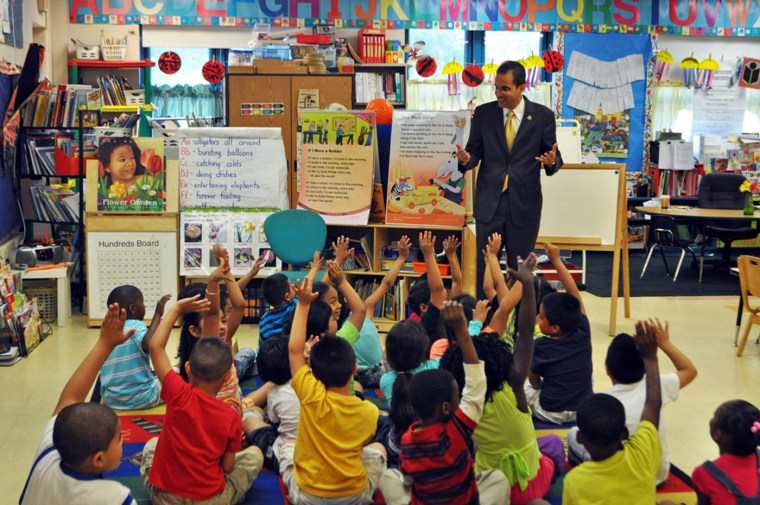

For Angel Taveras, Rhode Island's first Hispanic mayor, improving the Providence public school system is personal.

"I know that education is the path out of poverty. I’ve traveled it. I’ve lived it," said Taveras, the son of Dominican immigrants, who attended a Head Start program as a kid.

On February 3rd, Taveras announced the launch of Providence Talks, a program designed specifically to help low-income parents prepare their children for school by shrinking the “word gap."

While children of high-income families hear up to 20,000 words a day, children from low socio-economic status families hear significantly less, some hearing as few as 600 child-directed words. A child in a low-income household has heard 30 million fewer words by his or her fourth's birthday than a child from a higher-earning home.

“You can’t understand what it is to be a parent until you are one,” said Taveras, who has a two-year-old daughter. “But I believe most parents want what is best for their child."

The pilot program involves 75 families from Early Head Start programs. The families, with children up to 3 years old, receive a conversation recorder -- a "word pedometer" -- that calculates how many words the child hears on a daily basis. The project is a collaboration between Brown University researchers, the LENA Research Foundation and community groups.

While children of high-income families hear up to 20,000 words a day, children from low socio-economic status families hear significantly less, some as few as 600 child-directed words.

Based on these results, parents are then coached by trained home visitors on how they can boost their child’s vocabulary through various techniques, like talking aloud about their day. Taking into consideration the Latino demographic, the language-neutral program also offers free children’s books in Spanish and has a bilingual staff.

The idea for this program helped Taveras win the $5 million grand prize in Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Mayors Challenge last year. Philanthropist and former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg suggested that if the program works, it could serve as a role model for the rest of the nation.

A growing demographic

Over the last four decades, Rhode Island has seen a dramatic increase in its Hispanic population, from 5,596 in 1970 to over 130,000 in 2010. Last year, Providence County’s Latinos, largely Dominican, comprised almost 20 percent of the population. According to a recent 2007-2011 Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, 30 percent of these Latino families lived in households with incomes below the poverty level.

Latinos represent 63 percent of public school students in Providence. Last year, a report released by the Latino Policy Institute at Roger Williams University found that Rhode Island has some of the worst achievement gaps between Latino and white students in the country. While the gaps seem to be tied to ethnicity, recent national studies show that income level has the greater impact on educational achievement.

a report released by the Latino Policy Institute at Roger Williams University found that Rhode Island has some of the worst achievement gaps between Latino and white students in the country

Not everyone is convinced that the program is the best way to tackle the problem of making children fluent in reading by the third grade. Stephen Krashen, a linguist and professor emeritus at the University of Southern California, says that "coaching" can backfire, turning parents into vocabulary teachers and harming parent-child communication.

“The best way, without question, is encouraging read-alouds -- very little coaching is required,” Krashen says. He adds that the Reach Out and Read program, which uses medical providers to encourage families to read to their children, is an example of a program that “costs nearly nothing and has profound effects on children's vocabulary.”

Taveras says that all programs are important for their different approaches, and that what he loves about Providence Talks is that even if parents can’t read to their kids, they learn that conversation is a very important and powerful tool for developing a child’s mind.

“I knew that reading to my child was important, but I didn’t know how important it is to just talk to my daughter about things we see and do, like teaching her about colors and shapes by describing them at the store or at home,” he explains.

Eighty-one percent of Latino students are not proficient readers, according to a recent study on U.S. early reading proficiency. The Annie E. Casey Foundation study also found that the reading gap between low- and high-income students has increased by 20 percent over the last 10 years.

Providing specific tools and guidance, says Taveras, can be one way of harnessing parents' hopes that their children achieve despite a lack of resources.

"They want to help their child and provide great opportunities for them,” he says. He hopes the "word pedometer" is a step in the right direction.