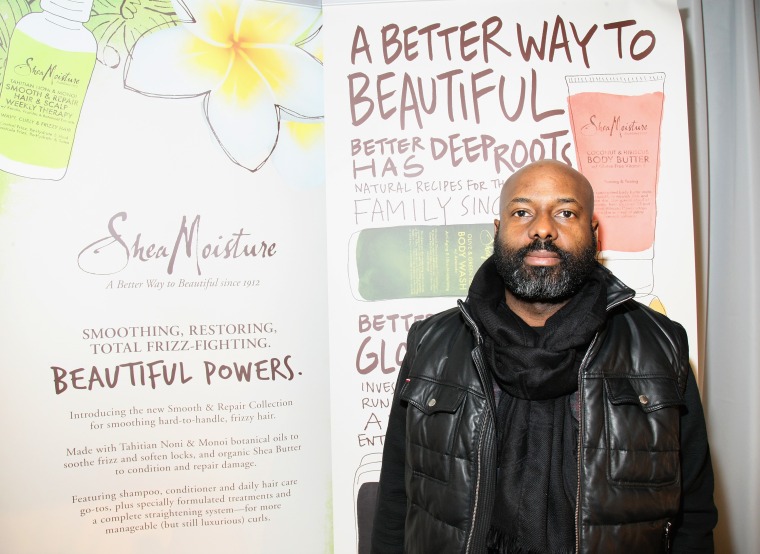

Being a Black-owned business in the beauty industry presents a unique set of challenges. Through the years, we’ve received questions and judgments about our products and our business that I’m pretty sure few, if any, white-owned businesses have ever had to answer – like “Since you’re Black, your products are just for Black people, right?” or “We don’t really have a place in our store for a hip-hop beauty brand.” Now, I’ve loved rap music since the Sugar Hill Gang, Slick Rick and Doug E. Fresh, but I couldn’t understand how personal care and beauty products made from organic and natural ingredients that simply serve people according to their hair or skin care need – whether curly, coily, wavy, straight, damaged, dry, oily or other – could be labeled as “hip-hop.” Then, it hit me. They weren’t seeing the products. They were only seeing me.

You could say I was born into entrepreneurship. My grandmother, who was from Sierra Leone, was left to raise four children in the 1940s in a rural village in West Africa after becoming a young widow. To support her family, she made natural skin and hair care preparations and sold them primarily to missionaries and villagers. Through both her personal experiences and her experiences as a village merchant, she learned – and taught me early on – that with an efficacious natural product, the consumer is not to be typecast. This is the legacy of my family and the brands we build at Sundial Brands (maker of SheaMoisture, Nubian Heritage and Madam C.J. Walker Beauty Culture).

RELATED: Analysis: Where Do We Go From Here: America After Obama

I was born and raised in Liberia and came to America to attend college. When I graduated in 1991, Liberia was in a civil war, and I was unable to return home. It was then that I started Sundial with my college roommate – Nyema Tubman, and my mother – Mary Dennis. We began making soaps developed from my grandmother’s recipes in our Queens apartment and started selling them on the streets of New York City to survive. As our company grew and we began growing our family stateside – with heritages ranging from Liberian and Sierra Leonean to Irish, Indian, Swedish, Filipino, German and beyond, our different cultural influences and walks of life helped us even better understand the criticality of an inclusive point of view. In a sense, we are a “united nation” and a “national urban league” of our own, and that has impacted how we view the world, how we view business – and perhaps most importantly, how we view our purpose in both.

We started our company out of a need to survive, but we’ve built it based on a mission not only to help others survive, but to prosper. In fact, we view ourselves as a mission with a business, rather than a business with a mission. Because of that, our purpose – to empower people to live more beautiful lives – sits at the center of everything we do as company and compels us to keep community at our core. This spirit of purpose and empowering those around us led to our purpose-driven business model called Community Commerce, which equips underserved people and communities with access to the opportunities and resources that enable them to create lasting value for themselves and others. It results in an ability to build stronger, self-sustaining communities and enterprises.

This has been our business model since we began in Harlem 25 years ago providing high quality goods that were not previously available to underserved store owners and other street vendors. As our business has grown, so have our Community Commerce focus and impact. For example, through our women’s empowerment pillars of Entrepreneurship, Education & Equity – or as we call it, WE3, Community Commerce now invests in underserved women in each of these areas via supplier partnerships, fellowships, scholarships, mentorships and other resources.

RELATED: Are African-Americans Locked Out? State of Black America Report

In addition, since Shea butter is central to all our products, we ethically source our Shea butter from 14 women’s cooperatives in Northern Ghana and invest in more than 6,500 women entrepreneurs. When we invest in these cooperatives, we don’t just buy their products — we help them develop self-sustaining businesses. An ethical wage premium is paid to these enterprising women, and we aid in monitoring practices to ensure that the efficiency, health, profitability and quality of life is elevated for members of the co-ops. We’ve also made infrastructure investments in the co-ops to bring piped, fresh water for the first time (enabling the girls to go to school rather than be tasked with fetching water all day) and in warehouse storage (so the women can harvest the Shea nuts longer and not be forced to accept basement “end of season” pricing from large conglomerates). Whether across our ingredient supply chain – in Ghana for Shea butter and coconut oil, Jamaica for black castor oil, Morocco for argan oil, or Turkey for rose oil and rose water - or in the United States with our domestic efforts under WE3, the women we work with become our partners. With their rise in skill and income, they experience greater health, access to education and opportunity and the benefits of financial freedom. From sourcing to shelf, we are key to each other’s success, and this model for conducting community needs assessments can be scaled across cities, countries and continents.

Making an impact isn’t just how – but also why – we do business. As such, part of our vision has also always been to build a business and a business model that other minority-owned or under-resourced businesses could be inspired by, learn from and expand upon. We began Sundial Brands as young entrepreneurs, and as we move forward towards our goal of becoming the number one global family company serving our communities in a way that is aligned with their needs and our core values, we will always be entrepreneurs. We will always have a unique understanding of and appreciation for the challenges, opportunities, setbacks and successes that come along with it.

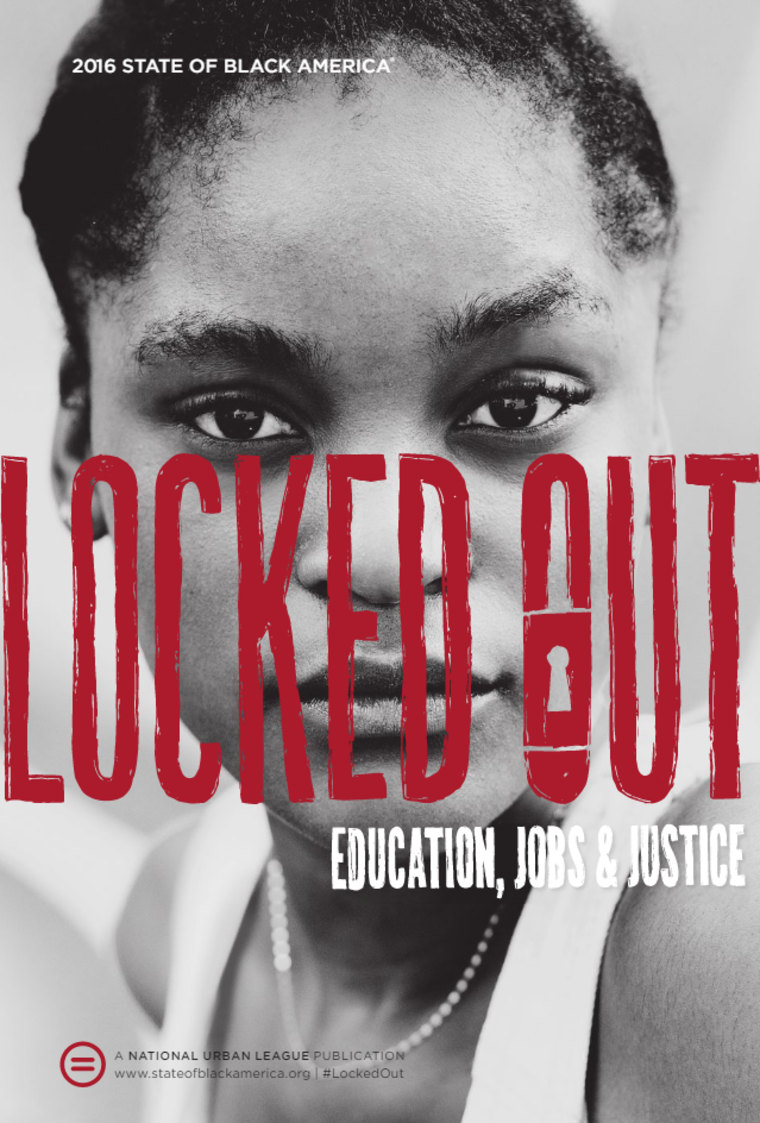

This essay is part of the 2016 State of Black America Report. The rest can be found at stateofblackamerica.org.