NEW YORK, NY -- As a middle-aged HIV-positive gay Latino, I’m happy to report that those identities now co-exist peacefully. I often still look at the world through only one lens at a time, but I now more often merge all those views for greater insight. That accomplishment was not easy for me to achieve, but I’m certain that middle age was the key ingredient.

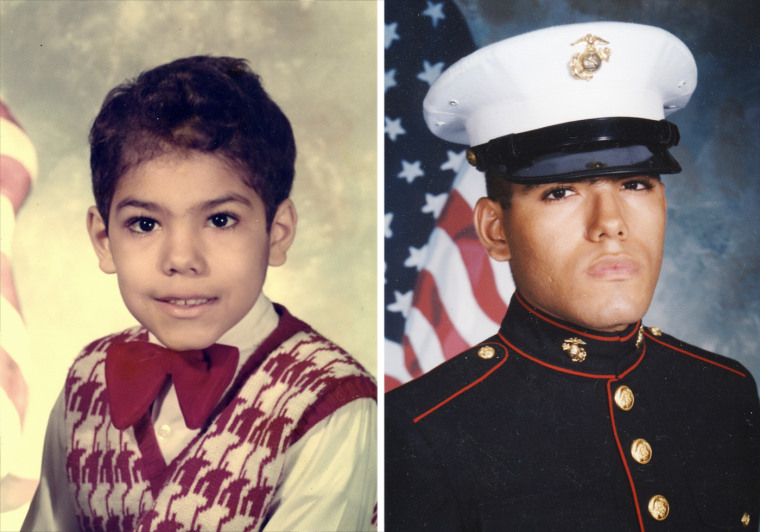

Realizing that I’m probably more than half done brought me clarity. Middle age tends to do that to people, so I claim no special prize for that realization. Nonetheless, I’m grateful for my current clarity because my life previously was quite fuzzy. Since I was diagnosed with HIV in 1992 at the age of 22 while still in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, I was convinced that I would die before 30.

My fears of an early death weren’t unwarranted. When I was diagnosed, AIDS-related deaths were increasing and no effective HIV treatment existed. My fears only increased in 1994 after my boyfriend who transmitted the virus to me died. Effective treatment arrived in 1996, but I still didn’t believe that I would see the new millennium.

Much of my pessimism during the ’90s was fueled by major depression, which in no small part was the result of being closeted about both my sexual orientation and my HIV status. I told my Roman Catholic parents I was gay in 1996, but I couldn’t tell them I was living with HIV until 2008. Such was the stigma I attached to the virus.

Escaping the closet - twice - has been life saving. The things we disclose often aren’t as terrible as we feared and the unburdening is often even more freeing than we imagined.

This is how I rationalized that decision: I’m going to die soon anyway, so why burden them with a double whammy. I owe them an explanation about not giving them grandchildren, so I need to tell them I’m gay. That truth will be difficult enough for them, so I’m being kind by keeping them in the dark about HIV.

Over the years, as I realized I wasn’t going to die an early death, I slowly adjusted to living. I started allowing myself to emotionally invest in long-term relationships. I took my work more seriously, since I had to think about retirement. I went to graduate school, investing in my future work life. I grew more comfortable in my skin.

When I saw my personal growth of over a decade being limited by remaining closeted about my HIV status, I came out again. The second time was surprisingly easier. That’s not to say that it was easy. A truth that for me was very old news was breaking news for my parents. Only learning about HIV over time would ease their concerns.

So it is with coming out. The things we disclose often aren’t as terrible as we feared and the unburdening is often even more freeing than we imagined. Being a first-generation Cuban American, I feared my parents would not only reject me, but also regret the sacrifices they made for me. After much turmoil, those fears have disappeared.

Much before I knew the meaning of the word “gay,” I knew that I was gay. I never was closeted to myself growing up, but my conservative upbringing made me believe that I had to stay closeted to the rest of the world. I internalized that homophobia to the extent of even believing that I could turn myself straight. Of course, that didn’t happen.

What did change was my understanding of the world. I’m astounded at how quickly public opinion has progressed in the United States and increasingly around the globe. We've gone from widespread hatred to majority acceptance of equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. I never thought that would happen in my lifetime.

To be sure, being LGBT in too many places remains a death sentence, and violence, harassment and discrimination for simply being LGBT remains a reality. Sadly, such indignities remain true not only in developing countries, but also in developed countries. Being LGBT remains dangerous, despite progress.

While danger may lurk, to paraphrase the saying, honesty has been the best policy for me. Escaping the closet, twice, has been life saving. HIV treatment alone wasn’t going to do the trick. Being honest about who I am lifted my major depression, which allowed me to be adherent to my HIV treatment. Pills don’t work if you don’t take them.

Aging with HIV has brought not only the delight of being alive, but also the aches and pains we all share. Aging as a gay man has proven to be less traumatic than I thought it would be, but being in a long-term relationship has helped. Aging as a Latino has been exactly as I thought it would be—our zest for living has made it a lot of fun.

Seeing the world through each of those lenses gives me important insights, but it’s only when I overlap all those perspectives that I get a three-dimensional view. As any movie fan will tell you, at least with modern films, there is nothing like seeing things in 3D.

Oriol R. Gutierrez, Jr. is editor-in-chief of POZ magazine and POZ.com, a national, award-winning magazine and website for people living with, and affected by, HIV/AIDS. He co-founded LGNY Latino, the first bilingual Spanish/English LGBT U.S. periodical and is a former vice president of the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association.