Growing up, I was used to sitting through my dad’s long stories, whether or not I wanted to hear them. At the dinner table or in the car, my brothers and I listened to my father tell us about his childhood in El Paso, about serving in the Army, about meeting Robert F. Kennedy. My usual response was to zone out. I had heard all of these stories a million times.

There was one story, however, that intrigued me. The only problem was that my father didn’t like telling it.

From the few times I heard it, the story went something like this: It was a hot day in August when my father left work early to attend a “Peace March” in East Los Angeles. Billed as The National Chicano Moratorium, it was a protest against the number of Mexican-Americans dying in Vietnam.

This alone piqued my interest, because my dad never called himself a Chicano. He was a straight-arrow striver. He was a bank manager. It was hard to imagine him at a protest, especially among the kind of people he usually referred to as “militants.”

But that day was different, my dad said. The anger about the Vietnam War was so great that everyone seemed to turn out for the march, including many of his co-workers and friends. There were all sorts of people there, from children to senior citizens, even a wedding party. The march wound its way through East L.A., and then ended with a rally in a park. As he told it, my father was under the shade of a tree, listening to the speeches. All of a sudden he heard a pop-pop-pop sound and the crowd began to disperse in panic.

I gotta get out of here, my dad thought. He darted down an alley, where he was confronted by Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department officers charging at him with guns drawn. Reversing course, my father ran around the corner, only to be blocked by more officers wielding tear gas. As the largely peaceful gathering degenerated into a melee, my father made a break through a side street and walked home. He was so shell-shocked that he forgot he had driven to work.

As a kid, this was the most memorable part of the story: Dad forgot his car! It was years before I understood that my father was on the scene for one of the pivotal days of the Mexican-American civil rights movement. It was August 29, 1970, 44 years ago today. That “Peace March” constituted the largest political assembly of Mexican-Americans to date.

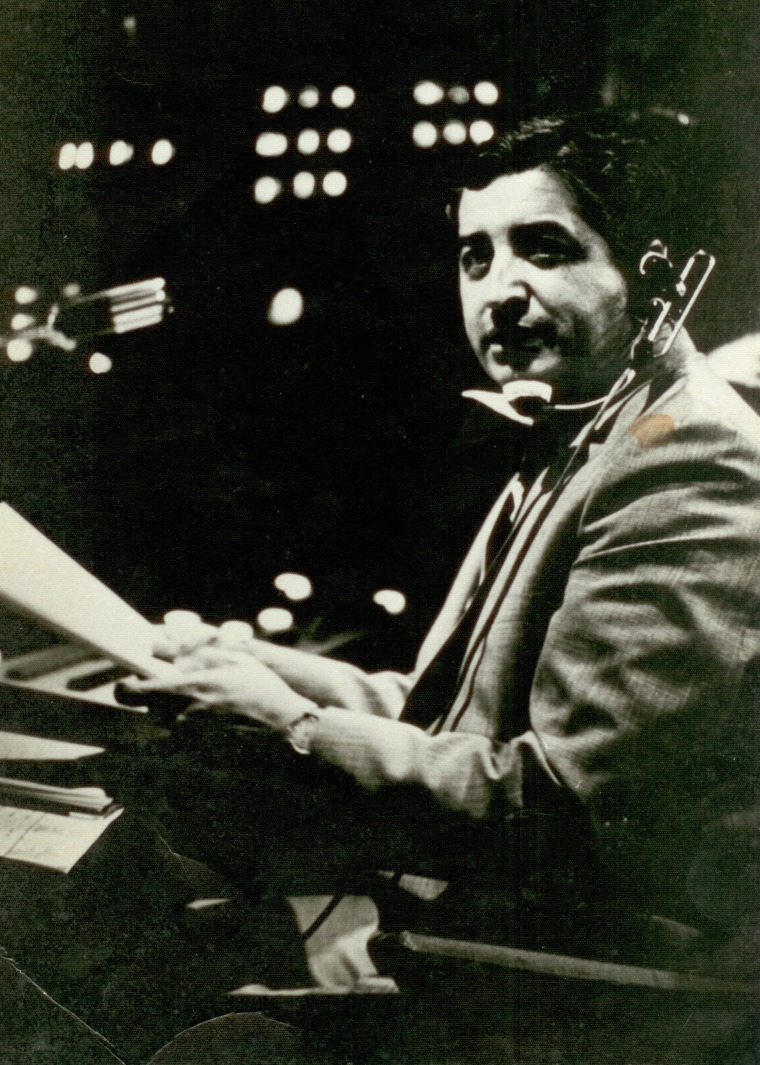

By the end of that day, scores of marchers had been arrested and three people were dead. Among them was Ruben Salazar, a pioneering Hispanic journalist who had been a foreign correspondent for the Los Angeles Times but later distinguished himself for his weekly columns on the issues surrounding the Chicano community. He was relaxing in a bar when he was shot in the head by a tear gas projectile fired by an L.A. County sheriff’s deputy. Salazar was 42.

Back then, Salazar’s death shocked my family. My parents, aunts, and uncles all trusted the government. My relatives were second-generation Americans who saw themselves as fully part of American society. The killing of Salazar suggested to them, sadly, that maybe they were not.

As a kid, this was the most memorable part of the story: Dad forgot his car! It was years before I understood that my father was on the scene for one of the pivotal days of the Mexican-American civil rights movement.

Because of my father’s connection to that seminal event, I’ve thought a lot about Salazar over the years. As an adult, I learned that he died under mysterious circumstances. Although a coroner’s inquest ruled the killing a homicide, the deputy who killed Salazar was never charged (It took the L.A. Sheriff’s Department until 2012 to publicly release its records relating to the killing). When I wrote a story on a documentary about Salazar earlier this year, I discovered that there are still unanswered questions about his death.

Salazar is important to me because he was not just the most prominent Latino journalist of his day – he was the only prominent Latino journalist of his day. He was a trailblazer for all the Latino journalists who have followed in his footsteps (his death led to the formation of the California Chicano News Media Association, which paved the way for the National Association of Hispanic Journalists). As I watch the news unfolding from Ferguson, Missouri, I can’t help but think that Salazar’s reporting on law enforcement tactics in minority communities remains as relevant now as ever.

Not so long ago, my father brought up that summer day when he attended a peace march that ended in tragedy. While I was surprised that he mentioned it, I was glad to hear the story again. It reminded me that I shouldn’t limit myself to reading about the struggle for social justice; in a small way, my dad had been a part of it.

So maybe my father finally understood the importance of talking about the stories that make us uncomfortable. Or maybe I was finally a more open and mature listener. Either way, I thought, Ruben Salazar would be proud.