “Empty Judgments: The Wage Collection Crisis in New York.”

Generally, a lien is the right to keep possession of property that belongs to another person until a debt owed by that person is paid.

While New York does have a lien law, dating to the early 1900s, it applies only to certain workers in the construction industry. Expanding it to cover all workers, the authors of the 2015 report argue, would place New York on par with other states that have enacted wage liens.

“A wage lien not only encourages an employer to dispute the matter and play fair in court, but ensures that if the workers win their case, they may actually be able to enforce a judgment against the employers’ property and collect the wages they are owed,” the report notes.

To use the lien, the proposal would require employees to show in court that they are likely to win a wage-theft case. After doing so, the court temporarily attaches the employer’s property so workers can collect if their case is successful, according to a statement from Democratic state Assemblywoman Linda B. Rosenthal, SWEAT’s sponsor in the Assembly.

“The bill does not create any new liability or responsibility, but instead streamlines the process and helps to balance the scales of justice in favor of aggrieved employees,” Rosenthal said.

But there is opposition.

The New York City Hospitality Alliance, a broad-based membership association representing restaurants and nightlife establishments across the city, argues the bill would permit any disgruntled employee to file a lien based on “mere allegations.”

Among other criticisms, the group said SWEAT would also freeze credit on small businesses and increase bankruptcies by employers and individuals seeking to get rid of the liens.

“While the Alliance takes wage theft extremely seriously — and recognizes the proposal’s positive intentions — the bill as drafted would have serious negative consequences on small businesses and employment in New York State,” the group said in an April 30 memorandum of opposition.

Sarah Ahn, director of the Flushing Workers Center, a workers advocacy organization, said that when workers attempt to recover back wages, unscrupulous employers may transfer assets, change the name of their shop or sell their homes to relatives on the cheap to avoid having to pay up.

“It just becomes a chasing game,” she said.

The SWEAT bill, Ahn explained, would help by freezing assets until the investigation or court case concludes.

“It doesn’t mean the worker has access to that money," she said, just that the employer can’t yet transfer it yet.

In the meantime, worker advocates have used New York’s state fraud law to go after an employer’s assets.

Jackson Chin, senior counsel at LatinoJustice PRLDEF, called it “an unprecedented legal approach” that his organization, the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund, and Shearman & Sterling LLP took against a Korean restaurant owner in New York City.

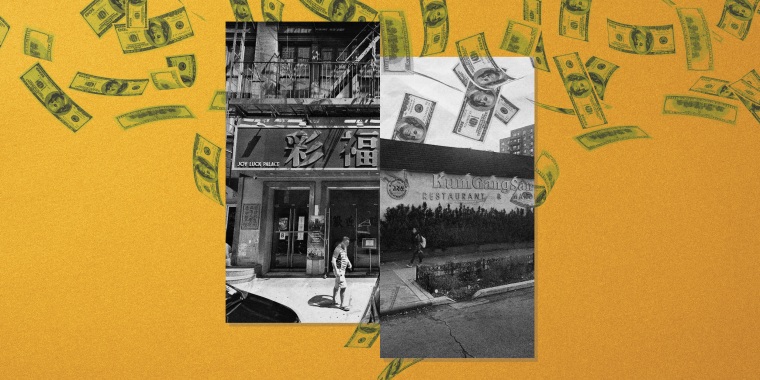

A three-judge panel of the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals recently affirmed a lower federal court’s ruling that the owner of Kum Gang San had fraudulently transferred his interests in three properties to family members to avoid having to pay a nearly $2.6 million wage-theft judgment to workers.

Emails and phone calls to the law firm representing the restaurant owner requesting comment were not returned.

SHOW ME THE MONEY

Cao, meanwhile, is still waiting on his $142,812.05, he said.

The complaint against his former employer said that the more than 20 plaintiffs worked five to seven days a week, four to 12.5 hours a day. They were also regularly made to work before or past their scheduled hours and not paid for the additional time, the suit said.

The workers earned a monthly sum of $300 to $1,900, which amounted to an hourly wage that fell below the minimum required by the Fair Labor Standards Act and New York Labor Law, according to court papers.

Judge Denny Chin, who oversaw the case, subsequently entered a default judgment against the defendants, noting in an Oct. 8, 2009, filing that they closed two of their restaurants on the eve of trial. (Another Manhattan restaurant named Wu Liang Ye remains open, but was not a party to the judgment.)

The plaintiffs later submitted their proposed figures for damages, to which the defendants failed to object, court records show. In the end, the workers were awarded about $1.9 million in damages and attorney's fees.

Peter Contini, the attorney who represented the restaurant and its owners, said in an email that as the case approached trial, his clients ran out of funds and he had to withdraw as their lawyer.

“Before that, with the assistance of the judge in the case, we tried to convince the plaintiffs to settle by taking a settlement which would be paid out in installments,” Contini wrote. “I’m pretty sure the amount was $300,000 and the payout was over a three-year period, but I’m not positive. That was all my client could afford and it was a last-ditch effort to save the business while compensating the plaintiffs.”

Contini added that before he stepped down, the business had met with a bankruptcy attorney, though he doesn’t believe it filed for bankruptcy.

“I really have no knowledge as to what happened to the assets of the business,” he said.

Cao alleged to NBC News that the owners reopened under a different name. He said he hasn't been able to collect his judgement because they cannot prove they're run by the same owner.

Cao, an immigrant from China, eventually took another job as a waiter at the Joy Luck Palace in Manhattan’s Chinatown. He is again a plaintiff in a separate federal suit, filed in January and joined by 18 other workers, accusing the restaurant of minimum wage and overtime violations, among other things.

Joy Luck Palace reportedly closed as a restaurant in February 2018 and turned into a banquet center, according to Eater New York.

It wasn’t immediately clear whether the defendants had hired a lawyer. Attorney information was not listed in the electronic docket. Joy Luck Palace has not responded to the complaint, and a proposed default judgement for the plaintiffs was filed this week.

Attempts to reach the restaurant by phone were also unsuccessful. A number associated with Joy Luck Palace was not in service.

These days, Cao said he works as an organizer for the Chinese Staff and Workers’ Association. He said wage theft remains a big problem in New York City, adding that he hopes the SWEAT bill is signed into law.

“It’s easy to get a judgement, but we cannot get the wages back,” Cao said.

Follow NBC Asian America on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr.