The minute Alabama jail guard Jeremiah Van Horn laid eyes on inmate Phillip Anderson, he said he could tell the 49-year-old veteran was grievously ill.

"This man was literally in a ball, moaning and groaning," Van Horn told NBC News this week. "I was shocked to see him lying there like that."

In the ensuing hours, Van Horn said, he repeatedly tried to get help for Anderson but was told that medical staff at the Tuscaloosa County Jail believed he was faking.

Van Horn, though, said he had no doubt Anderson's suffering was real.

"He was in excruciating pain," Van Horn said. "I started praying, 'Oh Lord, can you see what's wrong?'"

At the end of his overnight shift, Van Horn went home. Hours later, everyone agrees, Anderson collapsed and was taken to the hospital, where doctors rushed him into surgery and discovered a perforated ulcer. He died on the operating table.

Afterward, Van Horn said, a supervisor had him write out a statement about his contact with Anderson — then tore it up and had him submit a new one with less detail. An attorney for the jail told NBC News that he didn't believe that happened.

Anderson's death is now the subject of a lawsuit by his family. And in a surprising move last week, the federal government — which funds and provides legal coverage to the jail's non-profit medical provider, Whatley Health Service — admitted liability.

Although the feds denied specific allegations of wrongdoing in the suit, the move means the only thing they will contest at trial is how much in damages they have to pay, according to a motion they filed.

I started praying, 'Oh Lord, can you see what's wrong?'

Some defendants — the county, the sheriff and a deputy — were removed from the suit by the court during pretrial proceedings. But the judge declined to dismiss claims against two jail officers, Sgt. Kenneth Abrams and Patrick Collard, finding they "had a duty" to get a sick inmate help, a ruling they plan to appeal.

"If he hadn't been in jail, he would be alive right now," said Anderson's daughter, Erica Fikes, 29. "I don't feel like they even gave him a chance."

The lawsuit is one of many that have been filed across the country accusing prisons and jails of denying inmates adequate medical care.

"There is a public health crisis in this country of people behind bars not getting medical, mental health or dental care that they need," said Gabriel Eber of the ACLU National Prison Project, which is not involved in the Anderson matter but has gone to court to force improvements at other lockups.

"It's a crisis that causes [people] to suffer immeasurably and occasionally even to die as a result."

The attorney representing Anderson's family, David Schoen, said his death "was the direct product of a system that treats an African-American citizen of modest means as something less than human.

"Only now, three years later has the federal government on behalf of the medical staff admitted their role in causing Mr. Anderson's death," he said.

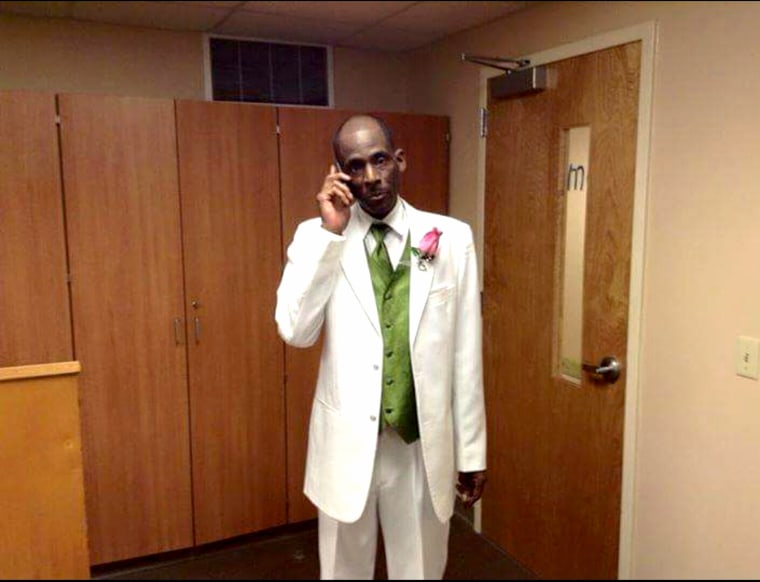

Anderson, a former Army reservist who had four adult children, was arrested on Feb. 7, 2015, after police at a roadblock discovered an outstanding warrant for a contempt of court charge from an old child support case.

According to the suit, Anderson fell ill soon after being booked into the jail, vomiting after a meal. Unable to keep down food or move his bowels, he was treated for pain with naproxen — which can cause or worsen ulcers — and then for constipation.

By Feb. 13, Anderson's condition had gotten much worse, according to statements from fellow inmates included in the court file.

"This man hollered for three days straight, all night long," one of the inmates, Gaffery Buggs, told NBC News. "This man was really hurting."

But another inmate, Eric Ligon, said in a statement for Schoen that jail staff accused Anderson of malingering, yelling at him to get up.

By Feb. 14, Anderson's stomach was badly distended and hard to the touch, Ligon said. He couldn't get out of bed and groaned all the time.

That was the situation Van Horn said he encountered when he went to cell block 11 that night for a head count. He said he called his sergeant to say Anderson needed to go to the infirmary and was told he'd already been assessed and was being treated.

"I called every 30 minutes until I was told to stop calling," said Van Horn, who said he left his job for medical reasons and has a pending employment discrimination lawsuit against the county.

Eventually, he said, a Whatley nurse called for Anderson, who was brought to her in a wheelchair. The nurse, according to Van Horn, "said she can't send him out to the hospital because she will get fired."

She gave Anderson an enema and sent him back to the cell. The doctor, Phillip Bobo, wouldn't be able to see the inmate until Monday, she said. But by then, it would be too late.

The morning of Feb. 15, Anderson's family, alerted to his condition by other inmates, called the jail to say he needed medical assistance. The two detention officers, Abrams and Collard, went to check on him and later said in statements that the sick man took off running toward the bathroom and fell on his way back to the bunk but was able to jump up without assistance.

Their account was disputed by other inmates who said Anderson was in no shape to do anything but plead for relief.

"Mr. Anderson kept asking me to help him somehow," inmate Kenneth Brifford said in a statement for Schoen. "He thought he was going to die."

Barely two hours later, according to the inmates, Anderson passed out while being helped to the bathroom. They said a nurse summoned to the cell accused him of faking and had them lay him on the ground in a pool of urine.

Jail staff tried to resuscitate him with a defibrillator before EMS arrived and took over. He arrived at the hospital three hours after he collapsed, according to a defense expert's timeline.

A medical expert hired by Schoen concluded that Anderson's death was preventable and that medical staff "neglected obvious and ominous signs of his worsening health." The expert, Dr. Homer Venters, said even a layperson would have recognized that Anderson needed to go to the emergency room for testing.

Travis Wisdom, who represented the county, the sheriff and the jail employees, said it's unfair to blame the detention officers for Anderson's death when the medical workers misdiagnosed him.

"Do we want untrained people overruling professional doctors in our society?" Wisdom said, adding that Anderson and Collard only had contact with Anderson on the last day he was alive. "Our records show every time he requested treatment, he was given treatment."

Do we want untrained people overruling professional doctors in our society?

"Unless every jail guard happened to be sadistic, what motivation would they have to deny this man medical attention?" Wisdom added. "It doesn't cost the jail or the county more money to treat him."

The U.S. Health Services and Resources Administration, which funds the Whatley clinic, said it could not comment because the lawsuit is ongoing. Whatley did not return a call for comment, and Dr. Bobo — who used to treat the judge's family and had also treated Anderson before he was jailed — also did not respond to a request for comment.