In one of the two essays that make up “The Fire Next Time” — James Baldwin’s classic book, published in 1963, that examines the roles of race and religion in America — the author pens a letter to his nephew, also named James. Baldwin writes of the absence of his mother, Berdis Baldwin, from his fellow Americans’ consciousness: “Your countrymen don’t know that she exists ... though she has been working for them all their lives,” he writes.

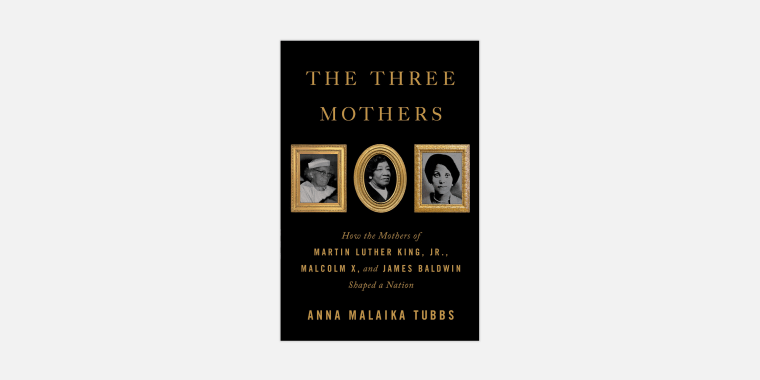

That absence and the absences of two other Black mothers are the basis of author Anna Malaika Tubbs’ debut book, “The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation,” published last month by Flatiron Books.

The book, Tubbs writes, “fights that erasure” of Alberta King, Louise Little and Berdis Baldwin — three Black women whose life experiences, passions, and intellects were crucial in shaping their sons’ revolutionary spirits.

“These men became symbols of resistance by following their mothers’ leads,” she writes.

Tubbs researched the book for three years as part of her studies for a Ph.D. in sociology at the University of Cambridge, where she received the competitive Gates Cambridge scholarship and earned a master's degree in gender studies.

Tubbs said part of her motivation was that while all three men wrote and spoke about their mothers’ influence on their activism, scholars have largely ignored examining the women’s lives and contributions in favor of the men’s fathers’ — an omission that Tubbs sees as a product of patriarchy.

“I think there’s something interesting that happens in the gender binary, where we assume that men are influenced by their fathers, so scholars go looking for the father relationship, whether the father was present or not,” Tubbs said. “With James Baldwin and Malcolm X and MLK Jr., everybody knows something about their dads — whether they were good fathers or not — and they don’t know about the women who were there from the very beginning.”

Relying on interviews with family members of the women, their sons’ writings and speeches and archival documents, Tubbs fills the gaps in the archive, unearthing what she calls “beautiful intersections” between the women’s lives and those of their sons. Among them are that Louise, Berdis and Alberta “were all born within six years of each other, and their famous sons were all born within five years of each other.”

That allowed Tubbs to place their lives within the broader historical contexts in which they unfolded — the Great Depression, the Great Migration and the Harlem Renaissance. Each of the women also harbored a love for language — in spoken, written and musical form — that they passed on to their sons.

Other convergences were tragic: All three women outlived their sons; Malcolm X, King and, later, Alberta King all died by assassination. The three men had planned to meet in person at a group interview scheduled for just two days after Malcolm X was killed in 1965.

Despite the similarities, it is the distinct arcs of the women’s lives that Tubbs foregrounds in her book: how Little’s childhood on the Caribbean island of Grenada — a country rich with histories of resistance to British and French colonization — in a house led by her grandmother Mary Jane instilled in her a “radical feminist energy” that she maintained throughout her life. Alberta King followed in her parents’ footsteps by leading her faith community at Atlanta’s historic Ebenezer Baptist Church. Baldwin channeled her love of writing into the lifelong letters she penned for family members.

To Tubbs, the personal stories illustrate larger political truths about the variety of Black women’s lived experiences.

“It’s part of reclaiming our humanity, by saying, no, we’re not all the same, we can’t be reduced into these categories, we’re incredibly diverse, and that’s one of the strengths of our community and something that we want to see more of: accurate representations of our experiences,” she said.

Alongside the stories of the women’s lives, Tubbs incorporates works of Black feminist theory — by scholars including Audre Lorde, Melissa Harris-Perry, Brittney Cooper and Patricia Hill Collins — to analyze how the women resisted racist and sexist dehumanization and stereotyping.

Part of that resistance, Tubbs argues, manifested through what she calls “the revolutionary power of their motherhood,” which relied on cultivating self-love in their Black sons and instilling in them senses of possibility and responsibility to create positive change in the world and reject anti-Black racism. Bringing a Black feminist lens to the project allowed Tubbs to theorize the women’s experiences of motherhood as both labor and liberation — in stark contrast to how some white feminist theorists have argued for understanding motherhood.

“So many white feminist scholars have really targeted mothering as a place where white patriarchy is reproduced, but Black mothers approach it very differently. ... We actually see motherhood as an opportunity for liberatory practices to be passed from body to body, from mind to mind,” she said. “That’s really what I see in terms of Alberta, Berdis and Louise, and that’s how they created these change-makers in the world.”

Tubbs’ work has particular relevance for Black mothers in the U.S., who have been among those hit hardest by unemployment caused by the coronavirus pandemic. And within the past year, some Black mothers in the U.S. — including Tamika Palmer, the mother of Breonna Taylor, and Wanda Cooper, the mother of Ahmaud Arbery — have joined the ranks of other Black mothers grieving for their children after their killings by police and white people.

For Tubbs, bringing these realities to the forefront is only the first step toward change; the reader's work, she said, lies in confronting them.

“It’s also a call to action, to say: Stop admiring us, stop studying us — turn those things into change,” she said. “In terms of the fear we feel for our children and ourselves, that’s very current, and we shouldn’t have to deal with that and hold that burden on our own.”