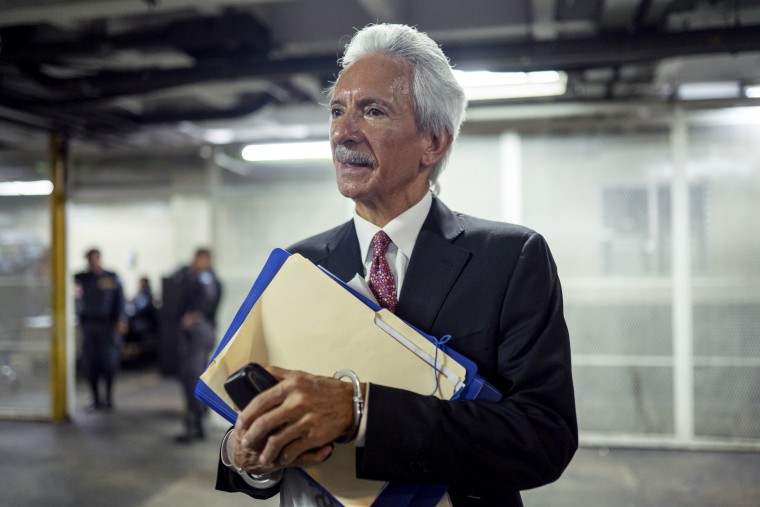

It's been nearly a year since prominent Guatemalan journalist José Rubén Zamora, the founder of the independent investigative newspaper El Periódico, was imprisoned in his homeland in connection with a case decried by human rights activists and groups as a political persecution seeking to undermine democracy and freedom of expression.

"The State of Guatemala and more specifically President Alejandro Giammattei has had my father kidnapped for 343 days," José Carlos Zamora, a journalist and longtime media executive in the U.S., said in Spanish. "He spends 23 hours a day locked in solitary confinement, with just one hour of sun."

Guatemalan authorities arrested José Rubén, 66, last July on accusations of money laundering, blackmail and influence peddling. The blackmail and influence peddling charges were dismissed during the monthslong court battle, but he was sentenced to six years in prison last month in the money laundering case. The sentence was far lower than the 40-year sentence requested by the attorney general’s office.

In an interview, José Carlos detailed how "all of my father's rights were violated" throughout the process, the family's plan to appeal and how his father's case connects to Guatemala's presidential election.

The charges stem from asking a friend to deposit a $38,000 donation to keep the newspaper going rather than depositing it himself. José Rubén has said he did so because the donor did not want to be identified supporting El Periódico in the sights of Giammattei.

According to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, José Rubén faced "violations of due process guarantees, the prolonged use of pretrial detention, and serious limitations to his right to defense" since his arrest on July 29, 2022. He even went through as many as 10 attorneys in nine months because of harassment and threats.

The court also did not admit evidence or witnesses José Rubén’s counsel presented at the trial's evidence hearing, the commission found. His son said he believes the excluded evidence would have helped his father clear the remaining money laundering charge for which he was sentenced, because "it showed where all of the money actually came from."

José Carlos said what he called his father's persecution is the result of decades of fine-tuning tactics from what he calls "the manual of repression," which has long resulted in the harassment, persecution and, in some extreme cases, the killings of journalists working to uncover wrongdoing and government corruption.

In more recent years, Guatemala has leveraged the power of government offices, such as the treasury department, to attack the credibility of news organizations and journalist through "fiscal terrorism," said José Carlos, who is the chief communications officer at Exile Content. "It's effective because it requires having auditors investigate for months and it ultimately serves to distract you from what you're working on."

José Rubén has overseen dozens of investigations into corruption during his leadership at El Periódico since it was founded in 1996 — making him and his family vulnerable to government-run defamation campaigns, car explosions, illegal raids, kidnappings, death threats and assassination attempts.

That did not stop José Rubén from publishing stories in 2020 pointing to 144 cases of corruption during Giammattei’s first 144 weeks in office.

Some of the most scandalous involved corruption in the purchase of Covid-19 vaccines and bribery of Guatemalan officials doing business with Russian miners, José Carlos said. "These investigations ultimately caused the state to fabricate a case against my father."

Since then, attacks on José Rubén and El Periódico have been so fierce that the newspaper was forced to shut down its print edition in December and its online operation earlier this year, José Carlos said.

Shutting down the newspaper was one of the goals of the Guatemalan government, as well as punishing his father for exposing Giammattei's regime, José Carlos said.

"They were also looking to send a message to all Guatemalans journalists," he said. "If they can go after my father, they can go after any of them. That is ultimately a very strong message and an ever-stronger attack."

As of last month, at least 20 journalists had been forced to flee the country in recent years, according to the Guatemalan Association of Journalists.

For José Carlos, that "has been a very open political persecution of press freedom that has deprived Guatemalans of being well-informed and demand to have decent leaders.”

José Carlos said the Guatemalan government was racing to convict his father right before the presidential election's first round of voting on June 25, because Giammatei and his administration "have been losing power" at a time when his justice system has been criticized for backsliding on democratic principles and weaponizing prosecutors and courts to pursue perceived enemies.

Rafael Curruchiche, the prosecutor in José Rubén's case, is even on the U.S. State Department's list of "corrupt and undemocratic actors."

While the U.S and leaders in other democratic nations have called out the Guatemalan government in connection with José Rubén's case, José Carlos said more can be done, such as direct sanctions to such people and the nation.

Considering the U.S. and Guatemala have been looking to work together to curb immigration to the U.S.-Mexico border, the U.S.’s not being tougher on the country's anti-democratic issues sends mixed messages to the Guatemalan government, José Carlos said.

"Corruption has been robbing Guatemalans of their hope, and it drives them to migrate," he said, adding that while both countries can invest in armies to stop migration, it still doesn't solve the core issue pushing people out of their homeland.

As José Rubén's family plans to appeal the case on due process grounds, José Carlos is optimistic that a new regime won't harm his father's shot at freedom.

"I don't think the next administration wants to inherit this," he said, adding that new candidates have worked to position themselves as the solution to restore Guatemala's eroding democracy.

If the evidence and testimony excluded from the previous trial are included in the appeal, the case against his father "will fall apart," José Carlos said. He hopes that will happen in a Guatemalan court. If it does not, the family is ready to go to international court.

"He is innocent," José Carlos said of his father. "This case was fabricated, and he will eventually be absolved and freed."