ITTA BENA, Miss. — Shawn Robinson, 50, has a view from his front stoop that he often finds more interesting than what's on TV. From the doorway of his building on the edge of Itta Bena’s town square, Robinson can see people come and go from this struggling Mississippi Delta town's only no-fee or low-fee ATM.

Robinson has seen women stand in front of it and start to cry. On a few occasions he’s heard church folks use blue language or seen people smack the brick wall around the ATM. (The machine itself is too precious to ding.) The most frequent reaction: variations on a sigh.

In Itta Bena, population 1,828 and likely declining, the four other ATMs sit inside gas stations and charge $5.25 to $7.50 per transaction. So, the demand for the most basic financial services at an affordable rate is such that on one or sometimes two days a week, Hope’s ATM runs out of money.

People need cash in Itta Bena. Between the boarded-up dry cleaner and the fraying remains of an American Legion hall, just one store in the center of town sells food — almost exclusively in boxes, cans or bags — and it does not take credit cards. For those without their own vehicle, $20 cash is the going rate for rides to and from the next town and its hospital, shops, banks and full-service grocery stores. In Itta Bena, money-sharing apps such as Venmo haven’t yet caught on.

“You can’t do much without money, just like anywhere else,” said Robinson, a former factory worker who has been living on disability payments since the late 1990s after he fractured his pelvis in a car accident, leaving him with an atrophied and shortened leg. “But here, you have a hard time getting money even if you have some, can’t find a place to spend money if you need to and basically have to figure out a way to get somewhere else to take care of almost anything. It’s a little bit like ants in one of those glass boxes: You see people busy, just going nowhere.”

What Robinson is watching isn’t simply the most active spot at the center of a small, struggling town. Robinson has an unavoidable view of an economic problem so fundamental that even those experiencing its effects may not recognize its cause. He is standing in one of the 6,008 places where the nation’s banks have closed branches from 2008 to 2016.

Itta Bena is a banking desert, a place where traditional banks have completely disappeared.

The seen and unseen role of banks

Banks — where they are, who they lend to and on what conditions — are a key lever in the American economy. Yet branches are closing at a rapid pace, with more than 3,800 shuttering since 2017. Most of those branches closed in overwhelmingly nonwhite urban neighborhoods in cities like Baltimore, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit and Las Vegas, but rural communities have also struggled. In some, like Itta Bena, the one or two banks that used to exist are gone.

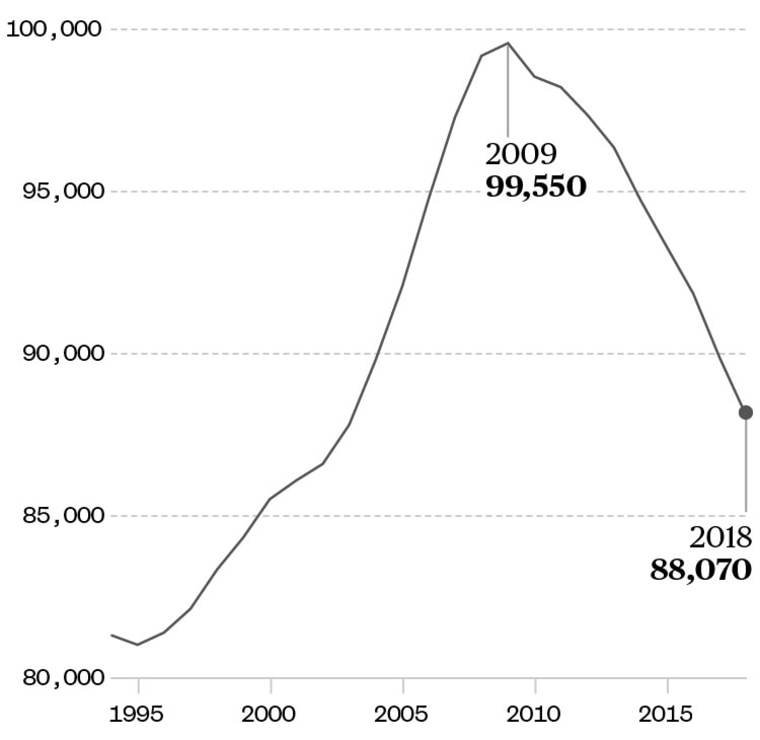

The rise and fall of bank branches

The number of branches in the U.S. peaked in 2009, during the Great Recession.

“It is one of those things people see but don’t see, know but oftentimes don’t understand to be a community-altering thing,” said Bill Bynum, CEO of Hope Credit Union, which he helped found in 1995 and now has branches in 22 communities.

When banks went on their closing spree, they did so in ways that created 86 new banking deserts. In rural areas, these are population clusters where no bank exists within 10 miles. Some Americans may hear that and shrug: What’s the value of a bank branch when accounts can be opened, funded and managed online?

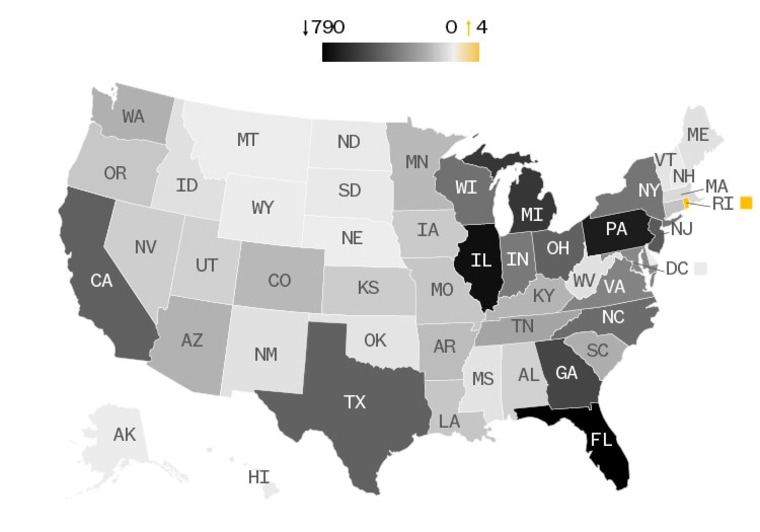

Disappearing banks

Every state except Rhode Island saw the number of bank branches fall from 2008 to 2018.

For starters, a 2017 survey found that more than a third of Americans went into a bank branch 10 or more times in the previous year. About 85 percent did so at least once. And there are consequences when a bank branch closes. Researchers have found more people with no bank accounts at all in places with less access to local bank branches.

What’s more, lending — that engine of the American economy — tends to decline in areas where bank branches have closed, according to a 2014 study by an economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Business lending, a process that is often rooted in relationships with bank staff, tends to decline for about six years after a bank closes and then remains lower than it was previously, even if another bank arrives. Mortgage lending tends to drop off for about three years. The effects of a bank closure stretch about 8 miles from a shuttered branch.

“The bank branch is to local economies what the debit card is to your wallet — a key point of contact to the financial system and the way a large part of the population accesses non-predatory financial services,” said Jesse Van Tol, CEO of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, an association of community development organizations.

“Apps are great,” Van Tol continued. “Nobody denies that. But there are, believe it or not, some important things that can’t be accomplished on your cellphone.”

The ripple effects of a bank closure

Itta Bena’s last bank branch closed in 2015.

It could hardly have happened to a more distressed community. The population was shrinking, the poverty rate sat at around 40 percent, five-year average unemployment reached 31.4 percent and median household income was $21,792.

Regions Bank, part of the Birmingham, Alabama-based Regions Financial Corporation, which operates banks around the Deep South and Midwest, had occupied the one-story beige building across from the Itta Bena town square for at least a decade. The bank decided to close up shop for the same reasons banks are closing branches everywhere, a bank spokesperson said.

The cost of operating a branch is at least $200,000 a year, including rent, salaries, power and building upkeep, according to the bank services company ARCA. And foot traffic, transactions and other activity weren’t keeping pace, the bank spokesperson said.

By the reasoning of much of the business press, “bank consolidation” is a no-brainer. Between bank apps and credit unions, people up and down the income ladder can access non-predatory financial services. Criticizing banks for closing branches and concentrating those closures in low-income communities is “misguided,” a Forbes contributor wrote in March. The St. Louis division of the Federal Reserve has said bank closures began in response to the financial crisis but can today be attributed, in part, to customer migration online and bank mergers.

Regions Bank officials are quick to point out that the bank did not simply lock the door. It donated the physical building and associated infrastructure — including that ATM where Robinson likes to people-watch — to Hope Credit Union and helped customers who wanted to move accounts there to transition. In exchange, the bank received credit under a federal program that encourages federally insured banks to lend in economically distressed areas.

As a nonprofit and member-owned credit union, Hope can offer many things banks don’t — including short-term loans of $500 — but it can’t match a bank in lending power, Bynum said. Hope, for example, generally can’t lend out the money for multimillion-dollar projects alone, so it has worked with larger institutions on projects such as renovating deteriorating apartment buildings. Hope’s No. 1 product in Itta Bena is auto loans. Access to affordable financial services, right there in town, is important enough that 690 people — the equivalent of 40 percent of Itta Bena’s population — have joined Hope Credit Union.

When a bank branch closes, the decline in business lending and competition for customers can have a significant impact on a small town. It means less money is available to start or expand businesses and pay workers who will spend at least some of that money locally. And it creates a cycle: More unemployed people, and more people with limited incomes, make other businesses uninterested in the town.

But that probably doesn’t explain all that ails Itta Bena’s economy.

Itta Bena has been battered by forces as large as globalization, de-industrialization and a rising information economy, along with forces as local as white flight, a shrinking tax base and growing infrastructure needs.

The most recent business anyone can remember opening near the center of town emerged more than four years ago. It’s a gas station stripped to its minimal parts. It has a single pump, accepting only credit and debit cards. There’s no clerk, no shop selling anything.

“I really don’t know why that’s here, except to collect electronic money,” said Minnie Pearl Journey, 60, a longtime resident. “I don’t know that it’s doing too much for Itta Bena, if you ask me.”

Itta Bena’s ghost map

Itta Bena began in the 1840s when Benjamin Grubb Humphreys, a Mississippi plantation owner and later a Confederate general and post-war governor, rode a river into what had, just a decade earlier, been Choctaw tribal land. Humphreys set slaves to work clearing the forest and building a grand home. He dubbed the several hundred acre plantation Itta Bena, a Choctaw term for “home in the woods” or “camp together.”

In the decades that followed, a town grew around it, taking on the same name. The region produced so much high-quality cotton that Mississippi became the country’s chief cotton producer. By 1860, Mississippi was one of the nation’s richest states, long home to half the nation’s millionaires. All of that was made possible by the nation’s largest number of slaves.

Cotton was still a big industry in town when Journey moved there about 45 years ago. Back then, what is now a muddy lot near the jail housed the Itta Bena Compress, a cotton gin. For about 17 years, Journey worked there as a locator, classifying the quality of cotton bales and organizing them.

The long-gone cotton gin is just one place Journey can point out on a kind of ghost map, the places where key services and goods used to be sold.

There’s the pharmacy on the town square where Journey used to pick up medicine and coloring books and crayons for her three children. The drug store has been gone for about a decade, Journey said. Her children are now grown, and only one has stayed in town.

Another ghost: the giant corrugated blue metal building that once housed The Big Star grocery store. Journey shopped there a few times a week when her kids were growing up and her twin boys, it seemed, were perpetually hungry. It closed around 2009.

The town square is rimmed with buildings like this, still standing or mostly standing with the remnants of signs and logos.

What the town lacks in businesses and jobs, it does not lack in places of worship: At least 17 churches line the streets, plus there are in-home churches, where no one has put up a sign.

Itta Bena is a place small enough that Journey, at 4-foot-11, can stride almost anywhere she might want to go. But that’s not really far enough to accomplish most things.

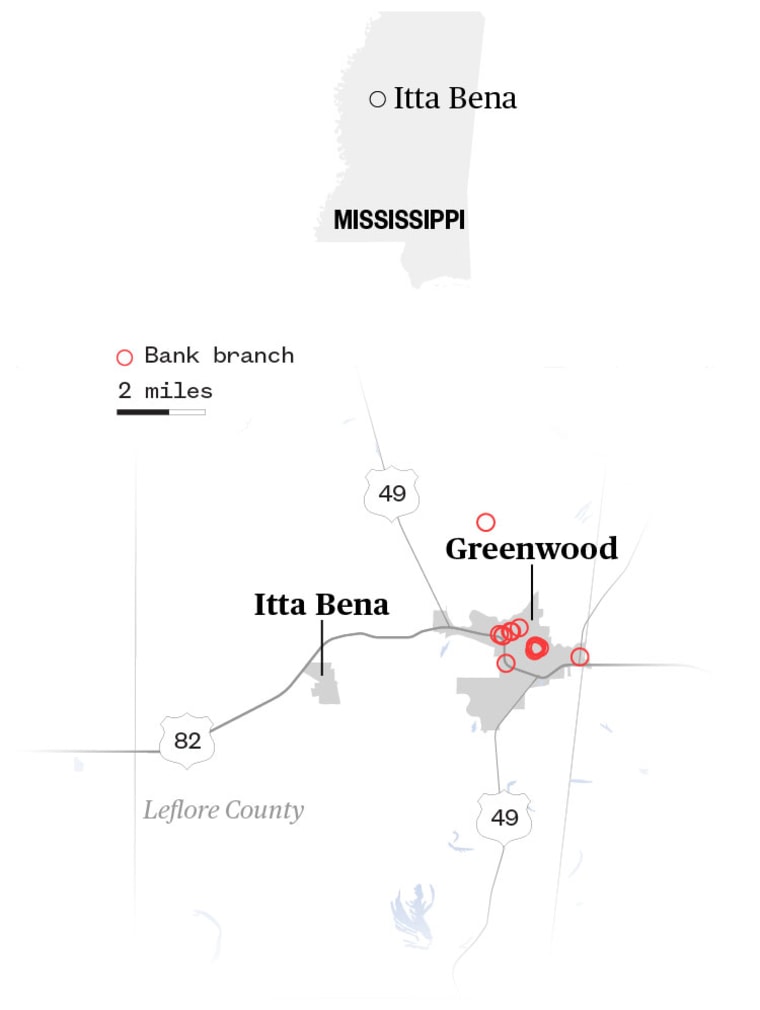

The Dollar Tree about 7 miles from the center of town sells hair and cleaning products, notebooks, snack and frozen foods and, since 2017, when Itta Bena’s former mayor petitioned the company, a small selection of fresh fruits and vegetables. But one has to go to Greenwood — 11 miles east — for a full-service grocery store, a pharmacy or a medical specialist. And to find a four-star hotel requires a 43-mile trip west to Greenville.

To get to any of those places, Journey and everyone else in town needs a car or the cash to pay for a ride. Almost half of Itta Bena residents over the age of 16 commute an average of 17 minutes, according to the census’ most recent assessment in 2017. There’s no mass transit, no Uber, no taxis. Journey has never heard of Venmo. So, for the 6 percent of residents without a car, like Journey, cash from an ATM is usually the only way to get out of town.

“Nobody, not even me, walks 13 miles,” said Journey, who left her walk-to-work job as a home health care worker in January and is living on a widow’s pension. “I mean, I really don’t see why with 1,800 peoples we can’t have nothing here, at least a grocery store. Instead, everything, just about everything left, it’s in Greenwood or really, way, way over yonder in Greenville.”

A few weeks after she stopped working, a doctor diagnosed a “bone tired” Journey with stage 2 esophageal cancer. Now, a charity organization picks her up, takes her to treatment and drives her back home.

A need for investment

In 1977, when major American cities were crumbling in the way Itta Bena is today, Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act, which required banks to lend in every community where they collected deposits. Banks weren’t asked to make unreasonably risky loans, just to apply consistent standards.

The law aimed to overcome the effects of redlining — denying affordable home loans to non-white borrowers and those living in mostly black and Latino communities. That practice created pent-up demand that private owners exploited, offering high-risk and high-cost rent-to-own homes to black buyers that set off waves of eviction and vacancy in major cities.

Some 40 years later, the Community Reinvestment Act hasn't met its full potential. It’s been credited with slowly boosting nonwhite homeownership rates, seeding investment that sometimes turned around a block or entire low-income communities and reducing vacancy, according to the Cleveland branch of the Fed. But, in the decade since the Great Recession, as bank and other corporate profits have reached new highs, banks have closed branches in poor communities while opening branches in wealthy ones. Yet, most years, 90 percent or more of banks that are evaluated received at least a “satisfactory” rating on their Community Reinvestment Act performance.

That’s led to calls from consumer and civil rights advocates for changes to the act that would increase banks’ accountability for lending to low-income people and investmenting in businesses where they live. Advocates have also sought to regulate the activity of online lenders that have no bank branches at all, because they now issue the majority of mortgages. These groups have also called for regulators to evaluate all lending institutions based on where branches are located as well as where they are collecting deposits.

Right now, when a bank closes multiple branches in a region, its Community Reinvestment Act assessment area can also change. That can allow deeper economic deterioration that never registers on regulators’ radar. For example, Regions is the only one of the 20 largest banks with branches around the Southeast that is assessed on its activity in the Mississippi Delta. The bank has a “satisfactory” rating.

“What we have is a system where opportunity is heaped on communities where money is already flowing,” said Bynum, who leads Hope. “There are people in places like the Delta with ideas, with dreams and very real needs who also need someone to invest in them.”

But banks want changes to the Community Reinvestment Act, too, including credit for a broader array of loans and charitable donations like funding a business incubator or providing financial literacy classes. And, they say, online banking means branch locations matter far less than before.

With a divided Congress, no official moves to change the law are likely. But at least two members of the Trump administration — Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Joseph Otting, head of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency — have described the law as too stringent. Late last year, Otting directed his agency to issue a set of questions for public comment that will inform any proposed rules changes.

Otting’s move has raised advocate eyebrows because before joining the administration, he served as CEO of a bank that Mnuchin co-owned, one that was accused of rushing toward foreclosure auctions in a way that affected large numbers of nonwhite and older homeowners. The bank entered a consent agreement with the Treasury department that required a list of changes.

Access is ‘vital’

In mid-February, a caravan of black SUVs zoomed onto Mississippi Valley State University's campus at the edge of Itta Bena. The man inside one of them was Jerome Powell, chairman of the Federal Reserve, making the first visit by a sitting Fed chair to the Mississippi Delta.

On stage at a Hope conference for community redevelopment, Powell said policymakers should pursue “revisions to the CRA” that “more effectively encourage banks to seek opportunities in underserved areas.” He supported incentives for banks to do so.

“Access to safe and affordable financial services is vital, especially among families with limited wealth,” Powell said.

Later on the day of Powell’s visit, on the perimeter of the town square, the sun was setting and Robinson’s thoughts turned to the philosophical. Robinson has chopped cotton, worked in a slaughterhouse and made picture frames in a factory. A life of observing others in motion is not something he anticipated.

“There are people who have it good but most of them don’t know what they’ve got,” Robinson said. “I wish I could be one of them. But in a town like this, you understand that there is only so much control one man, one town, has really got.”